The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (60 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

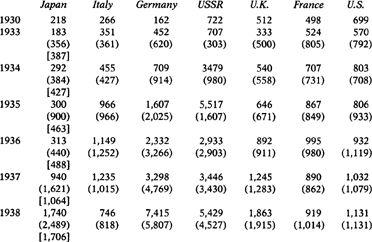

It is in this technological-economic context (as well as in the diplomatic context) that the varying patterns of Great Power rearmament in the 1930s can best be understood. There are many disparities in the compilation of the actual annual totals of defense expenditures by individual nations in this decade, but

Table 27

can serve as a fair guide to what was happening.

Table 27. Defense Expenditures of the Great Powers, 1930–1938

50

(millions of current dollars)

Seen in this comparative light, the Italian problem becomes clearer. It had not been a great spender on armaments in absolute terms during the first half of the 1930s, although even then it had needed to devote a higher proportion of its national income to the armed services than probably all other states except the USSR. But the extended Abyssinian campaign, overlapped by the intervention in Spain, led to greatly increased expenditures between 1935 and 1937. Thus part of Italian defense spending in those years was devoted to current operations, and not to the buildup of the services or the armaments industry. On the contrary, the Abyssinian and Spanish adventures gravely weakened

Italy, not only because of losses in the field, but also because the longer it fought, the more it needed to import—and pay for—vital strategic raw materials, causing the Bank of Italy’s reserves to shrink to almost nothing by 1939. Unable to afford the machine tools and other equipment needed to modernize the air force and the army, the country was probably getting

weaker

in the two to three years prior to 1940. The army was not helped by its own reorganization, since the device of creating half again as many divisions by simply reducing each division from three to two regiments led to many officer promotions but to no real increase in efficiency. The air force, supported (if that is the right word) by an industry which was

less

productive than that of 1915–1918, claimed that it had over 8,500 planes; further investigations reduced that total to 454 bombers and 129 fighters, few of which would be regarded as first-rate in other air forces.

51

Without proper tanks or antiaircraft guns or fast fighters or decent bombs or aircraft carriers or radar or foreign currency or adequate logistics, Mussolini in 1940 threw his country into another Great Power war, on the assumption that it was already won. In fact, only a miracle, or the Germans, could prevent a debacle of epic proportions.

All of this emphasis upon weaponry and numbers does, of course, ignore the elements of leadership, quality of personnel, and national proclivity for combat; but the sad fact was that, far from compensating for Italy’s matériel deficiencies, those elements merely added to its relative weakness. Despite superficial fascist indoctrination, nothing in Italian society and political culture had altered between 1900 and 1930 to make the army a more attractive career to talented, ambitious males; on the contrary, its collective inefficiency, lack of initiative, and concern for personal career prospects was stultifying—and amazed the German attachés and other military observers. The army was not the compliant tool of Mussolini; it could, and often did, obstruct his wishes, offering innumerable reasons why things could not be done. Its fate was to be thrust, often without prior consultation, into conflicts where something

had

to be done. Dominated by its cautious and inadequately trained senior officers, and lacking a backbone of experienced NCOs, the army’s plight in the event of a Great Power war was hopeless; and the navy (except for the enterprising midget submarines) was little better off. If the officer corps and crews of the Regia Aeronautica were better educated and better trained, that would avail them little when they were still flying obsolescent aircraft, whose engines succumbed to the desert sands, whose bombs were hopeless, and whose firepower was pathetic. Perhaps it hardly needs saying that there was no chiefs of staff committee to coordinate plans between the services, or to discuss (let alone settle) defense priorities.

Finally, there was Mussolini himself, a strategical liability of the first order. He was not, it has been argued, the all-powerful leader on

the lines of Hitler which he projected himself as being. King Victor Emmanuel III strove to preserve his prerogatives, and succeeded in keeping the loyalties of much of the bureaucracy and the officer corps. The papacy was also an independent, and rival, focus of authority for many Italians. Neither the great industrialists nor the recalcitrant peasantry were enthusiastic about the regime by the 1930s; and the National Fascist Party itself, or at least its regional bosses, seemed more concerned with the distribution of jobs than the pursuit of national glory.

52

But even had Mussolini’s rule been absolute, Italy’s position would be no better, given II Duce’s penchant for self-delusion, resort to bombast and bluster, congenital lying, inability to act and think effectively, and governmental incompetence.

53

In 1939 and 1940, the western Allies frequently considered the pros and cons of having Italy fighting on Germany’s side rather than remaining neutral. On the whole, the British chiefs of staff preferred Italy to be kept out of the war, so as to preserve peace in the Mediterranean and Near East; but there were powerful counterarguments, which seem in retrospect to have been correct.

54

Rarely in the history of human conflict has it been argued that the entry of an additional foe would hurt one’s enemy more than oneself; but Mussolini’s Italy was, in that way at least, unique.

The challenge to the status quo posed by Japan was also of a very individual sort, but needed to be taken much more seriously by the established Powers. In the world of the 1920s and 1930s, heavily colored by racist and cultural prejudices, many in the West tended to dismiss the Japanese as “little yellow men”; only during the devastating attacks upon Pearl Harbor, Malaya, and the Philippines was this crude stereotype of a myopic, stunted, unmechanical people revealed for the nonsense it was.

55

The Japanese navy trained hard, both for day and night fighting, and learned well; its attachés fed a continual stream of intelligence back to the planners and ship designers in Tokyo. Both the army and the naval air forces were also well trained, with a large stock of competent pilots and dedicated crewmen.

56

As for the army proper, its determined and hyperpatriotic officer corps stood at the head of a force imbued with the

bushido

spirit; they were formidable troops both in offensive and defensive warfare. The fanatical zeal which led to the assassination of (allegedly) weak ministers could easily be transformed into battlefield effectiveness. While other armies merely talked of fighting to the last man, Japanese soldiers took the phrase literally, and did so.

But what distinguished the Japanese from, say, Zulu warriors was that by this period the former possessed military-technical superiority as well as sheer bravery. The pre-1914 process of industrialization had been immensely boosted by the First World War, partly because of

Allied contracts for munitions and a strong demand for Japanese shipping, partly because its own exporters could step into Asian markets which the West could no longer supply.

57

Imports and exports tripled during the war, steel and cement production more than doubled, and great advances were made in chemical and electrical industries. As with the United States, Japan’s foreign debts were liquidated during the war and it became a creditor. It also became a major shipbuilding nation, launching 650,000 tons in 1919 compared with a mere 85,000 tons in 1914. As the League of Nations

World Economic Survey

showed, the war had boosted its manufacturing production even more than that of the United States, and the continuation of that growth during the 1919–1938 period meant that it was second only to the Soviet Union in its overall rate of expansion (see

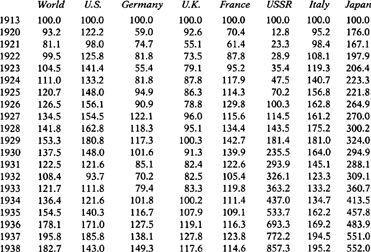

Table 28

).

Table 28. Annual Indices of Manufacturing Production, 1913–1938

58

(1913 = 100)

By 1938, in fact, Japan had not only become much stronger economically than Italy, but had also overtaken France in all of the indices of manufacturing and industrial production (see

Tables 14

–

18

above). Had its military leaders not gone to war in China in 1937 and, more disastrously, in the Pacific in 1941, one is tempted to conclude that it would also have overtaken British output well before actually doing so, in the mid-1960s.

This is not to say that Japan had effortlessly overcome all of its economic problems, but merely that it was growing markedly stronger. Because of its primitive banking system, it had not found it

easy to adjust to becoming a creditor nation during the First World War, and its handling of the money supply had caused great inflation—not to mention the “rice riots” of 1919.

59

As Europe resumed its peacetime production of textiles, merchant vessels, and other goods, Japan felt the pressure of renewed competition; the cost of its manufacturing, at this stage, was still generally higher than in the West. Furthermore, a heavy proportion of the Japanese population remained in small-plot agriculture, and these groups suffered not only from rising rice imports from Taiwan and Korea, but also from the collapse of the vital silk export trade when American demand fell away after 1930. Seeking to alleviate these miseries by imperial expansion was always a temptation for worried or ambitious Japanese politicians—the conquest of Manchuria, for example, meant economic benefits as well as military gains. On the other hand, when Japanese industry and commerce recovered during the 1930s, partly through rearmament and partly through the exploitation of captive East Asian markets, so its dependence upon imported raw materials grew (in this respect, at least, it was similar to Italy). As the Japanese steel industry expanded, it required larger amounts of pig iron and ore from China and Malaya. Domestic supplies of coal and copper were also inadequate for industry’s requirements; but even that was less critical than the country’s near-total reliance upon petroleum fuels of all sorts. Japan’s quest for “economic security”

60

—a self-evident good in the eyes of its fervent nationalists and the military rulers—drove it ever forward, but with mixed results.

Despite—and, of course, in some ways because of—these economic difficulties, the finance ministry under Takahashi was willing to borrow recklessly in the early 1930s in order to allocate more to the armed services, whose share of government spending rose from 31 percent in 1931–1932 to 47 percent in 1936–1937;

61

when he finally took alarm at the economic consequences and sought to modify further increases, he was promptly assassinated by the militarists, and armaments expenditures spiraled upward. By the following year, the armed services were taking 70 percent of government expenditure and Japan was thus spending, in absolute terms, more than any of the far wealthier democracies. Thus the Japanese armed services were in a far better position than those of Italy by the late 1930s, and possibly also those of France and Britain. The Imperial Japanese Navy, legally restricted by the Washington Treaty to slightly over half the size of either the British or American navy, was in reality much more powerful than that. While the two leading naval powers economized during the 1920s and early 1930s, Japan built right up to the treaty limits—and, indeed, secretly went far beyond them. Its heavy cruisers, for example, displaced closer to 14,000 tons than the 8,000 tons required by the treaty. All of the Japanese major warships were fast and very heavily armed; its older

battleships had been modernized, and by the late 1930s it was laying down the gigantic

Yamato-

class vessels, larger than anything else in the world. The most important element of all, although the battleship admirals didn’t properly realize it, was Japan’s powerful and efficient naval air service, with 3,000 aircraft and 3,500 pilots, which centered upon the ten carriers in the fleet but also included some deadly-efficient bomber and torpedo-carrying squadrons on land. Japanese torpedoes were of unequaled power and quality. Finally, the country also possessed the world’s third-largest merchant marine, although (curiously) the navy itself virtually neglected antisubmarine warfare.

62