The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (22 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

The essence of this strategic calculation was nicely expressed by the Duke of Newcastle in 1742:

France will outdo us at sea when they have nothing to fear on land. I have always maintained that our marine should protect our alliances on the Continent, and so, by diverting the expense of France, enable us to maintain our superiority at sea.

38

This British support to countries willing to “divert the expense of France” came in two chief forms. The first was direct military operations, either by peripheral raids to distract the French army or by the dispatch of a more substantial expeditionary force to fight alongside whatever allies Britain might possess at the time. The raiding strategy seemed cheaper and was much beloved by certain ministers, but it usually had negligible effects and occasionally ended in disaster (like the expedition to Walcheren of 1809). The provision of a continental army was more expensive in terms of men and money, but, as the campaigns of Marlborough and Wellington demonstrated, was also much more likely to assist in the preservation of the European balance.

The second form of British aid was financial, whether by directly buying Hessian and other mercenaries to fight against France, or by giving subsidies to the allies. Frederick the Great, for example, received from the British the substantial sum of £675,000 each year from 1757 to 1760; and in the closing stages of the Napoleonic War the flow of British funds reached far greater proportions (e.g., £11 million to various allies in 1813 alone, and £65 million for the war as a whole). But all this had been possible only because the expansion of British trade and commerce, particularly in the lucrative overseas markets, allowed the government to raise loans and taxes of unprecedented amounts without suffering national bankruptcy. Thus, while diverting “the expense of France” inside Europe was a costly business, it usually ensured that the French could neither mount a sustained campaign against maritime trade nor so dominate the European continent that they would be free to threaten an invasion of the home islands—which in turn permitted London to finance its wars and to subsidize its allies. Geographical advantage and economic benefit were thus merged to enable the British brilliantly to pursue a Janus-faced strategy: “with one face turned towards the Continent to trim the balance of power and the other directed at sea to strengthen her maritime dominance.”

39

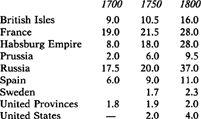

Only after one grasps the importance of the financial and geographical factors described above can one make full sense of the statistics of the growing populations and military/naval strengths of the powers in this period (see Tables

3

–

5

).

Table 3. Populations of the Powers, 1700-1800

40

(millions)

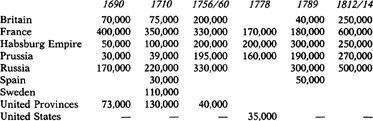

Table 4. Size of Armies, 1690–1814

41

(men)

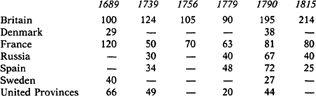

Table 5. Size of Navies, 1689–1815

42

(ships of the line)

As readers familiar with statistics will be aware, such crude figures have to be treated with extreme care. Population totals, especially in the early period, are merely guesses (and in Russia’s case the margin for error could be several millions). Army sizes fluctuated widely, depending upon whether the date chosen is at the outset, the midpoint, or the culmination of a particular war; and the total figures often include substantial mercenary units and (in Napoleon’s case) even the troops of reluctantly co-opted allies. The number of ships of the line indicated neither their readiness for battle nor, necessarily, the availability of trained crews to man them. Moreover, statistics take no account of generalship or seamanship, of competence or neglect, of

national fervor or faintheartedness. Even so, it might appear that the above figures at least

roughly

reflect the chief power-political trends of the age: France and, increasingly, Russia lead in population and military terms; Britain is usually unchallenged at sea; Prussia overtakes Spain, Sweden, and the United Provinces; and France comes closer to dominating Europe with the enormous armies of Louis XIV and Napoleon than at any time in the intervening century.

Aware of the financial and geographical dimensions of these 150 years of Great Power struggles, however, one can see that further refinements have to be made to the picture suggested in these three tables. For example, the swift decline of the United Provinces relative to other nations in respect to army size was not repeated in the area of war finance, where its role was crucial for a very long while. The nonmilitary character of the United States conceals the fact that it could pose a considerable strategical distraction. The figures also understate the military contribution of Britain, since it might be subsidizing 100,000 allied troops (in 1813, 450,000!) as well as providing for its own army, and naval personnel of 140,000 in 1813–1814;

43

conversely, the true strength of Prussia and the Habsburg Empire, dependent on subsidies during most wars, would be exaggerated if one merely considered the size of their armies. As noted above, the enormous military establishments of France were rendered less effective through financial weaknesses and geostrategical obstacles, while those of Russia were eroded by economic backwardness and sheer distance. The strengths and weaknesses of each of these Powers ought to be borne in mind as we turn to a more detailed examination of the wars themselves.

When Louis XIV took over full direction of the French government in March 1661, the European scene was particularly favorable to a monarch determined to impose his views upon it.

44

To the south, Spain was still exhausting itself in the futile attempt to recover Portugal. Across the Channel, a restored monarchy under Charles II was trying to find its feet, and in English commercial circles great jealousy of the Dutch existed. In the north, a recent war had left both Denmark and Sweden weakened. In Germany, the Protestant princes watched suspiciously for any fresh Habsburg attempt to improve its position, but the imperial government in Vienna had problems enough in Hungary and Transylvania, and slightly later with a revival of Ottoman power. Poland was already wilting under the effort of fending off Swedish and Muscovite predators. Thus French diplomacy, in the best traditions of Richelieu, could easily take advantage of these circumstances, playing

off the Portuguese against Spain, the Magyars, Turks, and German princes against Austria, and the English against the Dutch—while buttressing France’s own geographical (and army-recruitment) position by its important 1663 treaty with the Swiss cantons. All this gave Louis XIV time enough to establish himself as absolute monarch, secure from the internal challenges which had afflicted French governments during the preceding century. More important still, it gave Colbert, Le Tellier, and the other key ministers the chance to overhaul the administration and to lavish resources upon the army and the navy in anticipation of the Sun King’s pursuit of glory.

45

It was therefore all too easy for Louis to try to “round off” the borders of France in the early stages of his reign, the more especially since Anglo-Dutch relations had deteriorated into open hostilities by 1665 (the Second Anglo-Dutch War). Although France was pledged to support the United Provinces, it actually played little part in the campaigns at sea and instead prepared itself for an invasion of the southern Netherlands, which were still owned by a weakened Spain. When the French finally launched their invasion, in May 1667, town after town quickly fell into their hands. What then followed was an early example of the rapid diplomatic shifts of this period. The English and the Dutch, wearying of their mutually unprofitable war and fearing French ambitions, made peace at Breda in July and, joined by Sweden, sought to “mediate” in the Franco-Spanish dispute in order to limit Louis’s gains. The 1668 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle achieved just that, but at the cost of infuriating the French king, who eventually made up his mind to be revenged upon the United Provinces, which he perceived to be the chief obstacle to his ambitions. For the next few years, while Colbert waged his tariff war against the Dutch, the French army and navy were further built up. Secret diplomacy seduced England and Sweden from their alliance with the United Provinces and quieted the fears of the Austrians and the German states. By 1672 the French war machine, aided by the English at sea, was ready to strike.

Although it was London which first declared war upon the United Provinces, the dismal English effort in the third Anglo-Dutch conflict of 1672–1674 requires minimal space here. Checked by the brilliant efforts of de Ruyter at sea, and therefore unable to achieve anything on land, Charles II’s government came under increasing domestic criticism: evidence of political duplicity and financial mismanagement, and a strong dislike of being allied to an autocratic, Catholic power like France, made the war unpopular and forced the government to pull out of it by 1674. In retrospect, it is a reminder of how immature and uncertain the political, financial, and administrative bases of English power still were under the later Stuarts.

46

London’s change of policy was of

international

importance, however, in that it partly reflected the widespread alarm which Louis XIV’s designs were now arousing

throughout Europe. Within another year, Dutch diplomacy and subsidies found many allies willing to throw their weight against the French. German principalities, Brandenburg (which defeated France’s only remaining partner, Sweden, at Fehrbellin in 1675), Denmark, Spain, and the Habsburg Empire all entered the issue. It was not that this coalition of states was strong enough to

overwhelm

France; most of them had smallish armies, and distractions on their own flanks; and the core of the anti-French alliance remained the United Provinces under their new leader, William of Orange. But the watery barrier in the north and the vulnerability of the French army’s lines against various foes in the Rhineland meant that Louis himself could make no dramatic gains. A similar sort of stalemate existed at sea; the French navy controlled the Mediterranean, Dutch and Danish fleets held the Baltic, and neither side could prevail in the West Indies. Both French and Dutch commerce were badly affected in this war, to the indirect benefit of neutrals like the British. By 1678, in fact, the Amsterdam merchant classes had pushed their own government into a separate peace with France, which in turn meant that the German states (reliant upon Dutch subsidies) could not continue to fight on their own.

Although the Nymegen peace treaties of 1678–1679 brought the open fighting to an end, Louis XIV’s evident desire to round off France’s northern borders, his claim to be “the arbiter of Europe,” and the alarming fact that he was maintaining an army of 200,000 troops in peacetime disquieted Germans, Dutchmen, Spaniards, and Englishmen alike.

47

This did not mean an immediate return to war. The Dutch merchants preferred to trade in peace; the German princes, like Charles II of England, were tied to Paris by subsidies; and the Habsburg Empire was engaged in a desperate struggle with the Turks. When Spain endeavored to protect its Luxembourg territories from France in 1683, therefore, it had to fight alone and suffer inevitable defeat.