The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (35 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

Nevertheless, the fact remains that France’s

relative

power was being eroded in economic terms as well as in other respects. While France was, to repeat, greater than Prussia or the Habsburg Empire, there was no sphere in which it was the decisive leader, as it had been a century earlier. Its army was large, but second in numbers to Russia’s. Its fleet, erratically supported by successive French administrations, was usually second in size to the Royal Navy—but the gap

between them was enormous. In terms of manufacturing output and national product, France was falling behind its trail-blazing neighbor. Its launching of

La Gloire

was swiftly eclipsed by the Royal Navy’s H.M.S.

Warrior

, just as its field artillery fell behind Krupp’s newer designs. It did play a role outside Europe, but again its possessions and influence were far less extensive than Britain’s.

All this points to another acute problem which made difficult the measurement—and often the deployment—of France’s undoubted strength. It remained a classic

hybrid

power,

57

frequently torn between its European and its non-European interests; and this in turn affected its diplomacy, which was already complicated enough by ideological and balance-of-power considerations. Was it more important to check Russia’s advance upon Constantinople than to block British pretensions in the Levant? Should it be trying to prize Austria out of Italy, or to challenge the Royal Navy in the English Channel? Should it encourage or oppose the early moves toward German unification? Given the pros and cons attached to each of these policies, it is not surprising that the French were often found ambivalent and hesitating, even when they were regarded as a full member of the Concert.

On the other hand, it must not be forgotten that the general circumstances which constrained France also enabled it to act as a check upon the other Great Powers. If this was especially the case under Napoleon III, it was also true, incipiently, even in the late 1820s. Simply because of its size, France’s recovery had implications in the Iberian and Italian peninsulas, in the Low Countries, and farther afield. Both the British and the Russian attempts to influence events in the Ottoman Empire needed to take France into account. It was France, much more than the wavering Habsburg Empire or even Britain, which posed the chief military check to Russia during the Crimean War. It was France which undermined the Austrian position in Italy, and it was chiefly France which, less dramatically, ensured that the British Empire did not have a complete monopoly of influence along the African and Chinese coasts. Finally, when the Austro-Prussian “struggle for mastery in Germany” rose to a peak, both rivals revealed their deep concern over what Napoleon III might or might not do. In sum, following its recovery after 1815 France during the decades following remained a considerable power, very active diplomatically, reasonably strong militarily, and better to have as a friend than as a rival—even if its own leaders were aware that it was no longer so dominant as in the previous two centuries.

Russia’s

relative

power was to decline the most during the post-1815 decades of international peace and industrialization—although that was not fully evident until the Crimean War (1854–1856) itself. In 1814 Europe had been awed as the Russian army advanced to the west, and the Paris crowds had prudently shouted “Vive l’empereur Alexandre!” as the czar entered their city behind his brigades of cossacks. The peace settlement itself, with its archconservative emphasis against future territorial and political change, was underwritten by a Russian army of 800,000 men—as far superior to any rivals on land as the Royal Navy was to other fleets at sea. Both Austria and Prussia were overshadowed by this eastern colossus, fearing its strength even as they proclaimed monarchical solidarity with it. If anything, Russia’s role as the gendarme of Europe increased when the messianic Alexander I was succeeded by the autocratic Nicholas I (1825–1855); and the latter’s position was further enhanced by the revolutionary events of 1848–1849, when, as Palmerston noted, Russia and Britain were the only powers that were “standing upright.”

58

The desperate appeals of the Habsburg government for aid in suppressing the Hungarian revolt were rewarded by the dispatch of three Russian armies. By contrast, the waverings of Frederick William IV of Prussia toward internal reform movements, together with the proposals for changes in the German Federation, provoked unrelenting Russian pressure until the court at Berlin accepted policies of domestic reaction and the diplomatic retreat at Oelmuetz. As for the “forces of change” themselves after 1848, all elements, whether defeated Polish and Hungarian nationalists, or frustrated bourgeois liberals, or Marxists, were agreed that the chief bulwark against progress in Europe would long remain the empire of the czars.

Yet at the economic and technological level, Russia was losing ground in an alarming way between 1815 and 1880, at least relative to other powers. This is not to say that there was no economic improvement, even under Nicholas I, many of whose officials had been hostile to market forces or to any signs of modernization. The population grew rapidly (from 51 million in 1816, to 76 million in 1860, to 100 million in 1880), and that of the towns grew the fastest of all. Iron production increased, and the textile industry multiplied in size. Between 1804 and 1860, it was claimed, the number of factories or industrial enterprises rose from 2,400 to over 15,000. Steam engines and modern machinery were imported from the west; and from the 1830s onward a railway network began to emerge. The very fact that historians have quarreled over whether an “industrial revolution” occurred

in Russia during these decades confirms that things were on the move.

59

But the blunt point was that the rest of Europe was moving far faster and that Russia was losing ground. Because of its far bigger population, it had easily possessed the largest

total

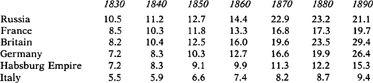

GNP in the early nineteenth century. Two generations later, that was no longer the case, as shown in

Table 9

.

Table 9. GNP of the European Great Powers, 1830–1890

60

(at market prices, in 1960 U.S. dollars and prices; in billions)

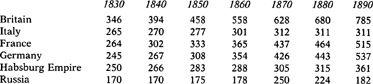

But these figures were even more alarming when the per capita amount of GNP is studied (see

Table 10

).

Table 10. Per Capita GNP of the European Great Powers, 1830–1890

61

(in 1960 U.S. dollars and prices)

The figures show that the increase in Russia’s

total

GNP which occurred during these years was overwhelmingly due to the rise in its population, whether by births or by conquests in Turkestan and elsewhere, and had little to do with real increases in productivity (especially industrial productivity). Russia’s per capita income, and national product, had always been behind that of western Europe; but it now fell even further behind, from (for example) one-half of Britain’s per capita income in 1830 to one-quarter of that figure sixty years later.

In the same way, the doubling of Russia’s iron production in the early nineteenth century compared badly with Britain’s

thirtyfold

increase;

62

within two generations, Russia had changed from being Europe’s largest producer and exporter of iron into a country increasingly dependent upon imports of western manufactures. Even the improvements in rail and steamship communications need to be put in

perspective. By 1850 Russia had little over 500 miles of railroad, compared with the United States’ 8,500 miles; and much of the increase in steamship trade, on the great rivers or out of the Baltic and Black seas, revolved around the carriage of grains needed for the burgeoning home population and to pay for imported manufactured goods by the dispatch of wheat to Britain. What new developments occurred were all too frequently in the hands of foreign merchants and entrepreneurs (the export trade certainly was), and turned Russia ever more into a supplier of

primary

materials for advanced economies. On closer examination of the evidence, it appears that most of the new “factories” and “industrial enterprises” employed fewer than sixteen people, and were scarcely mechanized at all. A general lack of capital, low consumer demand, a minuscule middle class, vast distances and extreme climates, and the heavy hand of an autocratic, suspicious state made the prospects for industrial “takeoff” in Russia more difficult than in virtually anywhere else in Europe.

63

For a long while, these ominous economic trends did not translate into a noticeable Russian military weakness. On the contrary, the post-1815 preference shown by the Great Powers for

ancien régime

structures in general could nowhere be more clearly seen than in the social composition, weaponry, and tactics of their armies. Still in the shadows cast by the French Revolution, governments were more concerned about the political and social reliability of their armed forces than about military reforms; and the generals themselves, no longer facing the test of a great war, emphasized hierarchy, obedience, and caution—traits reinforced by Nicholas I’s obsession with formal parades and grand marches. Given these general circumstances, the sheer size of the Russian army and the steadiness of its mass conscripts appeared more impressive to outside observers than such arcane matters as military logistics or the general level of education among the officer corps. What was more, the Russian army

was

active and often successful in its frequent campaigns of expansion into the Caucasus and across Turkestan—thrusts which were already beginning to worry the British in India, and to make Anglo-Russian relations in the nineteenth century much more strained than they had been in the eighteenth.

64

Equally impressive to outside eyes was the Russian suppression of the Hungarian rebellion of 1848–1849, and the czar’s claim that he stood ready to dispatch 400,000 troops to quell the contemporaneous revolt in Paris. What those observers failed to note was the less imposing fact that the greater part of the Russian army was always pinned down by internal garrison duties, by “police” actions in Poland and the Ukraine, and by other activities, such as border patrols and the Military Colonies; and that what was left was not particularly efficient—of the 11,000 casualties incurred in the Hungarian campaign, for example,

all but 1,000 were caused by diseases, because of the inefficiency of the army’s logistical and medical services.

65

The campaigning in the Crimea from 1854 until 1855 provided an all too shocking confirmation of Russia’s backwardness. Czarist forces could not be concentrated. Allied operations in the Baltic (while never very serious), together with the threat of Swedish intervention, pinned down as many as 200,000 Russian troops in the north. The early campaigning in the Danubian principalities, and the far greater danger that Austria would turn its threats of intervention into reality, posed a danger to Bessarabia, the western Ukraine, and Russian Poland. The fighting against the Turks in the Caucasus placed immense demands upon both troops and supply systems, as did the defense of Russian territories in the Far East.

66

When the Anglo-French assault on the Crimea brought the war to a highly sensitive region of Russian territory, the armed forces of the czar were incapable of repudiating such an invasion.

At sea, Russia possessed a fair-sized navy, with competent admirals, and it was able to destroy completely the weaker Turkish fleet at Sinope in November 1853; but as soon as the Anglo-French fleets entered the fray, the positions were reversed.

67

Many Russian vessels were fir-built and unseaworthy, their firepower was inadequate, and their crews were half-trained. The allies had many more steam-driven warships, some of them armed with shrapnel shells and Congreve rockets. Above all, Russia’s enemies had the industrial capacity to build newer vessels (including dozens of steam-driven gunboats), so that their advantage became greater as the war lengthened.