The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (56 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

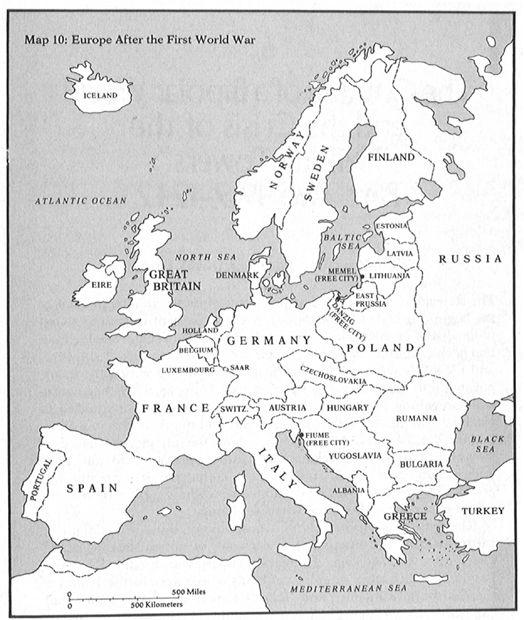

The most striking change in Europe, measured in territorial-juridical terms, was the emergence of a cluster of nation-states—Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—in place of lands which were formerly part of the Habsburg, Romanov, and Hohenzollen empires. While the ethnically coherent Germany suffered far smaller territorial losses in eastern Europe than either Soviet Russia or the totally dissolved Austro-Hungarian Empire, its power was hurt in other ways: by the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France, and by border rectifications with Belgium and Denmark; by the Allied military occupation of the Rhine-land, and the French economic exploitation of the Saarland; by the unprecedented “demilitarization” terms (e.g., minuscule army and coastal-defense navy, no air force, tanks, or submarines, abolition of Prussian General Staff); and by an enormous reparations bill. In addition, Germany also lost its extensive colonial empire to Britain, the self-governing dominions, and France—just as Turkey found its Near East territories turned into British and French mandates, distantly

supervised by the new League of Nations. In the Far East, Japan inherited the former German island groups north of the equator, although it returned Shantung to China in 1922. At the 1921–1922 Washington Conference, the powers recognized the territorial status quo in the Pacific and Far East, and agreed to restrict the size of their battle fleets according to relative formulae, thereby heading off an Anglo-American-Japanese naval race. In both the West and the East, therefore, the international system appeared to have been stabilized by the early 1920s—and what difficulties remained (or might arise in the future) could now be dealt with by the League of Nations, which met regularly at Geneva despite the surprise defection of the United States.

1

The sudden American retreat into at least relative diplomatic isolationism after 1920 seemed yet another contradiction to those world-power trends which, as detailed above, had been under way since the 1890s. To the prophets of world politics in that earlier period, it was self-evident that the international scene was going to be increasingly influenced, if not dominated, by the three rising powers of Germany, Russia, and the United States. Instead, the first-named had been decisively defeated, the second had collapsed in revolution and then withdrawn into its Bolshevik-led isolation, and the third, although clearly the most powerful nation in the world by 1919, also preferred to retreat from the center of the diplomatic stage. In consequence, international affairs during the 1920s and beyond still seemed to focus either upon the actions of France and Britain, even though both countries had been badly hurt by the First World War, or upon the deliberations of the League, in which French and British statesmen were preeminent. Austria-Hungary was now gone. Italy, where the National Fascist Party under Mussolini was consolidating its hold after 1922, was relatively quiescent. Japan, too, appeared tranquil following the 1921–1922 Washington Conference decisions.

In a curious and (as will be seen) artificial way, therefore, it still seemed a Eurocentered world. The diplomatic histories of this period focus heavily upon France’s “search for security” against a future German resurgence. Having lost a special Anglo-American military guarantee at the same time as the U.S. Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles, the French sought to create a variety of substitutes: encouraging the formation of an “antirevisionist” bloc of states in eastern Europe (the so-called Little Entente of 1921); concluding individual alliances with Belgium (1920), Poland (1921), Czechoslovakia (1924), Rumania (1926), and Yugoslavia (1927); maintaining a very large army and air force to overawe the Germans and intervening—as in the 1923 Ruhr crisis—when Germany defaulted on the reparation payments; and endeavoring to persuade successive British administrations to provide a new military guarantee of France’s borders, something which was achieved only indirectly in the multilateral

Locarno Treaty of 1925.

2

It was also a period of intense financial diplomacy, since the interacting problem of German reparations and Allied war debts bedeviled relations not only between the victors and the vanquished, but also between the United States and its former European allies.

3

The financial compromise of the Dawes Plan (1924) eased much of this turbulence, and in turn prepared the ground for the Locarno Treaty the following year; that was followed by Germany’s entry into the League and then the amended financial settlement of the Young Plan (1929). By the late 1920s, indeed, with prosperity returning to Europe, with the League apparently accepted as an important new element in the international system, and with a plethora of states solemnly agreeing (under the 1928 Pact of Paris) not to resort to war to settle future disputes, the diplomatic stage seemed to have returned to normal. Statesmen such as Stresemann, Briand, and Austen Chamberlain appeared, in their way, the latter-day equivalents of Metternich and Bismarck, meeting at this or that European spa to settle the affairs of the world.

Despite these superficial impressions, however, the underlying structures of the post-1919 international system were significantly different from, and much more fragile than, those which influenced diplomacy a half-century earlier. In the first place, the population losses and economic disruptions caused by four and a half years of “total” war were immense. Around 8 million men were killed in actual fighting, with another 7 million permanently disabled and a further 15 million “more or less seriously wounded”

4

—the vast majority of these being in the prime of their productive life. In addition, Europe

excluding

Russia probably lost over 5 million civilian casualties through what has been termed “war-induced causes”—“disease, famine and privation consequent upon the war as well as those wrought by military conflict”;

5

the Russian total, compounded by the heavy losses in the civil war, was much larger. The wartime “birth deficits” (caused by so many men being absent at the front, and the populations thereby not renewing themselves at the normal prewar rate) were also extremely high. Finally, even as the major battles ground to a halt, fighting and massacres occurred during the postwar border conflicts in, for example, eastern Europe, Armenia, and Poland; and none of these war-weakened regions escaped the dreadful influenza epidemic of 1918–1919, which carried off further millions. Thus, the final casualty list for this extended period might have been as much as 60 million people, with nearly half of these losses occurring in Russia, and with France, Germany, and Italy also being badly hit. There is no known way of measuring the personal anguish and the psychological shocks involved in such a human catastrophe, but it is easy to see why the

participants—statesmen as well as peasants—were so deeply affected by it all.

The material costs of the war were also unprecedented and seemed, to those who viewed the devastated landscapes of northern France, Poland, and Serbia, even more shocking: hundreds of thousands of houses were destroyed, farms gutted, roads and railways and telegraph lines blown up, livestock slaughtered, forests pulverized, and vast tracts of land rendered unfit for farming because of unexploded shells and mines. When the shipping losses, the direct and indirect costs of mobilization, and the monies raised by the combatants are added to the list, the total charge becomes so huge as to be virtually incomprehensible: in fact, some $260 billion, which, according to one calculation, “represented about six and a half times the sum of all the national debt accumulated in the world from the end of the eighteenth century up to the eve of the First World War.”

6

After decades of growth, world manufacturing production turned sharply down; in 1920 it was still 7 percent less than in 1913, agricultural production was about one-third below normal, and the volume of exports was only around half what it was in the prewar period. While the growth of the European economy as a whole had been retarded, perhaps as much as by eight years,

*

individual countries were much more severely affected. Predictably, Russia in the turmoil of 1920 recorded the lowest industrial output, equal to a mere 13 percent of the 1913 figure; but in Germany, France, Belgium, and much of eastern Europe, industrial output was at least 30 percent lower than before the conflict.

7

If some societies were the more heavily affected by the war, then others of course escaped lightly—and many improved their position. For the fact was that modern war, and the industrial productivity generated by it, also had positive effects. In strictly economic and technological terms, these years had seen many advances: in automobile and truck production, in aviation, in oil refining and chemicals, in the electrical and dyestuff and alloy-steel industries, in refrigeration and canning, and in a whole host of other industries.

8

Naturally, it proved easier to develop and to benefit commercially from such advances if one’s economy was far from the disruption of the front line; which is why the United States itself, but also Canada, Australia, South Africa, India, and parts of South America, found their economies stimulated by the industrial, raw-material, and foodstuffs demand of a Europe convulsed by a war of attrition. As in previous mercantilist conflicts, one country’s loss was often another’s gain—provided the

latter avoided the costs of war, or was at least protected from the full blast of battle.

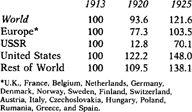

Table 26. World Indices of Manufacturing Production, 1913-1925

9

Such figures on world manufacturing production are very illuminating in this respect, since they record the extent to which Europe (and especially the USSR) were hurt by the war, while other regions gained substantially. To some degree, of course, the spread of industrialization from Europe to the Americas, Japan, India, and Australasia, and the increasing share of these latter territories in world trade, was simply the continuation of economic trends which had been in evidence since the late nineteenth century. Thus, according to one arcane calculation already mentioned earlier, the United States pre-1914 growth was such that it probably would have overtaken Europe in total output in the year 1925;

10

what the war did was to accelerate that event by a mere six years, to 1919. On the other hand, unlike the 1880–1913 changes, these particular shifts in the global economic balances were

not

taking place in peacetime over several decades and in accord with market forces. Instead, the agencies of war and blockade created their own peremptory demands and thus massively distorted the natural patterns of world production and trade. For example, shipbuilding capacity (especially in the United States) had been enormously increased in the middle of the war to counter the sinkings by U-boats; but after 1919–1920, there were excess berths across the globe. Again, the output of the steel industries of continental Europe had fallen during the war, whereas that of the United States and Britain had risen sharply; but when the European steel producers recovered, the excess capacity was horrific. This problem also affected an even greater sector of the economy—agriculture. During the war years, farm output in continental Europe had shriveled and Russia’s prewar export trade in grain had disappeared, whereas there had been large increases in output in North and South America and in Australasia, whose farmers were the decided (if unpremeditating) beneficiaries of the archduke’s death. But when European agriculture recovered by the late 1920s, producers across the world faced a fall-off in demand, and tumbling prices.

11

These sorts of structural distortions affected all regions,

but were felt nowhere as severely as in east-central Europe, where the fragile “successor states” grappled with new boundaries, dislocated markets, and distorted communications. Making peace at Versailles and redrawing the map of Europe along (roughly) ethnic lines did not of itself guarantee a restoration of economic stability.