The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (49 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

The mobilization and deployment problem was exacerbated by the almost insuperable difficulty caused by Russia’s commitments to France and Serbia. Given the country’s less efficient railway system and the vulnerability of the forces deployed in the Polish salient to a possible “pincer” attack from East Prussia and Galicia, it had seemed prudent prior to 1900 for the Russian high command to stay on the defensive at the outset of war and steadily to build up its military strength; and, indeed, some strategists still argued that case in 1912. Many more generals, however, were keen to smash Austria-Hungary (against which they were confident of victory) and, as the tension between Vienna and Belgrade mounted, to help the latter in the event of an Austro-Hungarian invasion of Serbia. Yet for Russia to concentrate its forces on the southern front was made impossible by the fear of what Germany might do. For decades after 1871, the planners had assumed that a Russo-German war would begin with a massive and swift German assault eastward. But when the outlines of the Schlieffen Plan became clear, St. Petersburg came under enormous French pressure to launch offensives against Germany

as soon as it could

, in order to relieve its western ally. Fear of having France eliminated, together with Paris’s tough insistence that further loans be tied to improvements in Russia’s

offensive

capabilities, compelled the Russian planners to agree to strike westward as quickly as possible. All this had caused enormous wrangles within the general staff in the few years before 1914, with the various schools of thought disagreeing over the number of army corps to be deployed on the northern as opposed to

the southern front, over the razing of the old defensive fortresses in Poland (in which, absurdly, so much of the new artillery was sited), and over the feasibility of ordering a partial rather than a complete mobilization. Given Russia’s diplomatic obligations, the ambivalence was perhaps understandable; but it did not help the cause of producing a smoothly run military machine which would secure swift victories against its foes.

150

This catalogue of problems could be extended almost ad nauseam. The fifty divisions of Russian cavalry, thought vital in a country with few modern roads, required so much fodder—there were about one million horses!—that they alone would probably produce a breakdown in the railway system; supplying hay would certainly slow down any sustained offensive operation, or even the movement of reserves. Because of the backwardness of its transport system and the internal-policing roles of the military, literally millions of its soldiers in wartime would not be considered front-line troops at all. And although the sums of money allocated to the army prior to 1914 seemed enormous, much of it was consumed by the basic needs of food, clothing, and fodder. Similarily, despite the large-scale increases in the fleet and the fact that many of the new designs have been described as “excellent,”

151

the navy required a much higher level of technical training as well as more frequent tactical practice among its personnel to be truly effective; since it had neither (the crews were still based mainly on shore) and was forced to divide its fleet between the Baltic and the Black Sea, the prospects for Russian sea power were not good—unless it fought only the Turks.

Finally, no assessment of Russia’s overall capacities in this period can avoid some comments upon the regime itself. Although certain foreign conservatives admired its autocratic and centralized system, arguing that it gave a greater consistency and strength to national policies than the western democracies were capable of, a closer examination would have revealed innumerable flaws. Czar Nicholas II was a Potemkin village in person, simple-minded, reclusive, disliking difficult decisions, and blindly convinced of his sacred relationship with the Russian people (in whose real welfare, of course, he showed no interest). The methods of governmental decision-making at the higher levels were enough to give “Byzantinism” a bad name: irresponsible grand dukes, the emotionally unbalanced empress, reactionary generals, and corrupt speculators, outweighing by far the number of diligent and intelligent ministers whom the regime could recruit and who, only occasionally, could reach the czar’s ear. The lack of consultation and understanding between, say, the foreign ministry and the military was at times frightening. The court’s attitude to the assembly (the Duma) was one of unconcealed contempt. Achieving radical reforms in this atmosphere was impossible, when the aristocracy cared only for its

privileges and the czar cared only for his peace of mind. Here was an elite in constant fear of workers’ and peasants’ unrest, and yet, although government spending was by far the largest in the world in absolute terms, it kept direct taxes on the rich to a minimum (6 percent of the state’s revenue) and placed massive burdens upon foodstuffs and vodka (about 40 percent). Here was a country with a delicate balance of payments, but with no chance of preventing (or taxing) the vast outflow of monies which Russian aristocrats spent abroad. Partly because of the traditions of heavy-handed autocracy, partly because of the inordinately flawed class system, and partly because of the low levels of education and pay, Russia lacked those cadres of competent civil servants who made, for example, the German, British, and Japanese administrative systems

work

. Russia was not, in reality, a strong state; and it was still one which, given the drift in leadership, was capable of blundering unprepared into foreign complications, notwithstanding the lessons of 1904.

How then, are we to assess the real power of Russia in these years? That it was growing in both industrial and military terms year by year was undoubted. That it possessed many other strengths—the size of its army, the patriotism and sense of destiny in certain classes of society, the near-invulnerability of its Muscovite heartland—was also true. Against Austria-Hungary, against Turkey, perhaps now even against Japan, it had good prospects of fighting and winning. But the awful thing was that its looming clash with Germany was coming too early for Russia to deal with. “Give the state twenty years of internal and external peace,” boasted Stolypin in 1909, “and you will not recognize Russia.” That

may

have been true, even if Germany’s strength was also likely to increase over the same period. Yet according to the data produced by Professors Doran and Parsons (

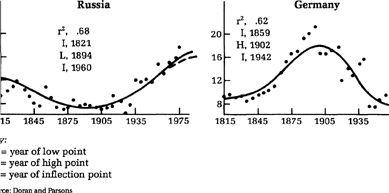

see Chart 1

), the “relative power” of Russia in these decades was just rising from its low point after 1894 whereas Germany’s was close to its peak.

152

And while that may be too schematized a presentation to most readers, it had indeed been true (as mentioned previously) that Russia’s power and influence had declined throughout much of the nineteenth century in rough proportion to her increasing economic backwardness. Every major exposure to battle (the Crimean War, the Russo-Japanese War) had revealed both new and old military weaknesses, and compelled the regime to endeavor to close the gap which had opened up between Russia and the western nations. In the years before 1914, it seemed to some observers that the gap was again being closed, although to others manifold weaknesses still remained. Since it could not have Stolypin’s required two decades of peace, it would once again have to pass through the test of war to see if it had recovered the position in European power politics which it possessed in 1815 and 1848.

Chart 1. The Relative Power of Russia and Germany

Of all the changes which were taking place in the global power balances during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there can be no doubt that the most decisive one for the future was the growth of the United States. With the Civil War over, the United States was able to exploit the many advantages mentioned previously—rich agricultural land, vast raw materials, and the marvelously convenient evolution of modern technology (railways, the steam engine, mining equipment) to develop such resources; the lack of social and geographical constraints; the absence of significant foreign dangers; the flow of foreign and, increasingly, domestic investment capital—to transform itself at a stunning pace. Between the ending of the Civil War in 1865 and the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898, for example, American wheat production increased by 256 percent, corn by 222 percent, refined sugar by 460 percent, coal by 800 percent, steel rails by 523 percent, and the miles of railway track in operation by over 567 percent. “In newer industries the growth, starting from near zero, was so great as to make percentages meaningless. Thus the production of crude petroleum rose from about 3,000,000 barrels in 1865 to over 55,000,000 barrels in 1898 and that of steel ingots and castings from less than 20,000 long tons to nearly 9,000,000 long tons.”

153

This was not a growth which stopped with the war against Spain; on the contrary, it rose upward at the same meteoric pace throughout the early twentieth century. Indeed, given the advantages listed above, there was a virtual inevitability to the whole process. That is to say, only persistent human ineptitude, or near-constant civil war, or a climatic disaster could have checked this expansion—or deterred the millions of immigrants

who flowed across the Atlantic to get their share of the pot of gold and to swell the productive labor force.

The United States seemed to have

all

the economic advantages which

some

of the other powers possessed

in part

, but

none

of their disadvantages. It was immense, but the vast distances were shortened by some 250,000 miles of railway in 1914 (compared with Russia’s 46,000 miles, spread over an area two and a half times as large). Its agricultural yields per acre were always superior to Russia’s; and if they were never as large as those of the intensively farmed regions of western Europe, the sheer size of the area under cultivation, the efficiency of its farm machinery, and the decreasing costs of transport (because of railways and steamships) made American wheat, corn, pork, beef, and other products cheaper than any in Europe. Technologically, leading American firms like International Harvester, Singer, Du Pont, Bell, Colt, and Standard Oil were equal to, or often better than, any in the world; and they enjoyed an enormous domestic market and economies of scale, which their German, British, and Swiss rivals did not. “Gigantism” in Russia was not a good indicator of industrial efficiency;

154

in the United States, it usually was. For example, “Andrew Carnegie was producing more steel than the whole of England put together when he sold out in 1901 to J. P. Morgan’s colossal organization, the United States Steel Corporation.”

155

When the famous British warship designer Sir William White made a tour of the United States in 1904, he was shaken to discover fourteen battleships and thirteen armored cruisers being built simultaneously in American yards (although, curiously, the U.S. merchant marine remained small). In industry

and

agriculture

and

communications, there was both efficiency and size. It was therefore not surprising that U.S. national income, in absolute figures and per capita, was so far above everybody else’s by 1914.

156

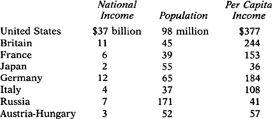

Table

21.

National Income, Population, and per Capita Income of the Powers in 1914

The consequences of this rapid expansion are reflected in

Table 21

, and in the pertinent comparative statistics. In 1914, the United States

was producing 455 million tons of coal, well ahead of Britain’s 292 million and Germany’s 277 million. It was the largest oil producer in the world, and the greatest consumer of copper. Its pig-iron production was larger than those of the next three countries (Germany, Britain, France) combined, and its steel production almost equal

157

to the next four countries (Germany, Britain, Russia, and France). Its energy consumption from modern fuels in 1913 was equal to that of Britain, Germany, France, Russia, and Austria-Hungary together. It produced, and possessed, more motor vehicles than the rest of the world together. It was, in fact an entire rival continent and growing so fast that it was coming close to the point of overtaking all of Europe. According to one calculation, indeed, had these growth rates continued and a world war been avoided, the United States would have overtaken Europe as the region possessing the greatest economic output in the world by 1925.

158

What the First World War did, through the economic losses and dislocations suffered by the older Great Powers, was to bring that time forward, by six years, to 1919.

159

The “Vasco da Gama era”—the four centuries of European dominance in the world—was coming to an end even before the cataclysm of 1914.