The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (24 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

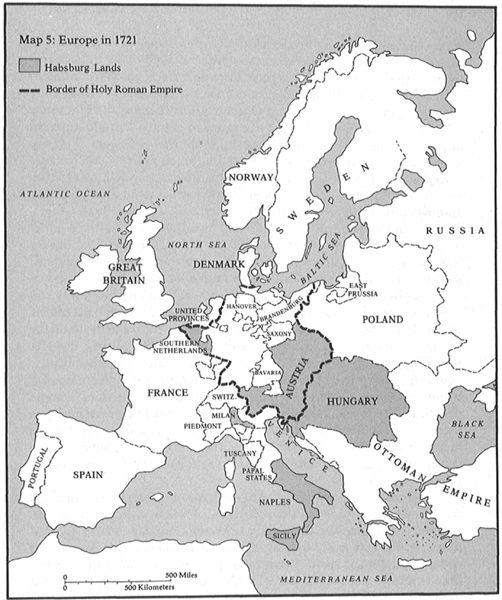

After further years of fighting (in which Charles XII was killed in yet another clash with the Danes in 1718), an exhausted, isolated Sweden finally had to admit to the loss of most of its Baltic provinces in the 1721 Peace of Nystad. It had now fallen to the second order of the powers, while Russia was in the first. Appropriately enough, to mark the 1721 victory over Sweden, Peter assumed the title Imperator. Despite the later decline of the czarist fleet, despite the great backwardness of the country, Russia had clearly shown that it, like France and Britain, “had the strength to act independently as a great power without depending on outside support.”

57

In the east as in the west of Europe there was now, in Dehio’s phrase, a “counterweight to a concentration at the center.”

58

This general balance of political, military, and economic force in Europe was underwritten by an Anglo-French

détente

lasting nearly two decades after 1715.

59

France in particular needed to recuperate

after a war which had dreadfully hurt its foreign commerce and so increased the state’s debt that the interest payments on it alone equaled the normal revenue. Furthermore, the monarchies in London and Paris, not a little fearful of their own succession, frowned upon any attempts to upset the status quo and found it mutually profitable to cooperate on many issues.

60

In 1719, for example, both powers were using force to prevent Spain from pursuing an expansionist policy in Italy. By the 1730s, however, the pattern of international relations was again changing. By this stage, the French themselves were less enthusiastic about the British link and were instead looking to recover their old position as the leading nation of Europe. The succession in France was now secure, and the years of peace had aided prosperity—and also led to a large expansion in overseas trade, challenging the maritime powers. While France under its minister Fleury rapidly improved its relations with Spain and expanded its diplomatic activities in eastern Europe, Britain under the cautious and isolationist Walpole was endeavoring to keep out of continental affairs. Even a French attack upon the Austrian possessions of Lorraine and Milan in 1733, and a French move into the Rhineland, failed to provoke a British reaction. Unable to obtain any support from the isolationist Walpole and the frightened Dutch, Vienna was forced to negotiate with Paris for the compromise peace of 1738. Bolstered by military and diplomatic successes in western Europe, by the alliance of Spain, the deference of the United Provinces, and the increasing compliance of Sweden and even Austria, France now enjoyed a prestige unequaled since the early decades of Louis XIV. This was made even more evident in the following year, when French diplomacy negotiated an end to an Austro-Russian war against the Ottoman Empire (1735–1739), thereby returning to Turkish possession many of the territories seized by the two eastern monarchies.

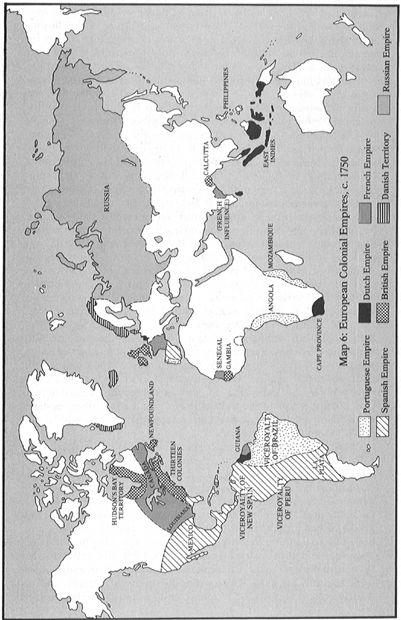

While the British under Walpole had tended to ignore these events within Europe, commercial interests and opposition politicians were much more concerned at the rising number of clashes with France’s ally, Spain, in the western hemisphere. There the rich colonial trades and conflicting settler expansionisms offered ample materials for a quarrel.

61

The resultant Anglo-Spanish war, which Walpole reluctantly agreed to in October 1739, might merely have remained one of that series of smaller regional conflicts fought between those two countries in the eighteenth century but for France’s decision to give all sorts of aid to Spain, especially “beyond the line” in the Caribbean. Compared with the 1702–1713 War of the Spanish Succession, the Bourbon powers were in a far better position to compete overseas, particularly since neither Britain’s army nor its navy was equipped to carry out the conquest of Spanish colonies so favored by the pundits at home.

The death of the Emperor Charles VI, followed by Maria Theresa’s

succession and then by Frederick the Great’s decision to take advantage of this by seizing Silesia in the winter of 1740–1741, quite transformed the situation and turned attention back to the continent. Unable to contain themselves, anti-Austrian circles in France fully supported Prussia and Bavaria in their assaults upon the Habsburg inheritance. But this in turn led to a renewal of the old Anglo-Austrian alliance, bringing substantial subsidies to the beleaguered Maria Theresa. By offering payments, by meditating to take Prussia (temporarily) and Saxony out of the war, and by the military action at Dettingen in 1743, the British government brought relief to Austria, protected Hanover, and removed French influence from Germany. As the Anglo-French antagonism turned into formal hostilities in 1744, the conflict intensified. The French army pushed northward, through the border fortresses of the Austrian Netherlands, toward the petrified Dutch. At sea, facing no significant challenge from the Bourbon fleets, the Royal Navy imposed an increasingly tight blockade upon French commerce. Overseas, the attacks and counterattacks continued, in the West Indies, up the St. Lawrence river, around Madras, along the trade routes to the Levant. Prussia, which returned to the fight against Austria in 1743, was again persuaded out of the war two years later. British subsidies could be used to keep the Austrians in order, to buy mercenaries for Hanover’s protection and even for the purchase of a Russian army to defend the Netherlands. This was, by eighteenth-century standards, an expensive way to fight a war, and many Britons complained at the increasing taxation and the trebling of the national debt; but gradually it was forcing an even more exhausted France toward a compromise peace.

Geography as much as finance—the two key elements discussed earlier—finally compelled the British and French governments to settle their differences at the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748). By that time, the French army had the Dutch at its mercy; but would that compensate for the steadily tightening grip imposed on France’s maritime commerce or for the loss of major colonies? Conversely, of what use were the British seizure of Louisburg on the St. Lawrence and the naval victories of Anson and Hawke if France conquered the Low Countries? In consequence, diplomatic talks arranged for a general return to the status quo ante, with the significant exception of Frederick’s conquest of Silesia. Both at the time and in retrospect, Aix-la-Chapelle was seen more in the nature of a truce than a lasting settlement. It left Maria Theresa keen to be revenged upon Prussia, France wondering how to be victorious overseas as well as on land, and Britain anxious to ensure that its great enemy would next time be defeated as soundly in continental warfare as it could be in a maritime/colonial struggle.

* * *

In the North American colonies, where British and French settlers (each aided by Indians and some local military garrisons) were repeatedly clashing in the early 1750s, even the word “truce” was a misnomer. There the forces involved were almost impossible to control by home governments, the more especially since a “patriot lobby” in each country pressed for support for their colonists and encouraged the view that a fundamental struggle—not merely for the Ohio and Mississippi valley regions, but for Canada, the Caribbean, India, nay, the entire extra-European world—was underway.

62

With each side dispatching further reinforcements and putting its navy on a war footing by 1755, the other states began to adjust to the prospect of another Anglo-French conflict. For Spain and the United Provinces, now plainly in the second rank and fearing that they would be ground down between these two colossi in the west, neutrality was the only solution—despite the inherent difficulties for traders like the Dutch.

63

For the eastern monarchies of Austria, Prussia, and Russia, however, abstention from an Anglo-French war in the mid-1750s was impossible. The first reason was that although some Frenchmen argued that the conflict should be fought at sea and in the colonies, the natural tendency in Paris was to attack Britain via Hanover, the strategical Achilles’ heel of the islanders. This, though, would not only alarm the German states but also compel the British to search for and subsidize military allies to check the French on the continent. The second reason was altogether more important: the Austrians were determined to recover Silesia from Prussia; and the Russians under their Czarina Elizabeth were also looking for a chance to punish the disrespectful, ambitious Frederick. Each of these powers had built up a considerable army (Prussia over 150,000 men, Austria almost 200,000, and Russia perhaps 330,000) and was calculating when to strike; but all of them were going to need subsidies from the west to keep their armies at that size. Finally, it was in the logic of things that if any of these eastern rivals found a “partner” in Paris or London, the others would be impelled to join the opposing side.

Thus, the famous “diplomatic revolution” of 1756 seemed, strategically, merely a reshuffling of the cards. France now buried its ancient differences with the Habsburgs and joined Austria and Russia in their war against Prussia, while Berlin replaced Vienna as London’s continental ally. At first sight, the Franco-Austro-Russian coalition looked the better deal. It was decidedly bigger in military terms, and by 1757 Frederick had lost all his early territorial gains and the Duke of Cumberland’s Anglo-German army had surrendered, leaving the future of Hanover—and Prussia itself—in doubt. Minorca had fallen to the French, and in the more distant theaters France and its native allies were also making gains. Overturning the treaty of Utrecht, and in Austria’s case that of Aix-la-Chapelle, now appeared distinctly possible.

The reason this did not happen was that the Anglo-Prussian combination remained superior in three vital aspects: leadership, financial staying power, and military/naval expertise.

64

Of Frederick’s achievement in harnessing the full energies of Prussia to the pursuit of victory and of his generalship on the field of battle there can be no doubt. But the prize goes, perhaps, to Pitt, who after all was not an absolute monarch but merely one of a number of politicians, who had to juggle with touchy and jealous colleagues, a volatile public, and then a new king, and simultaneously pursue an effective grand strategy. And the measure of that effectiveness could not simply be in sugar islands seized or French-backed nabobs toppled, because all these colonial gains, however valuable, would be only temporary if the foe occupied Hanover and eliminated Prussia. The correct way to a decisive victory, as Pitt gradually realized, was to complement the popular “maritime” strategy with a “continental” one, providing large-scale subsidies to Frederick’s own forces and paying for a considerable “Army of Observation” in Germany, to protect Hanover and help contain the French.

But such a policy was in turn very dependent upon having sufficient resources to survive year after year of grinding warfare. Frederick and his tax officials used every device to raise monies in Prussia, but Prussia’s capacity paled by comparison with Britain’s, which at the height of the struggle possessed a fleet of over 120 ships of the line, had more than 200,000 soldiers (including German mercenaries) on its pay lists, and was also subsidizing Prussia. In fact, the Seven Years War cost the Exchequer over £160 million, of which £60 million (37 percent) was raised on the money markets. While this further great rise in the national debt was to alarm Pitt’s colleagues and contribute to his downfall in October 1761, nevertheless the overseas trade of the country increased in every year, bringing enhanced customs receipts and prosperity. Here was an excellent example of profit being converted into power, and of British sea power being used (e.g., in the West Indies) for national profit. As the British ambassador to Prussia was informed, “we must be merchants before we are soldiers trade and maritime force depend upon each other, and … the riches which are the true resources of this country depend upon its commerce.”

65

By contrast, the economies of all the other combatants suffered heavily in this war, and even inside France the minister Choiseul had ruefully to admit that