The Rape of Europa (39 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

The museum directors, meeting in New York on what should have been the last festive weekend before Christmas, were fully aware of the dangers of panic; indeed, one of the main purposes of their assembly was to prepare a press release to calm hovering reporters expecting to hear that every major museum in the country would instantly be closed and stripped bare.

6

With visions of London’s blitz in their minds, the primary worry of the museum authorities was air-raid damage. In this day of remote-controlled nuclear weapons the 1941 discussion seems to emanate from a different world, but the images shown to the group in a slide show prepared by Agnes Mongan of Harvard’s Fogg Museum were all too real—the walls of the Grande Galerie of the Louvre full of empty frames, the bombed-out Tate Gallery with three acres of skylights lying shattered on its floors, and the nave of Canterbury Cathedral filled with tons of earth to absorb the shock of explosions.

Many of their own institutions had hastily ordered protective actions not always the best for their works of art: at the Museum of Modern Art the major paintings on the third floor were taken down every night, put in a sandbagged storeroom in the center of the floor, and rehung every morning before the public arrived.

7

In all the museums millions of candles were ordered in preparation for power failures, fire crews were on duty around the clock, nursing stations were set up, and first-aid supplies were distributed along with gas masks. Building engineers and maintenance crews basked in unaccustomed board-room limelight. There was much solemn practical advice: “Gather up shattered fragments and wrap in cloth marked with collection number,” advised one memo. “Two men should hold the picture while a third cuts the wire” and “Haste should be avoided except where it is necessary to remove works of art from immediate danger” confided another.

Engineers at the National Gallery informed the administrator, after study, that the Gallery’s roof would not be suitable for an antiaircraft gun emplacement. This opinion was based not on the safety of the collections, but on the engineers’ fear that the roof would not support the guns and the dome of the Gallery would interfere with the field of fire. In Boston the

Japanese galleries were immediately closed to prevent misguided demonstrations of patriotism. In New York the Met was closing at dusk, fearing that people caught in a blacked-out museum would be tempted to make off with the exhibits. The Frick had already begun to paint its skylights black, probably in vain, for, as one member dryly observed, the island of Manhattan would be quite unmistakable from the air except in the foulest weather. Indeed, skylights, so essential to the lighting of virtually every museum, would be a nearly insoluble problem from every point of view; not only could they be seen for miles, but the danger to paintings and people from shattering glass was extreme. Fear of sabotage was even greater than fear of damage—the directors envisaged bombs hidden in packages and mobs bent on destruction.

For two days these issues and others were debated: Should loan exhibitions continue? What should be evacuated and when? But on one issue the directors were united and adamant: the museums would stay open. They were fortified by a resolution of the Committee on the Conservation of Cultural Resources hand-delivered by David Finley, director of the National Gallery: there should be no general evacuation until the military and naval authorities deemed it advisable. The consensus was that it was the duty of museums to provide relaxation and a refuge from the stresses of war. If their best things were sent away, they would show objects long relegated to storage—one director wondered out loud if the public would even notice. They would provide public shelters in case of bombing. Natural History even proposed installing pianos in its shelter areas to entertain and calm the occupants.

A request from the Treasury Department for the museums’ help in advertising the good aspects of American life in order to promote the sales of war bonds, greeted coolly at first, soon attracted strong support and even an endorsement as “good” propaganda. Somewhat carried away in the heat of patriotism and by the prospect of government funding, the directors discussed organizing, with the help of Ringling Brothers, a huge travelling exhibition designed to “restate great things in America,” an idea MoMA had proposed in July 1940 but dropped as too expensive. In this excited condition, they attached a ringing resolution to the statement of intent they were readying for the press which declared: “That American museums are prepared to do their utmost in the service of the people of this country during the present conflict…. That they will be sources of inspiration illuminating the past and vivifying the present; that they will fortify the spirit on which victory depends.” At the end of the reading of this text, Juliana Force of the Whitney exclaimed, “I think it is wonderful!” and Alfred Barr suggested a standing vote on “a beautiful resolution,” which was done.

With the directors as they headed home were copies of a pamphlet written by George Stout, chief of conservation at the Fogg and the country’s greatest expert on the techniques of packing and evacuation. A veteran of World War I who had witnessed its terrible destruction at first hand, Stout had been in Paris and Germany as early as 1933 as a member of an international committee for the conservation of paintings. From his European correspondents, whose censored letters somehow reached him from Holland, Germany, and France across the submarine-infested Atlantic, he had been gleaning precise details of the effects of modern weaponry on fragile objects. The British had learned from unfortunate experience that windows should be boarded and reinforced on the outside, as bomb blasts otherwise caused coverings to be blown inward. In Spain it was found that the concussions of such blasts could affect even pictures packed and padded in boxes. Dr. Martin de Wild wrote ominously from The Hague in early March 1941 that he had “recently examined Rembrandt’s great

Night Watch

, which is now in a shelter somewhere in the dunes, well air-conditioned, but in darkness. The painting is in good condition, but of course every varnish yellows in darkness.” It had also been found that darkness promoted the growth of certain parasitical organisms on canvases. To impart these new findings to his colleagues, Stout devoted the January 1942 issue of his periodical,

Technical Studies

, to the subject, and organized a two-week symposium at the Fogg in March.

8

The major museums immediately began to move their most prized objects to safety. Officials at the National Gallery of Art were clearly nervous about taking things out of Washington, despite the fact that the board of trustees had given permission for these preparations. They worried about the effect of such action on other institutions, which would follow the lead of the museum most closely in touch with the national government. Director Finley insisted that “before any removal actually takes place … inquiries should be made of the Committee on the Conservation of Cultural Resources, National Resources Planning Board, to ascertain whether such action would conflict in any way with the general policy of the Government.”

9

There being no instructions to the contrary forthcoming from this body, the trustees saw no reason to wait, and the removal was authorized. Similar decisions were made at the Frick, the Metropolitan, and other institutions, and the cream of the great American collections now, in their turn, began journeys to undreamed-of places.

It was carefully done. The National Gallery is closed only two days of the year: Christmas and New Year’s Day. On December 30, 1941, chief curator John Walker wrote a memo instructing the staff, when questioned about missing pictures, to reply that “they cannot say what paintings are on exhibition, since certain galleries are being rearranged and some paintings

have been temporarily removed. No statement should be given as to which pictures have been removed or as to when they will again be placed on exhibition.”

10

On New Year’s Eve, after the Gallery had closed, seventy-five preselected paintings were removed from their places throughout the building. When it reopened January 2, the gaps had been filled by other works or by rearrangement of the hanging. In the storage areas the chosen pictures were inspected and packed in their specially prepared cases. On the freezing cold morning of January 6, the seventy-five (which included, suitably for the season, Botticelli’s

Adoration of the Magi

, David’s

Rest on the Flight into Egypt

, and the van Eyck

Annunciation

, as well as three Raphaels, three Rembrandts, three Yermeers, two Duccios, and two sculptures by Verrocchio—the

David

and

Giuliano de’ Medici)

left for Union Station. Only two American pictures made the cut: Savage’s

Washington Family

and the much-reproduced Gilbert Stuart portrait of the first President. The Railway Express receipt for the shipment listed the total value as $26,046,020. By January 12 the National Gallery pictures, in perfect condition, were comfortably lodged in their mountain mansion, attended day and night by rotating squads of Gallery guards and curators.

The infinite variety of the huge Metropolitan collections took far longer to remove. Galleries were quietly closed, one by one, and their contents packed in the night. By February some fifteen thousand items of every description were stashed away, having been transported in more than ninety truckloads to the wilds of suburban Philadelphia. Fearing both air raids and possible commando attacks from submarines, curators at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, true sons of Paul Revere, kept lookouts on the roof, and moved the best objects into three buildings provided by Williams College in the calm of western Massachusetts. The Frick Collection and Philadelphia Museum of Art used vaults beneath their own buildings. The Phillips Collection in Washington sent a shipment to Kansas City, and from San Diego and San Francisco collections were removed to Colorado Springs. But at the Detroit Institute of Arts, on the personal orders of Henry Ford (who believed the possibility of attack was so remote as to be nonexistent), nothing was moved at all.

11

Elsewhere, the work continued for months. In early November 1942 the President requested a progress report from the ever-sluggish Committee on the Conservation of Cultural Resources. The document, finally produced in March 1943, could report the removal, from Washington alone, of more than 40,000 cubic feet of books, manuscripts, prints, and drawings, plus the original “Star-Spangled Banner,” all of which constituted “an irreplaceable record of the development of American democracy,” to

“three inland educational institutions.” The Declaration of Independence went to Fort Knox. The fortress-like National Archives building, built in 1934 and the first government building to be air-conditioned, in 1942 alone received nearly 175,000 cubic feet of records. Even after this influx the eighteen stories of the Archives, today stuffed to the ceilings, still had plenty of room, but these sequestrations only represented a tiny fraction of the collections and archives of the nation.

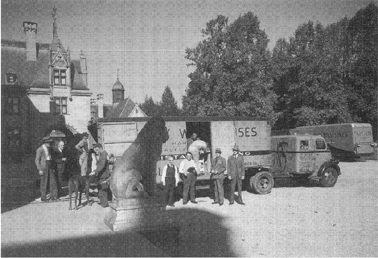

The National Gallery of Art pictures move into their shelter at Biltmore.

George Stout and his colleagues were not only interested in the protection of American collections. It had long been clear that the United States must, sooner or later, become involved in the war on the European continent. This conviction was especially strong in the eastern academic bastions traditionally oriented in that direction and was reinforced by the presence on these campuses of numbers of refugee professors. Those involved in war planning in the Roosevelt administration were well aware that these university communities were a vital source of the intelligence needed to pursue any campaign in a Europe virtually in the total control of the enemy. Within days of the fall of Paris in June 1940, a group of Harvard faculty and local citizens wishing to contribute to the war effort established the American Defense Harvard Group as a clearinghouse

which could direct available expertise to the most useful areas. Similar organizations sprang up at other centers of learning.

They would soon be set to work: the Selective Service Act was passed on September 16, 1940, and the War Department was faced with the preparation of millions of recruits for duty in undreamed-of places. They started from zero, but within weeks lectures and seminars were being prepared and delivered by American Defense volunteers. Later, the famous Office of Strategic Services (OSS) would include a large complement of these academics among its analysts.

12

Other books

Three Secrets by Opal Carew

The Pantheon by Amy Leigh Strickland

A Florentine Death by Michele Giuttari

The Makeover by Vacirca Vaughn

Dark Threat by Patricia Wentworth

Mine 'Til Monday by Ruby Laska

Whitney, My Love by Judith McNaught

Fake Boyfriend by Evan Kelsey

Zonas Húmedas by Charlotte Roche

El legado Da Vinci by Lewis Perdue