The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (40 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

Within another three decades—a short time indeed in the course of the Great Power system—that same continent of Europe would be tearing itself apart and several of its members would be close to collapse. Three decades further, and the end would be complete; much of the continent would be economically devastated, parts of it would be in ruins, and its very future would be in the hands of decision-makers in Washington and Moscow.

While it is obvious that no one in 1885 could accurately forecast the ruin and desolation which prevailed in Europe sixty years later, it

was

the case that many acute observers in the late nineteenth century sensed the direction in which the dynamics of world power were driving. Intellectuals and journalists in particular, but also day-to-day politicians, talked and wrote in terms of a vulgar Darwinistic world of struggle, of success and failure, of growth and decline. What was more, the future world order was already seen to have a certain shape, at least by 1895 or 1900.

5

The most noticeable feature of these prognostications was the revival of de Tocqueville’s idea that the United States and Russia would be the two great World Powers of the future. Not surprisingly, this view had lost ground at the time of Russia’s Crimean disaster and its mediocre showing in the 1877 war against Turkey, and during the American Civil War and then in the introspective decades of reconstruction and westward expansion. By the late nineteenth century, however, the industrial and agricultural expansion of the United States and the military expansion of Russia in Asia were causing various European observers to worry about a twentieth-century world order which would, as the saying went, be dominated by the Russian knout and American moneybags.

6

Perhaps because neomercantilist commercial ideas were again prevailing over those of a peaceful, Cobdenite, free-trading global system, there was a much greater tendency than earlier to argue that changing economic power would lead to political and territorial changes as well. Even the usually cautious British prime minister Lord Salisbury admitted in 1898 that the world was divided into the “living” and “dying” powers.

7

The recent Chinese defeat in their 1894–1895 war with Japan, the humiliation of Spain by the United States in their brief 1898 conflict, and the French retreat before Britain over the Fashoda incident on the Upper Nile (1898–1899) were all interpreted as evidence that the “survival of the fittest” dictated the fates of nations as well as animal species. The Great Power struggles were no longer merely over European issues—as they had been in 1830 or even 1860—but over markets and territories that ranged across the globe.

But if the United States and Russia seemed destined by size and population to be among the future Great Powers, who would accompany

them? The “theory of the Three World Empires”—that is, the popular belief that only the three (or, in some accounts, four) largest and most powerful nation-states would remain independent—exercised many an imperial statesman.

8

“It seems to me,” the British minister for the colonies, Joseph Chamberlain, informed an 1897 audience, “that the tendency of the time is to throw all power into the hands of the greater empires, and the minor kingdoms—those which are nonprogressive—seem to fall into a secondary and subordinate place.… ”

9

It was vital for Germany, Admiral Tirpitz urged Kaiser Wilhelm, to build a big navy, so that it would be one of the “four World Powers: Russia, England, America and Germany.”

10

France, too, must be up there, warned a Monsieur Darcy, for “those who do not advance, go backwards and who goes back goes under.”

11

For the long-established powers, Britain, France, and Austria-Hungary, the issue was whether they could maintain themselves in the face of these new challenges to the international status quo. For the new powers, Germany, Italy, and Japan, the problem was whether they could break through to what Berlin termed a “world-political freedom” before it was too late.

It need hardly be said that not every member of the human race was obsessed with such ideas as the nineteenth century came to a close. Many were much more concerned about domestic, social issues. Many clung to the liberal, laissez-faire ideals of peaceful cooperation.

12

Nonetheless there existed in governing elites, military circles, and imperialist organizations a prevailing view of the world order which stressed struggle, change, competition, the use of force, and the organization of national resources to enhance state power. The less-developed regions of the globe were being swiftly carved up, but that was only the beginning of the story; with few more territories to annex, the geopolitician Sir Halford Mackinder argued, efficiency and internal development would have to replace expansionism as the main aim of modern states. There would be a far closer correlation than hitherto “between the larger geographical and the larger historical generalizations,”

13

that is, size and numbers would be more accurately reflected in the international balances, provided that those resources were properly exploited. A country with hundreds of millions of peasants would count for little. On the other hand, even a modern state would be eclipsed also if it did not rest upon a large enough industrial, productive foundation. “The successful powers will be those who have the greatest industrial base,” warned the British imperialist Leo Amery. “Those people who have the industrial power and the power of invention and science will be able to defeat all others.”

14

* * *

Much of the history of international affairs during the following half-century turned out to be a fulfillment of such forecasts. Dramatic changes occurred in the power balances, both inside Europe and without. Old empires collapsed, and new ones arose. The

multipolar

world of 1885 was replaced by a

bipolar

world as early as 1943. The international struggle intensified, and broke into wars totally different from the limited clashes of nineteenth-century Europe. Industrial productivity, with science and technology, became an ever more vital component of national strength. Alterations in the international shares of manufacturing production were reflected in the changing international shares of military power and diplomatic influence. Individuals still counted—who, in the century of Lenin, Hitler, and Stalin, could say they did not?—but they counted in power politics only because they were able to control and reorganize the productive forces of a great state. And, as Nazi Germany’s own fate revealed, the test of world power by war was ruthlessly uncaring to any nation which lacked the industrial-technical strength, and thus the military weaponry, to achieve its leader’s ambitions.

If the broad outlines of these six decades of Great Power struggles were already being suggested in the 1890s, the success or failure of

individual

countries was still to be determined. Obviously, much depended upon whether a country could keep up or increase its manufacturing output. But much also depended, as always, upon the immutable facts of geography. Was a country near the center of international crises, or at the periphery? Was it safe from invasion? Did it have to face two or three ways simultaneously? National cohesion, patriotism, and the controls exercised by the state over its inhabitants were also important; whether a society withstood the strains of war would very much depend upon its internal makeup. It might also depend upon alliance politics and decisionmaking. Was one fighting as part of a large alliance bloc, or in isolation? Did one enter the war at the beginning, or halfway through? Did other powers, formerly neutral, enter the war on the opposite side?

Such questions suggest that any proper analysis of “the coming of a bipolar world, and the crisis of the ‘middle powers’ ” needs to consider three separate but interacting levels of causality: first, the changes in the military-industrial productive base, as certain states became materially more (or less) powerful; second, the geopolitical, strategical, and sociocultural factors which influenced the responses of each

individual

state to these broader shifts in the world balances; and third, the diplomatic and political changes which also affected chances

of success or failure in the great coalition wars of the early twentieth century.

Those

fin de siècle

observers of world affairs agreed that the pace of economic and political change was quickening, and thus likely to make the international order more precarious than before. Alterations had always occurred in the power balances to produce instability and often war. “What made war inevitable,” Thucydides wrote in

The Peleponnesian War

, “was the growth of Athenian power and the fear which this caused in Sparta.”

15

But by the final quarter of the nineteenth century, the changes affecting the Great Power system were more widespread, and usually swifter, than ever before. The global trading and communications network—telegraphs, steamships, railways, modern printing presses—meant that breakthroughs in science and technology, or new advances in manufacturing production, could be transmitted and transferred from one

continent

to another within a matter of years. Within five years of Gilcrist and Thomas’s 1879 invention of a way to turn cheap phosphoric ores into basic steel, there were eighty-four basic converters in operation in western and central Europe,

16

and the process had also crossed the Atlantic. The result was

more

than a shift in the respective national shares of steel output; it also implied a significant shift in military potential.

Military potential is, as we have seen, not the same as military power. An economic giant could prefer, for reasons of its political culture or geographical security, to be a military pigmy, while a state without great economic resources could nonetheless so organize its society as to be a formidable military power. Exceptions to the simplistic equation “economic strength = military strength” exist in this period, as in others, and will need to be discussed below. Yet in an era of modern, industrialized warfare, the link between economics and strategy was becoming tighter. To understand the long-term shifts affecting the international power balances between the 1880s and the Second World War, it is necessary to look at the economic data. These data have been selected with a view to assessing a nation’s potential for war, and therefore do not include some well-known economic indices

*

which are less helpful in that respect.

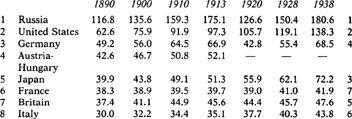

Population size by itself is never a reliable indicator of power, but

Table 12

does suggest how, at least demographically, Russia and the United States could be viewed as a different sort of Great Power from

the others, with Germany and (later) Japan beginning to draw a little away from the remainder.

Table 12. Total Population of the Powers, 1890–1938

17

(millions)

There are, however, two ways of “controlling” the raw data of

Table 12

. The first is to compare the total population of a country with the part of it that is living in urban areas (

Table 13

), for that is usually a significant indicator of industrial/commercial modernization; the second is to correlate those findings with the per capita levels of industrialization, as measured against the “benchmark” country of Great Britain (

Table 14

). Both exercises are enormously instructive, and tend to reinforce each other.

Without getting into too detailed an analysis of the figures in

Tables 13

and

14

at this stage, several broad generalizations can be made. Once such measures of “modernization” as the size of urban population and the extent of industrialization are introduced, the positions of most of the powers are significantly altered from those in

Table 12

: Russia drops from first to last, at least until its 1930s industrial expansion, Britain and Germany gain in position, and the United States’ unique combination of having both a populous

and

a highly industrialized society stands out. Even at the beginning of this period, the gap between the strongest and the weakest of the Great Powers is large, both absolutely and relatively; by the eve of the Second World War, there still remain enormous differences. The process of modernization might involve all these countries going through the same “phases”;

18

it did not mean that, in

power

terms, each would benefit to the same degree.

The important

differences

between the Great Powers emerge yet more clearly when one examines detailed data about industrial productivity. Since iron and steel output has often been taken as an indicator of potential military strength in this period, as well as of industrialization

per se

, the relevant figures are reproduced in

Table 15

.