The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (41 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

But perhaps the best measure of a nation’s industrialization is its

energy consumption from modern forms (that is, coal, petroleum, natural gas, and hydroelectricity, but not wood), since it is an indication both of a country’s technical capacity to exploit inanimate forms of energy and of its economic pulse rate; these figures are given in

Table 16

.

Table 13. Urban Population of the Powers (in millions) and as Percentage of the Total Population, 1890-1938

19

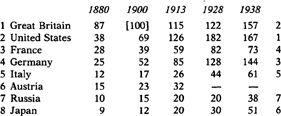

Table 14. Per Capita Levels of Industrialization, 1880–1938

20

(relative to G.B. in 1900 = 100)

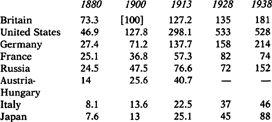

Table 15. Iron/Steel Production of the Powers, 1890-1938

21

(millions of tons; pig-iron production for 1890, steel thereafter)

Table 16. Energy Consumption of the Powers, 1890–1938

22

(in millions of metric tons of coal equivalent)

Tables 15

and

16

both confirm the swift industrial changes which occurred in

absolute

terms to some of the powers in particular periods—Germany before 1914, Russia and Japan in the 1930s—as well as indicating the slower rates of growth in Britain, France and Italy. This can also be represented in

relative terms

to indicate a country’s comparative industrial position over time (

Table 17

).

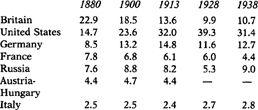

Table 17. Total Industrial Potential of the Powers in Relative Perspective, 1880–1938

23

(U.K. in 1900 = 100)

Finally, it is useful to return in

Table 18

to Bairoch’s figures on shares of world manufacturing production to show the changes which occurred since the earlier analysis of the nineteenth-century balances in the preceding chapter.

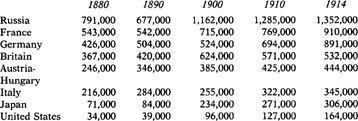

Table 18. Relative Shares of World Manufacturing Output, 1880-1938

24

(percent)

In the face of such unnervingly specific figures, that a certain power possessed 2.7 percent of world manufacturing production in 1913, or that another had an industrial potential in 1928 which was only 45 percent of Britain’s in 1900, it is worth reemphasizing that all these statistics are abstract until placed within a specific historical and geopolitical context. Countries with virtually identical industrial output might nonetheless merit substantially different ratings in terms of Great Power effectiveness, because of such factors as the internal cohesion of the society in question, its ability to mobilize resources for state action, its geopolitical position, and its diplomatic capacities. Given the limitations of space, it will not be possible in this chapter to do for all the Great Powers what Correlli Barnett sought to do in his large-scale study of Britain some years ago. But what follows will try to remain close to Barnett’s larger framework, in which he argues that

the power of a nation-state by no means consists only in its armed forces, but also in its economic and technological resources; in the dexterity, foresight and resolution with which its foreign policy is conducted; in the efficiency of its social and political organization. It consists most of all in the nation itself, the people; their skills, energy, ambition, discipline, initiative; their beliefs, myths and illusions. And it consists, further, in the way all these factors are related to one another. Moreover national power has to be considered not only in itself, in its absolute extent, but relative to the state’s foreign or imperial obligations; it has to be considered relative to the power of other states.

25

There is perhaps no better way of illustrating the diversity of grand-strategical effectiveness than by looking in the first instance at the three relative newcomers to the international system, Italy, Germany, and Japan. The first two had become united states only in 1870–1871;

the third began to emerge from its self-imposed isolation after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. In all three societies there were impulses to emulate the established powers. By the 1880s and 1890s each was acquiring overseas territories; each, too, began to build a modern fleet to complement its standing army. Each was a significant element in the diplomatic calculus of the age and, at the latest by 1902, had become an alliance-partner to an older power. Yet all these similarities can hardly outweigh the fundamental differences in real strength which each possessed.

At first sight, the coming of a united Italian nation represented a major shift in the European balances. Instead of being a cluster of rivaling small states, partly under foreign sovereignty and always under the threat of foreign intervention, there was now a solid block of thirty million people growing so swiftly that it was coming close to France’s total population by 1914. Its army and its navy in this period were not especially large, but as

Tables 19

and

20

show, they were still very respectable.

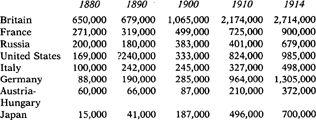

Table 19. Military and Naval Personnel of the Powers, 1880–1914

26

Table 20. Warship Tonnage of the Powers, 1880–1914

27

In diplomatic terms, as was noted above,

28

the rise of Italy certainly impinged upon its two Great Power neighbors, France and Austria-Hungary; and while its entry into the Triple Alliance in 1882 ostensibly

“resolved” the Italo-Austrian rivalry, it confirmed that an isolated France faced foes on two fronts. Within just over a decade from its unification, therefore, Italy seemed a full member of the European Great Power system, and Rome ranked alongside the other major capitals (London, Paris, Berlin, St. Petersburg, Vienna, Constantinople) as a place to which full embassies were accredited.