The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (54 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

Yet this top-heavy concentration upon armaments output—increasing machine-gun production 170-fold, and rifle production 290-fold—could never have been achieved had France not been able to rely upon British and American aid, which came in the form of a steady flow of imported coal, coke, pig iron, steel, and machine tools so vital for the

new munitions industry; in the Anglo-American loans of over $3.6 billion, so that France could pay for raw materials from overseas; in the allocation of increasing amounts of British shipping, without which most of this movement of goods could not have been carried out; and in the supply of foodstuffs. This last-named category seems a curious defect in a country which in peacetime always produced an agricultural surplus; but the fact was that the French, like the other European belligerents (except Britain), hurt their own agriculture by taking too many men from the land, diverting horses to the cavalry or to army-transport duties, and investing in explosives and artillery to the detriment of fertilizer and farm machinery. In 1917, a bad harvest year, food was scarce, prices were spiraling ominously upward, and the French army’s own stock of grain was reduced to a two-day supply—a potentially revolutionary situation (especially following the mutinies), which was only averted by the emergency allocation of British ships to bring in American grain.

214

In rather the same way, France needed to rely upon increasing amounts of British and, later, American

military

assistance along the western front. For the first two to three years of the war, it bore the brunt of that fighting and took appalling casualties—over 3 million even before Nivelle’s offensive of 1917; and since it had not the vast reserves of untrained manpower which Germany, Russia, and the British Empire possessed, it was far harder to replace such losses. By 1916–1917, however, Haig’s army on the western front had been expanded to two-thirds the size of the French army and was holding over eighty miles of the line; and although the British high command was keen to go on the offensive in any case, there is no doubt that the Somme campaign helped to ease the pressure upon Verdun—just as Passchendaele in 1917 took the German energies away from the French part of the front while Pétain was desperately attempting to rebuild his forces’ morale after the mutinies, and waiting for the new trucks, aircraft, and heavy artillery to do the work which massed infantry clearly could not. Finally, in the epic to-and-fro battles along the western front between March and August 1918, France could rely not only upon British and imperial divisions, but also upon increasing numbers of American ones. And when Foch orchestrated his final counteroffensive in September 1918, he could engage the 197 under-strength German divisions with 102 French, 60 British Empire, 42 (double-sized) American, and 12 Belgian divisions.

215

Only with a

combination

of armies could the formidable Germans at last be driven from French soil and the country be free again.

When the British entered the war in August 1914, it was with no sense that they, too, would become dependent upon another Great Power in order to secure ultimate victory. So far as can be deduced from their prewar plans and preparations, the strategists had imagined

that while the Royal Navy was sweeping German merchantmen (and perhaps the High Seas Fleet) from the oceans, and while the German colonial empire was being seized by dominion and British Indian troops, a small but vital expeditionary force would be sent across the Channel to “plug” a gap between the French and Belgian armies and to hold the German offensive until such time as the Russian steamroller and the French Plan XVII were driving deep into the Fatherland. The British, like all the other powers, were not prepared for a long war, although they had taken certain measures to avoid a sudden crisis in their delicate international credit and commercial networks. But unlike the others, they were also not prepared for large-scale operations on the continent of Europe.

216

It was therefore scarcely surprising that one to two years of intense preparation were needed before 1 million British troops stood ready in France, and that the explosion of government spending upon rifles, artillery, machine guns, aircraft, trucks, and ammunition merely revealed innumerable production deficiencies which were only slowly corrected by Lloyd George’s Ministry of Munitions.

217

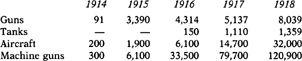

Here again there were fantastic rises in output, as shown in

Table 23

.

Table 23

. U

.K. Munitions Production, 1914–1918

218

But that is scarcely surprising when one realizes that British defense expenditures rose from £91 million in 1913 to £1.956 billion in 1918, by which time it represented 80 percent of total government expenditures and 52 percent of the GNP.

219

To give full details of the vast growth in the number of British and imperial divisions, squadrons of aircraft, and batteries of heavy artillery seems less important, therefore, than to point to the weaknesses which the First World War exposed in Britain’s overall strategical position. The first was that while geography and the Grand Fleet’s numerical superiority meant the Allies retained command of the sea in the

surface

conflict, the Royal Navy was quite unprepared to counter the unrestricted U-boat warfare which the Germans were implementing by early 1917. The second was that whereas the cluster of relatively cheap strategical weapons (blockade, colonial campaigns, amphibious operations) did not seem to be working against a foe with the wide-ranging resources of the Central Powers, the alternative strategy of direct military encounters with the German army also seemed incapable of producing results—and was fearfully costly in manpower. By the

time the Somme campaign whimpered to a close in November 1916, British casualties in that fighting had risen to over 400,000. Although this wiped out the finest of Britain’s volunteers and shocked the politicians, it did not dampen Haig’s confidence in ultimate victory. By the middle of 1917 he was preparing for yet a further offensive from Ypres northeastward to Passchendaele—a muddy nightmare which cost another 300,000 casualties and badly hurt morale throughout much of the army in France. It was, therefore, all too predictable that however much Generals Haig and Robertson protested, Lloyd George and the imperialist-minded War Cabinet were tempted to divert ever more British divisions to the Near East, where substantial territorial gains beckoned and losses were far fewer than would be incurred in storming well-held German trenches.

220

Even before Passchendaele, however, Britain had assumed (despite this imperial campaigning) the leadership role in the struggle against Germany. France and Russia might still have larger armies in the field, but they were exhausted by Nivelle’s costly assaults and by the German counterblow to the Brusilov offensive. This leadership role was even more pronounced at the economic level, where Britain functioned as the banker and loan-raiser on the world’s credit markets, not only for itself but also by guaranteeing the monies borrowed by Russia, Italy, and even France—since none of the Allies could provide from their own gold or foreign-investment holdings anywhere near the sums required to pay the vast surge of imported munitions and raw materials from overseas. By April 1, 1917, indeed, inter-Allied war credits had risen to $4.3 billion, 88 percent of which was covered by the British government. Although this looked like a repetition of Britain’s eighteenth-century role as “banker to the coalition,” there was now one critical difference: the sheer size of the trade deficit with the United States, which was supplying billions of dollars’ worth of munitions and foodstuffs to the Allies (but not, because of the naval blockade, to the Central Powers) yet required few goods in return. Neither the transfer of gold nor the sale of Britain’s enormous dollar securities could close this gap; only borrowing on the New York and Chicago money markets, to pay the American munitions suppliers in dollars, would do the trick. This in turn meant that the Allies became ever more dependent upon U.S. financial aid to sustain their own war effort. In October 1916, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer was warning that “by next June, or earlier, the President of the American Republic would be in a position, if he wishes, to dictate his terms to us.”

221

It was an altogether alarming position for “independent” Great Powers to be in.

But what of Germany? Its performance in the war had been staggering. As Professor Northedge points out, “with no considerable assistance from her allies, [it] had held the rest of the world at bay, had beaten Russia, had driven France, the military colossus of Europe for

more than two centuries, to the end of her tether, and in 1917, had come within an ace of starving Britain into surrender.”

222

Part of this was due to those advantages outlined above: good inner lines of communication, easily defensible positions in the west, and open space for mobile warfare against less efficient foes in the east. It was also due to the sheer fighting quality of the German forces, which possessed an array of intelligent, probing staff officers who readjusted to the new conditions of combat faster than those in any other army, and who by 1916 had rethought the nature of both defensive and offensive warfare.

223

Finally, the German state could draw upon both a large population and a massive industrial base for the prosecution of “total war.” Indeed, it actually mobilized more men than Russia—13.25 million to 13 million—a remarkable achievement in view of their respective overall populations; and always had more divisions in the field than Russia. Its own munitions production soared, under the watchful eye not only of the high command but of intelligent bureaucrat-businessmen such as Walther Rathenau, who set up cartels to allocate vital supplies and avoid bottlenecks. Adept chemists produced ersatz goods for those items (e.g., Chilean nitrates) cut off by the British naval blockade. The occupied lands of Luxembourg and northern France were exploited for their ores and coal, Belgian workers were drafted into German factories, Rumanian wheat and oil were systematically plundered following the 1916 invasion. Like Napoleon and Hitler, the German military leadership sought to make conquest pay.

224

By the first half of 1917, with Russia collapsing, France wilting, and Britain under the “counterblockade” of the U-boats, Germany seemed on the brink of victory. Despite all the rhetoric of “fighting to the bitter end,” statesmen in London and Paris were going to be anxiously considering the possibilities of a compromise peace for the next twelve months until the tide turned.

225

Yet behind this appearance of Teutonic military-industrial might, there lurked very considerable problems. These were not too evident before the summer of 1916, that is, while the German army stayed on the defensive in the west and made sweeping strikes in the east. But the campaigns of Verdun and the Somme were of a new order of magnitude, both in the firepower employed and the losses sustained; and German casualties on the western front, which had been around 850,000 in 1915, leaped to nearly 1.2 million in 1916. The Somme offensive in particular impressed the Germans, since it showed that the British were at last making an all-out commitment of national resources for victory in the field; and it led in turn to the so-called Hindenburg Program of August 1916, which proclaimed an enormous expansion in munitions production and a far tighter degree of controls over the German economy and society to meet the demands of total

war. This combination of on the one hand an authoritarian regime exercising all sorts of powers over the population and on the other a great growth in government borrowing and printing of paper money rather than raising income and dividend taxes—which, in turn, produced high inflation—dealt a heavy blow to popular morale—an ingredient in grand strategy which Ludendorff was far less equipped to understand than, say, a politician like Lloyd George or Clemenceau.

Even as an economic measure, the Hindenburg Program had its problems. The announcement of quite fantastic production totals—doubling explosives output, trebling machine-gun output—led to all sorts of bottlenecks as German industry struggled to meet these demands. It required not only many additional workers, but also a massive infrastructural investment, from new blast furnaces to bridges over the Rhine, which further used up labor and resources. Within a short while, therefore, it became clear that the program could be achieved only if skilled workers were returned from military duty; accordingly, 1.2 million were released in September 1916, and a further 1.9 million in July 1917. Given the serious losses on the western front, and the still-considerable casualties in the east, such withdrawals meant that even Germany’s large able-bodied male population was being stretched to its limits. In that respect, although Passchendaele was a catastrophe for the British army, it was also viewed as a disaster by Ludendorff, who saw another 400,000 of his troops incapacitated. By December 1917, the German army’s manpower totals were consistently under the peak of 5.38 million men it had possessed six months earlier.

226