The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (36 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

But the Russian army was even worse off. The ordinary infantryman fought well, and, under the inspired leadership of Admiral Nakhimov and the engineering genius of Colonel Todtleben, Russia’s prolonged defense of Sevastopol was a remarkable feat. But in all other respects the army was woefully inadequate. The cavalry regiments were unadventurous and their parade-ground horses incapable of strenuous campaigning (here the irregular cossack forces were better). Worse still, the Russian soldiers were wretchedly armed. Their old-fashioned flintlock muskets had a range of 200 yards, whereas the rifles of the Allied troops could fire effectively up to 1,000 yards; thus Russian casualties were far heavier.

Worst of all, even when the hugeness of the task was known, the Russian system

as a whole

was incapable of responding to it. Army leadership was poor, ridden with personal rivalries, and never able to produce a coherent grand strategy—here it simply reflected the general incompetence of the czar’s government. There were very few trained and educated officers of the middle rank, such as the Prussian army possessed in abundance, and initiative was totally frowned upon. Astonishingly, there were also very few reservists to call up in the event

of a national emergency, since the adoption of a mass short-service system would have involved the demise of serfdom.

*

One consequence of this system was that Russia’s long-service army included many

over-aged

troopers; another even more fatal consequence was that some 400,000 of the new recruits hastily enrolled at the beginning of the war were totally untrained—for there were insufficient officers to do the job—and the withdrawal of that many men from the serf labor market hurt the Russian economy.

Finally, there were the logistical and economic weaknesses. Since there were no railways south of Moscow (!), the horse-drawn supply wagons had to cross hundreds of miles of steppes, which were a sea of mud during the spring thaw and the autumn rains. Furthermore, the horses themselves required so much fodder (which in turn had to be carried by other packhorses, and so on) that an enormous logistical effort produced disproportionately small results: allied troops and reinforcements could be sent from France and England by sea to the Crimea in three weeks, whereas Russian troops from Moscow sometimes took three months to reach the front. More alarming still was the collapse of the Russian army’s equipment stocks. “At the beginning of the war 1 million guns had been stockpiled; [at the end of 1855] only 90,000 were left. Of the 1,656 field guns, only 253 were available.… Stocks of powder and shot were in even worse shape.”

68

The longer the war lasted, the greater the allied superiority became, while the British blockade stifled the importation of new weapons.

But the blockade did more than that: it cut off Russia’s flow of grain and other exports (except for those going overland to Prussia) and made it impossible for the Russian government to pay for the war other than by heavy borrowing. Military expenditures, which even in peacetime took four-fifths of the state revenue, rose from about 220 million rubles in 1853 to about 500 million in both war years 1854 and 1855. To cover part of the alarming deficit, the Russian treasury borrowed in Berlin and Amsterdam, but then the ruble’s international value tumbled; to cover the rest, it resorted to printing paper money, which led to large-scale price inflation and increasing peasant unrest. The earlier, brave attempts of the finance ministry to create a silver-based ruble and to ban all promissory notes—which had been the ruination of “sound finance” during the Napoleonic War and the campaigns against Persia, Turkey, and the Polish rebels—were now completely wrecked by the war in the Crimea. If Russia persisted in its fruitless struggle, the Crown Council was warned on January 15,1856, the state would go bankrupt.

69

Negotiations with the Great Powers offered the only way to avoid catastrophe.

All this is not to say that the allies found the Crimean War easy; for them, too, the campaigning involved strain and unpleasant shocks. The least badly affected, interestingly enough, was France, which for once benefited from being a hybrid power—it was less backward industrially and economically than Russia, and less “unmilitarized” than Britain. The armed forces sent eastward under General Saint-Arnaud were well equipped, well trained because of their North African operations, and reasonably experienced in overseas campaigning; their logistical and medical-support systems were as efficient as any which a midcentury administration could produce; and the French officers showed justified bemusement at their amateur British opposite numbers with their overloaded baggage. The French expeditionary force was by far the largest and made most of the major breakthroughs in the war. To some degree, then, the nation recovered its Napoleonic heritage in this fighting.

By the later stages of the campaign, however, France was beginning to reveal signs of strain. Although it was a rich country, its government had to compete for ready funds with railway constructors and others seeking money from the Crédit Mobilier and other bankers. Gold was being drained away to the Crimea and Constantinople, sending up prices at home; and poor grain harvests didn’t help. Although the full war losses (100,000) were not known, early French enthusiasm for the conflict quickly evaporated. Popular riots over inflation reinforced the argument, widespread after the news of Sevastopol’s fall, that the war was being prolonged only for selfish and ambitious British purposes.

70

By that time, too, Napoleon III was eager to bring the fighting to an end: Russia had been chastised, France’s prestige had been boosted (and would rise further following a great international peace conference in Paris), and it was important not to get too distracted from German and Italian matters by escalating the conflict around the Black Sea. Even if he could not substantially redraw the map of Europe in 1856, Napoleon could certainly feel that France’s prospects were rosier than at any time since Waterloo. For another decade, the post-Crimean War fissures in the old Concert of Europe would allow that illusion to continue.

The British, by contrast, were far from satisfied with the Crimean War. Despite certain efforts at reform, the army was still in the Wellingtonian mold, and its commander, Raglan, had actually been Wellington’s military secretary in the Peninsular War. The cavalry was adequate—as cavalry forces go—but often misused (not just at Balaclava), and could scarcely be deployed in the Sevastopol siegeworks. While the soldiers were toughened old sweats who fought hard, the appalling lack of warm shelter in Crimean rains and winter, the incapacity of the army’s primitive medical services to handle large-scale outbreaks of dysentery and cholera, and the paucity of land transport

caused needless losses and setbacks which infuriated the British nation. More embarrassing still, since the British army, like the Russian, was a long-service force chiefly useful for garrison duties, there was no trained reserve which could be drawn upon in wartime; but while the Russians could at least forcibly conscript hundreds of thousands of raw recruits, laissez-faire Britain could not, leaving the government in the embarrassing position of advertising for foreign mercenaries with which to fill the shortfall of troops in the Crimea. Yet while its army always remained a junior partner to the French, Britain’s navy had no real chance to secure a Nelsonic victory against a foe who prudently withdrew his fleet into fortified harbors.

71

The explosion of public discontent in Britain at the London

Times’

notorious revelations of military incompetence and of the sufferings of the sick and wounded troops can only be mentioned in passing here; it not only led to a change of ministry, but also provoked an earnest debate upon the difficulties inherent in being “a liberal state at war.”

72

More than that, the whole affair revealed that what had seemed to be Britain’s peculiar strengths—a low degree of government, a small imperial army, a heavy reliance upon sea power, an emphasis upon individual freedoms and an unfettered press, the powers of Parliament and of individual ministers—quite easily turned into weaknesses when the country was called upon to carry out an extensive military operation throughout all seasons against a major foe.

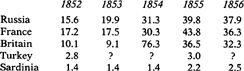

The British response to this test was (rather like the American response to wars in the twentieth century) to allocate vast amounts of money to the armed forces in order to make up for past neglect; and, once again, the crude figures of the military expenditures of the combatants go a long way toward explaining the eventual outcome of the conflict (see

Table 11

).

Table 11. Military Expenditures of the Powers in the Crimean War

73

(millions of pounds)

But even when Britain bestirred itself, it could not swiftly create the proper instruments of power: military spending might multiply, hundreds of steam-driven vessels might be ordered, the expeditionary force might enjoy a

surplus

of tents and blankets and ammunition by 1855, and a belligerent Palmerston might assert the need to break up the Russian Empire; yet Britain’s small army could do little if France

moved toward peace and Austria stayed neutral—which was precisely what happened in the months after the fall of Sevastopol. Only if the British nation and political economy became much more “militarized” could it sustain the war alone against Russia in any meaningful way; but the likely costs were far too high to a political leadership already made uneasy at the strategical, constitutional, and economic difficulties which the Crimean campaign had thrown up.

74

While feeling cheated of a proper victory, therefore, the British also were willing to compromise. What all this did was to make many Europeans (Frenchmen and Austrians as well as Russians) suspicious of London’s aims and reliability, just as it made the British public ever more disgusted at being entangled in continental affairs. While Napoleon’s France moved to the center of the European stage of 1856, therefore, Britain steadily moved to the edge—a drift which the Indian Mutiny (1857) and domestic reform movements could only intensify.

If the Crimean War had shocked the British, that was nothing compared to the blow which had been delivered to Russia’s power and self-esteem—not to mention the losses caused by the 480,000 deaths. “We cannot deceive ourselves any longer,” Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich flatly stated. “… we are both weaker and poorer than the first-class powers, and furthermore poorer not only in material but also in mental resources, especially in matters of administration.”

75

This knowledge drove the reformers in the Russian state toward a whole series of radical changes, most notably the abolition of serfdom. In addition, railway-building and industrialization were given far greater encouragement under Alexander II than under his father. Coal production, iron and steel production, large-scale utilities, and far bigger industrial enterprises were more in evidence from the 1860s onward, and the statistics provided in the economic histories of Russia are impressive enough at first sight.

76

As ever, however, a change of perspective affects one’s judgment. Could this modernization keep pace with, let alone draw ahead of, the vast annual increases in the numbers of poor, uneducated peasants? Could it match the explosive increases in iron and steel production, and manufactures, taking place in the West Midlands, the Ruhr, Silesia, and Pittsburgh during the following two decades? Could it, even with its reorganized army, keep pace with the “military revolution” which the Prussians were about to reveal to the world, and which would emphasize again the

qualitative

over the

quantitative

elements of national strength? The answers to all those questions would disappoint a Russian nationalist, all too aware that his country’s place in Europe was substantially reduced from the position of eminence it had occupied in 1815 and 1848.

As mentioned previously, observers of global politics from de Tocqueville onward felt that the rise of the Russian Empire went in parallel with that of the United States. To be sure, everyone admitted that there were fundamental differences in the political culture and constitutions of those two states, but in World Power terms they seemed very much alike in respect to their geographical size, their “open” and ever-moving frontiers, their fast-growing populations, and their scarcely tapped resources.

77

While much of that is true, the fact remains that throughout the nineteenth century there were important economic discrepancies between the United States and Russia which would have an increasing impact upon their national power. The first of these was in terms of total population, although the gap significantly narrowed between 1816 (Russia 51.2 million, United States 8.5 million) and 1860 (Russia 76 million, United States 31.4 million). What was more pertinent was the character of that population: whereas Russia consisted overwhelmingly of serfs, with low income and low production, Americans on their homesteads or in the swiftly growing cities generally

*

enjoyed a high standard of living, and of national output, relative to other countries. Already in 1800, wages had been about one-third higher than those in western Europe, and that superiority was to be preserved, if not increased, throughout the century. Despite the vast inflow of European immigrants by the 1850s, the ready availability of land in the west, together with constant industrial growth, caused labor to be relatively scarce and wages to be high, which in turn induced manufacturers to invest in labor-saving machinery, further stimulating national productivity. The young republic’s isolation from European power struggles, and the

cordon sanitaire

which the Royal Navy (rather than the Monroe Doctrine) imposed to separate the Old World from the New, meant that the only threat to the United States’ future prosperity could come from Britain itself. Yet despite sore memories of 1776 and 1812, and border disputes in the northwest,

78

an Anglo-American war was unlikely; the flow of British capital and manufactures toward the United States and the return flow of American raw materials (especially cotton) tied the two economies ever closer together and further stimulated American economic growth. Instead of having to divert financial resources into large-scale defense expenditures, therefore, a strategically secure United States could concentrate its own (and British) funds upon developing its vast economic potential. Neither conflict with the Indians nor the 1846 war with Mexico was a substantial drain upon such productive investment.