The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (46 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

And yet the French army went into battle in 1914 confident of victory, having dropped its defensive strategy in favor of an all-out offensive, reflecting the heightened emphasis upon morale which Grandmaison and others attempted to inculcate into the army—psychologically, one suspects, as compensation for these very material weaknesses. “Neither numbers nor miraculous machines will determine victory,” General Messing preached. “This will go to soldiers with valor and quality—and by this I mean superior physical and moral endurance, offensive strength.”

98

This assertiveness was associated with the “patriotic revival” in France which took place after the 1911

Moroccan crisis and which suggested the country would fight far better than it had in 1870, despite the class and political divisions which had made it appear so vulnerable during the Dreyfus affair. Most military experts assumed that the war to come would be short. What mattered, therefore, was the number of divisions which could immediately be put into the field, not the size of the German steel and chemical industries nor the millions of potential recruits Germany possessed.

99

This revival of national confidence was perhaps most strongly affected by the improvement in France’s international position secured by the foreign minister, Delcassé, and his diplomats after the turn of the century.

100

Not only had they nursed and maintained the vital link to St. Petersburg despite all the diplomatic efforts of the Kaiser’s government to weaken it, but they had steadily improved relations with Italy, virtually detaching it from the Triple Alliance (and thus easing the strategical problem of having to fight in Savoy as well as Lorraine). Most important of all, the French had been able to compose their colonial differences with Britain in the 1904

entente

, and then to convince leading members of the Liberal government in London that France’s security was a British national interest. Although domestic-political reasons in Britain precluded a fixed alliance, the chances of France obtaining future British support improved with each addition to Germany’s High Seas Fleet and with every indication that a German strike westward would go through neutral Belgium. If Britain did come in, the Germans would have to worry not only about Russia but about the effect of the Royal Navy on its High Seas Fleet, the destruction of its overseas trade, and a small but significant British expeditionary force deployed in northern France. Fighting the Boches with Russia and Britain as one’s allies had been the French dream since 1871; now it seemed a distinct reality.

France was not strong enough to oppose Germany in a one-to-one struggle, something which all French governments were determined to avoid. If the mark of a Great Power is a country which is willing and able to take on any other, then France (like Austria-Hungary) had slipped to a lower position. But that definition seemed too abstract in 1914 to a nation which felt psychologically geared up for war,

101

militarily stronger than ever, wealthy, and, above all, endowed with powerful allies. Whether even a combination of all those features would enable France to withstand Germany was an open question; but most Frenchmen seemed to think it would.

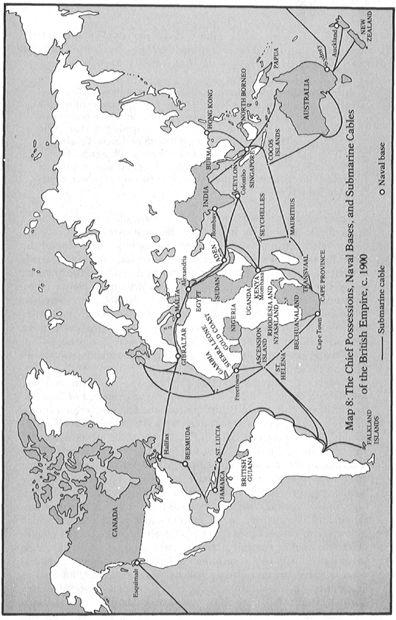

At first sight, Britain was imposing. In 1900 it possessed the largest empire the world had ever seen, some twelve million square miles of land and perhaps a quarter of the population of the globe. In the preceding three decades alone, it had added 4.25 million square miles

and 66 million people to the empire. It was not simply a critical later historian but also the French and the Germans, the Ashanti and the Burmese, and many others at the time, who felt as follows:

There had taken place, in the half-century or so before the [1914] war, a tremendous expansion of British power, accompanied by a pronounced lack of sympathy for any similar ambition on the part of other nations.… If any nation had truly made a bid for world power, it was Great Britain. In fact, it had more than made a bid for it. It had achieved it. The Germans were merely talking about building a railway to Bagdad. The Queen of England was Empress of India. If any nation had upset the world’s balance of power, it was Great Britain.

102

There were other indicators of British strength: the vast increases in the Royal Navy, equal in power to the next two largest fleets; the unparalleled network of naval bases and cable stations around the globe; the world’s largest merchant marine by far, carrying the goods of what was still the world’s greatest trading nation; and the financial services of the City of London, which made Britain the biggest investor, banker, insurer, and commodity dealer in the global economy. The crowds who cheered their heads off during Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee festivities in 1897 had some reason to be proud. Whenever the three or four world empires of the coming century were discussed, it—but not France, or Austria-Hungary, or many other candidates—was always on the short list of members.

However, if viewed from other perspectives—say, from the sober calculations of the British “official mind,”

103

or from that of later historians of the collapse of British power—the late nineteenth century was certainly not a time when the empire was making a “bid for world power.” On the contrary, that “bid” had been made a century earlier and had climaxed in the 1815 victory, which allowed the country to luxuriate in the consequent half-century of virtually unchallenged maritime and imperial preeminence. After 1870, however, the shifting balance of world forces was eroding British supremacy in two ominous and interacting ways. The first was that the spread of industrialization and the changes in the military and naval weights which followed from it weakened the relative position of the British Empire more than that of any other country, because it was

the

established Great Power, with less to gain than to lose from fundamental alterations in the status quo. Britain had not been as directly affected as France and Austria-Hungary by the emergence of a powerful, united Germany (only after 1904–1905 would London really have to grapple with that issue). But it was

the

state most impinged upon by the rise of American power, since British interests (Canada, naval bases in the

Caribbean, trade and investment in Latin America) were much more prominent in the western hemisphere than those of any other European country;

104

it was

the

country most affected by the expansion of Russian borders and strategic railways in Turkestan, since everyone could see the threat which that posed to British influence in the Near East and Persian Gulf, and ultimately perhaps to its control of the Indian subcontinent;

105

it was

the

country which, by enjoying the greatest share of China’s foreign trade, was likely to have its commercial interests the most seriously damaged by a carving up of the Celestial Empire or by the emergence of a new force in that region;

106

similarly, it was

the

power whose relative position in Africa and the Pacific was affected the most by the post-1880 scramble for colonies, since it had (in Hobsbawm’s phrase) “exchanged the informal empire over most of the underdeveloped world for the formal empire of a quarter of it”

107

—which was not a good bargain, despite the continued array of fresh acquisitions to Queen Victoria’s dominions.

While some of these problems (in Africa or China) were fairly new, others (the rivalry with Russia in Asia, and with the United States in the western hemisphere) had exercised many earlier British administrations. What was different now was that the relative power of the various challenger states was much greater, while the threats seemed to be developing almost simultaneously. Just as the Austro-Hungarian Empire was distracted by having to grapple with a number of enemies within Europe, so British statesmen had to engage in a diplomatic and strategical juggling act that was literally worldwide in its dimensions. In the critical year of 1895, for example, the Cabinet found itself worrying about the possible breakup of China following the Sino-Japanese War, about the collapse of the Ottoman Empire as a result of the Armenian crisis, about the looming clash with Germany over southern Africa at almost exactly the same time as the quarrel with the United States over the Venezuela-British Guiana borders, about French military expeditions in equatorial Africa, and about a Russian drive toward the Hindu Kush.

108

It was a juggling act which had to be carried out in naval terms as well; for no matter how regularly the Royal Navy’s budget was increased, it could no longer “rule the waves” in the face of the five or six foreign fleets which were building in the 1890s, as it had been able to do in midcentury. As the Admiralty repeatedly pointed out, it

could

meet the American challenge in the western hemisphere, but only by diverting warships from European waters, just as it

could

increase the size of the Royal Navy in the Far East, but only by weakening its squadrons in the Mediterranean. It could not be strong everywhere. Finally, it was a juggling act which had to be carried out in military terms, by the transfer of battalions from Aldershot to Cairo, or from India to Hong Kong, to meet the latest emergencies—and yet all this had to be done by a small-scale volunteer force that had

been completely eclipsed by mass armies on the Prussian model.

109

The second, interacting weakness was less immediate and dramatic, but perhaps even more serious. It was the erosion of Britain’s industrial and commercial preeminence, upon which, in the last resort, its naval, military, and imperial strength rested. Established British industries such as coal, textiles, and ironware increased their output in absolute terms in these decades, but their relative share of world production steadily diminished; and in the newer and increasingly more important industries such as steel, chemicals, machine tools, and electrical goods, Britain soon lost what early lead it possessed. Industrial production, which had grown at an annual rule of about 4 percent in the period 1820 to 1840 and about 3 percent between 1840 and 1870, became more sluggish; between 1875 and 1894 it grew at just over 1.5 percent annually, far less than that of the country’s chief rivals. This loss of industrial supremacy was soon felt in the cutthroat competition for customers. At first, British exports were priced out of their favorable position in the industrialized European and North American markets, often protected by high tariff barriers, and then out of certain colonial markets, where other powers competed both commercially and by placing tariffs around their new annexations; and, finally, British industry found itself weakened by an ever-rising tide of imported foreign manufacturers into the unprotected home market—the clearest sign that the country was becoming uncompetitive.

The slowdown of British productivity and the decrease in competitiveness in the late nineteenth century has been one of the most investigated issues in economic history.

110

It involved such complex issues as national character, generational differences, the social ethos, and the educational system as well as more specific economic reasons like low investment, out-of-date plant, bad labor relations, poor salesmanship, and the rest. For the student of grand strategy, concerned with the

relative

picture, these explanations are less important than the fact that the country as a whole was steadily losing ground. Whereas in 1880 the United Kingdom still contained 22.9 percent of total world manufacturing output, that figure had shrunk to 13.6 percent by 1913; and while its share of world trade was 23.2 percent in 1880, it was only 14.1 percent in 1911–1913. In terms of industrial muscle, both the United States and imperial Germany had moved ahead. The “workshop of the world” was now in third place, not because it wasn’t growing, but because others were growing faster.

Nothing frightened the thinking British imperialists more than this relative economic decline, simply because of its impact upon British

power

. “Suppose an industry which is threatened [by foreign competition] is one which lies at the very root of your system of National defence, where are you then?” asked Professor W.A.S. Hewins in 1904. “You could not get on without an iron industry, a great Engineering

trade, because in modern warfare you would not have the means of producing, and maintaining in a state of efficiency, your fleets and armies.”

111

Compared with this development, quarrels over colonial borders in West Africa or over the future of the Samoan Islands were trivial. Hence the imperialists’ interests in tariff reform—abandoning the precepts of free trade in order to protect British industries—and in closer ties with the white dominions, in order to secure both defense contributions and an exclusive imperial market. Britain had now become, in Joseph Chamberlain’s frightening phrase, “the weary Titan, [staggering] under the too vast orb of its fate.”

112

In the years to come, the First Lord of the Admiralty warned, “the United Kingdom by itself will not be strong enough to hold its proper place alongside of the U.S., or Russia, and probably not Germany. We shall be thrust aside by sheer weight.”

113