The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (52 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

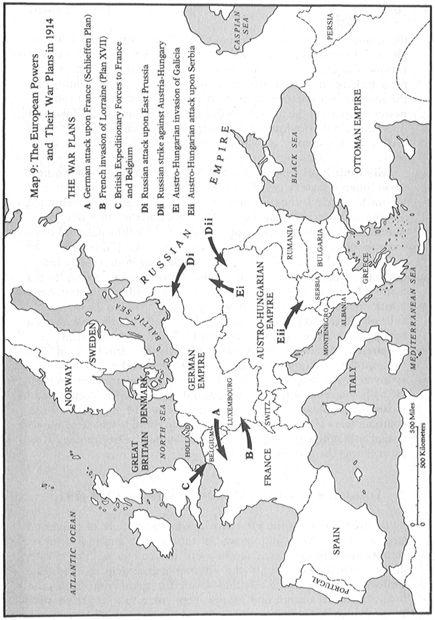

The point about all of these war plans was not merely that they appear, in retrospect, like a line of dominoes which would tumble when the first one fell. What was also important was that since a coalition war was much more likely than in, say, 1859 or 1870, the prospects that the conflict would be prolonged were also that much greater, although few contemporaries appear to have realized it. The notorious miscalculation that the war begun in July/August 1914 would be “over by Christmas” has usually been explained away by the failure to anticipate that quick-firing artillery and machine guns made a

guerre de manoeuvre

impossible and forced the masses of troops into trenches, from where they could rarely be dislodged; and that the later resort to prolonged artillery bombardments and enormous infantry offensives provided no solution, since the shelling merely churned up

the ground and gave the enemy notice of where the attack would take place.

190

In much the same way, it is argued that the admiralties of Europe also misread the war that was to come, preparing themselves for a decisive battle-fleet encounter and not properly appreciating that the geographical contours of the North Sea and Mediterranean and the newer weapons of the mine, torpedo, and submarine would make fleet operations in the traditional style very difficult indeed.

191

Both at sea and on land, therefore, a swift victory was unlikely for technical reasons.

All of this is, of course, true, but it needs to be put in the context of the alliance system itself.

192

After all, had the Russians been allowed to attack Austria-Hungary alone, or had the Germans been permitted a rerun of their 1870 war against France while the other powers remained neutral, the prospects of victory (even if a little delayed) seem incontestable. But these coalitions meant that even if one belligerent was heavily beaten in a campaign or saw that its resources were inadequate to sustain further conflict, it was encouraged to remain in the war by the hope—and promises—of aid from its allies. Looking ahead a little, France could hardly have kept going after the disastrous Nivelle offensive and the 1917 mutinies, Italy could hardly have avoided collapse after its defeat at Caporetto in 1917, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire could hardly have continued after the dreadful losses of 1916 (or even the 1914 failures in Galicia and Serbia) had not each of them received timely support from its allies. Thus, the alliance system itself virtually guaranteed that the war would

not

be swiftly decided, and meant in turn that victory in this lengthy duel would go—as in the great coalition wars of the eighteenth century—to the side whose combination of both military/naval

and

financial/industrial/technological resources was the greatest.

Before examining the First World War in the light of the grand strategy of the two coalitions and of the military and industrial resources available to them, it may be useful to recall the position of each of the Great Powers within the international system of 1914. The United States was on the sidelines—even if its great commercial and financial ties to Britain and France were going to make impossible Wilson’s plea that it be “neutral in thought as in deed.”

193

Japan liberally interpreted the terms of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance to occupy the German possessions in China and in the central Pacific; neither this nor its naval-escort duties further afield would be decisive, but for the Allies it was obviously far better to have a friendly Japan than a hostile one. Italy, by contrast, chose neutrality in 1914 and in view of its

military and socioeconomic fragility would have been wise to maintain that policy: if its 1915 decision to enter the war

against

the Central Powers was a blow to Austria-Hungary, it is difficult to say that it was the significant benefit to Britain, France, and Russia that Allied diplomats had hoped for.

194

In much the same way, it was difficult to say who benefited most from the Turkish decision to enter the war on Berlin’s side in November 1914. True, it blocked the Straits, and thus Russia’s grain exports and arms imports; but by 1915 it would have been difficult to transport Russian wheat

anywhere

, and there were no “spare” munitions in the west. On the other hand, Turkey’s decision opened the Near East to French and (especially) British imperial expansion—though it also distracted the imperialists in India and Whitehall from full concentration along the western front.

195

The really critical positions, therefore, were those occupied by the “Big Five” powers in Europe. By this stage, it is artificial to treat Austria-Hungary as something entirely separate from Germany, for while Vienna’s aims often diverged from Berlin’s on many issues, it could make war or peace—and probably survive as a quasi-independent Great Power—only at the behest of its powerful ally.

196

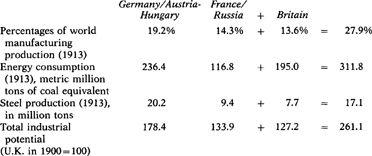

The Austro-German combination was formidable. Its front-line armies were considerably smaller than those of the French and Russian, but they operated on efficient internal lines and could be supplemented by a swelling number of recruits. As can be seen from

Table 22

below, they also enjoyed a considerable superiority in industrial and technological strength over the Dual Alliance.

The position of France and Russia was, of course, exactly the converse. Separated from each other by more than half of Europe, France and Russia would find it difficult (to say the least) to coordinate their military strategy. And while they appeared to enjoy a large lead in army strengths at the outset of the war, this was reduced by the clever German use of trained reservists in the front-line fighting, and this lead declined still further after the reckless Franco-Russian offensives in the autumn of 1914. With victory no longer going to the swift, it was more and more likely that it would go to the strong; and the industrial indices were not encouraging. Had the Franco-Russe alone been involved in a lengthy, “total” war against the Central Powers, it is hard to think how it could have won.

But the fact was, of course, that the German decision to launch a preemptive strike upon France by way of Belgium gave the upper hand to British interventionists.

197

Whether it was for the traditional reasons of the “balance of power” or in defense of “poor little Belgium,” the British decision to declare war upon Germany was critical, though Britain’s small, long-service army could affect the overall military equilibrium only marginally—at least until that force had transformed itself into a mass conscript army on continental lines. But since the

war

was

going to last longer than a few months, Britain’s strengths were considerable. Its navy could neutralize the German fleet and blockade the Central Powers—which would not bring the latter to their knees, but would deny them access to sources of supply outside continental Europe. Conversely, it ensured free access to supply sources for the Allied Powers (except when later interrupted by the U-boat campaign); and this advantage was compounded by the fact that Britain was such a wealthy trading country, with extensive links across the globe and enormous overseas investments, some of which at least could be liquidated to pay for dollar purchases. Diplomatically, these overseas ties meant that Britain’s decision to intervene influenced Japan’s action in the Far East, Italy’s declaration of neutrality (and later switch), and the generally benevolent stance of the United States. More direct overseas support was provided, naturally enough, by the self-governing dominions and by India, whose troops moved swiftly into Germany’s colonial empire and then against Turkey.

In addition, Britain’s still-enormous industrial and financial resources could be deployed in Europe, both in raising loans and sending munitions to France, Belgium, Russia, and Italy, and in supplying and paying for the large army to be employed by Haig on the western front. The economic indices in

Table 22

show the significance of Britain’s intervention in power terms.

Table 22. Industrial/Technological Comparisons of the 1914 Alliances (taken from

Tables 15

–

18

above)

To be sure, this made a significant rather than an overwhelming superiority in matériel possessed by the Allies, and the addition of Italy in 1915 would not weigh the scales much further in their favor. Yet if victory in a prolonged Great Power war usually went to the coalition with the largest productive base, the obvious questions arise as to why the Allies were failing to prevail even after two or three years of fighting—and by 1917 were in some danger of losing—and why they then found it vital to secure American entry into the conflict.

One part of the answer must be that the areas in which the Allies were strong were unlikely to produce a swift or decisive victory over the Central Powers. The German colonial empire in 1914 was economically so insignificant that (apart from Nauru phosphates) its loss meant very little. The elimination of German overseas trade was certainly more damaging, but not to the extent that British devotees of “the influence of sea power” imagined; for the German export trades were redeployed for war production, the Central Powers bloc was virtually self-sufficient in foodstuffs provided its transport system was maintained, military conquests (e.g., of Luxembourg ores, Rumanian wheat and oil) canceled out many raw-materials shortages, and other supplies came via neutral neighbors. The maritime blockade had an effect, but only when it was applied in conjunction with military pressures on all fronts, and even then it worked very slowly. Finally, the other traditional weapon in the British armory, peripheral operations on the lines of the Peninsular War of 1808–1814, could not be used against the German coast, since its sea-based and land-based defenses were too formidable; and when it was employed against weaker powers—at Gallipoli, for example, or Salonika—operational failures on the Allied side and newer weapons (mine fields, quick-firing shore batteries) on the defender’s side, blunted their hoped-for impact. As in the Second World War, every search for the “soft underbelly” of the enemy coalition took Allied troops away from fighting in France.

198

The same points can be made about the overwhelming Allied naval superiority. The geography of the North Sea and the Mediterranean meant that the main Allied lines of communication were secure

without

needing to seek out their enemies’ vessels in harbor or to mount a risky close blockade of their shores. On the contrary, it was incumbent upon the German and Austro-Hungarian fleets to come out and challenge the Anglo-French-Italian navies if they wanted to gain “command of the sea”; for if they remained in port, they were useless. Yet neither of the navies of the Central Powers wished to send its battle fleets on a virtual suicide mission against vastly superior forces. Thus, the few surface naval clashes which did occur were chance encounters (e.g., Dogger Bank, Jutland), and were strategically unimportant except insofar as they confirmed the Allied control of the seaways. The prospect of further encounters was reduced by the threat posed to warships by mines, submarines, and scouting aircraft or Zeppelins, which made the commanders of each side increasingly wary of sending out their fleets unless (a highly unlikely condition) the enemy’s ships were known to be approaching one’s own shoreline. Given this impotence in surface warfare, the Central Powers gradually turned to U-boat attacks upon Allied merchantmen, which was a much more serious threat; but by its very nature, a submarine campaign against trade was a slow, grinding affair, the real success of which could be

measured only by setting the tonnage of merchant ships lost against the tonnage being launched in Allied shipyards—and that against the number of U-boats destroyed. It was not a form of war which promised swift victories.

199

A second reason for the relative impotence of the Allies’ numerical and industrial superiority lay in the nature of the military struggle itself. When each side possessed millions of troops sprawling across hundreds of miles of territory, it was difficult (in western Europe, impossible) to achieve a single decisive victory in the manner of Jena or Sadowa; even a “big push,” methodically plotted and prepared for months ahead, usually disintegrated into hundreds of small-scale battlefield actions, and was usually also accompanied by a near-total breakdown in communications. While the front line might sway back and forth in certain sections, the absence of the means to achieve a real breakthrough allowed each side to mobilize and bring up reserves, fresh stocks of shells, barbed wire, and artillery in time for the next stalemated clash. Until late in the war, no army was able to discover how to get its own troops through enemy-held defenses often

four miles deep

, without either exposing them to withering counterfire or so churning up the ground by earlier bombardments that it was difficult to advance. Even when an occasional surprise assault overran the first few lines of enemy trenches, there was no special equipment to exploit that advantage; the railway lines were miles in the rear, the cavalry was too vulnerable (and tied to fodder supplies), heavily laden infantrymen could not move far, and the vital artillery arm was restricted by its long train of horse-drawn supply wagons.

200