The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (31 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

There are today on the plains of India and China men and women, plague-ridden and hungry, living lives little better, to outward appearance, than those of the cattle that toil with them by day and share their places of sleep by night. Such Asiatic standards, and such unmechanised horrors, are the lot of those who increase their numbers without passing through an industrial revolution.

9

Before discussing the effects of the Industrial Revolution upon the Great Power system, it will be as well to understand its impacts farther afield, especially upon China, India, and other non-European societies. The losses they suffered were twofold, both relative and absolute. It was not the case, as was once fancied, that the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America lived a happy, ideal existence prior to the impact of western man. “The elemental truth must be stressed that the characteristic

of any country before its industrial revolution and modernization is poverty.… with low productivity, low output per head, in traditional agriculture, any economy which has agriculture as the main constituent of its national income does not produce much of a surplus above the immediate requirements of consumption.… ”

10

On the other hand, in view of the fact that in 1800 agricultural production formed the basis of both European and non-European societies, and of the further fact that in countries such as India and China there also existed many traders, textile producers, and craftsmen, the differences in per capita income were not enormous; an Indian handloom weaver, for example, may have earned perhaps as much as half of his European equivalent prior to industrialization. What this also meant was that, given the sheer numbers of Asiatic peasants and craftsmen, Asia still contained a far larger share of world manufacturing output

*

than did the much less populous Europe before the steam engine and the power loom transformed the world’s balances.

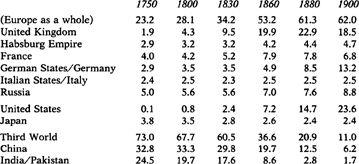

Just how dramatically those balances shifted in consequence of European industrialization and expansion can be seen in Bairoch’s two ingenious calculations (see

Tables 6

–

7

).

11

The root cause of these transformations, it is clear, lay in the staggering increases in productivity emanating from the Industrial Revolution. Between, say, the 1750s and the 1830s the mechanization of spinning in Britain had increased productivity in that sector alone by a factor of 300 to 400, so it is not surprising that the British share of total world manufacturing rose dramatically—and continued to rise as it turned itself into the “first industrial nation.”

12

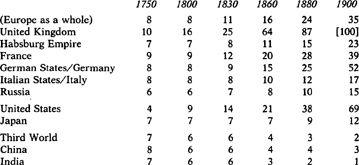

When other European states and the United States followed the path to industrialization, their shares also rose steadily, as did their per capita levels of industrialization and their national wealth. But the story for China and India was quite a different one. Not only did their shares of total world manufacturing shrink relatively, simply because the West’s output was rising so swiftly; but in some cases their economies declined absolutely, that is, they de-industrialized, because of the penetration of their traditional markets by the far cheaper and better products of the Lancashire textile factories. After 1813 (when the East India Company’s trade monopoly ended), imports of cotton fabrics into India rose spectacularly, from 1 million yards (1814) to 51 million (1830) to 995 million (1870), driving out many of the traditional domestic producers in the process. Finally—and this returns us to Ashton’s point about the grinding poverty of “those who increase their numbers without passing through an industrial revolution”—the large rise in the populations of China, India, and other Third World countries probably reduced their general per capita income from one generation to the next. Hence Bairoch’s remarkable—and horrifying—suggestion that whereas the per capita levels of industrialization in Europe and the Third World may have been not too far apart from each other in 1750, the latter’s was only one-eighteenth of the former’s (2 percent to 35 percent) by 1900, and only one-fiftieth of the United Kingdom’s (2 percent to 100 percent).

Table 6. Relative Shares of World Manufacturing Output, 1750-1900

Table 7. Per Capita Levels of Industrialization, 1750–1900

(relative to U.K. in 1900 = 100)

The “impact of western man” was, in all sorts of ways, one of the most noticeable aspects of the dynamics of world power in the nineteenth century. It manifested itself not only in a variety of economic relationships—ranging from the “informal influence” of coastal traders, shippers, and consuls to the more direct controls of planters, railway builders, and mining companies

13

—but also in the penetrations of explorers, adventurers, and missionaries, in the introduction of western diseases, and in the proselytization of western faiths. It occurred as much in the centers of continents—westward from the Missouri,

southward from the Aral Sea—as it did up the mouths of African rivers and around the coasts of Pacific archipelagoes. If it eventually had its impressive monuments in the roads, railway networks, telegraphs, harbors, and civic buildings which (for example) the British created in India, its more horrific side was the bloodshed, rapine, and plunder which attended so many of the colonial wars of the period.

14

To be sure, the same traits of force and conquest had existed since the days of Cortez, but now the pace was accelerating. In the year 1800, Europeans occupied or controlled 35 percent of the land surface of the world; by 1878 this figure had risen to 67 percent, and by 1914 to over 84 percent.

15

The advanced technology of steam engines and machine-made tools gave Europe decisive economic and military advantages. The improvements in the muzzle-loading gun (percussion caps, rifling, etc.) were ominous enough; the coming of the breechloader, vastly increasing the rate of fire, was an even greater advance; and the Gatling guns, Maxims, and light field artillery put the final touches to a new “firepower revolution” which quite eradicated the chances of a successful resistance by indigenous peoples reliant upon older weaponry. Furthermore, the steam-driven gunboat meant that European sea power, already supreme in open waters, could be extended inland, via major waterways like the Niger, the Indus, and the Yangtze: thus the mobility and firepower of the ironclad

Nemesis

during the Opium War actions of 1841 and 1842 was a disaster for the defending Chinese forces, which were easily brushed aside.

16

It was true, of course, that physically difficult terrain (e.g., Afghanistan) blunted the drives of western military imperialism, and that among non-European forces which adopted the newer weapons and tactics—like the Sikhs and the Algerians in the 1840s—the resistance was far greater. But whenever the struggle took place in open country where the West could deploy its machine guns and heavier weapons, the issue was never in doubt. Perhaps the greatest disparity of all was seen at the very end of the century, during the battle of Omdurman (1898), when in one half-morning the Maxims and Lee-Enfield rifles of Kitchener’s army destroyed 11,000 Dervishes for the loss of only forty-eight of their own troops. In consequence, the firepower gap, like that which had opened up in industrial productivity, meant that the leading nations possessed resources fifty or a hundred times greater than those at the bottom. The global dominance of the West, implicit since da Gama’s day, now knew few limits.

If the Punjabis and Annamese and Sioux and Bantu were the “losers” (to use Eric Hobsbawm’s term)

17

in this early-nineteenth-century expansion, the British were undoubtedly the “winners.” As noted in the

previous chapter

, they had already achieved a remarkable degree of global preeminence by 1815, thanks to their adroit combination of naval mastery, financial credit, commercial expertise, and alliance diplomacy. What the Industrial Revolution did was to enhance the position of a country already made supremely successful in the preindustrial, mercantilist struggles of the eighteenth century, and then to transform it into a different sort of power. If (to repeat) the pace of change was gradual rather than revolutionary, the results were nonetheless highly impressive. Between 1760 and 1830, the United Kingdom was responsible for around “two-thirds of Europe’s industrial growth of output,”

18

and its share of world manufacturing production leaped from 1.9 to 9.5 percent; in the next thirty years, British industrial expansion pushed that figure to 19.9 percent, despite the spread of the new technology to other countries in the West. Around 1860, which was probably when the country reached its zenith in relative terms, the United Kingdom produced 53 percent of the world’s iron and 50 percent of its coal and lignite, and consumed just under half of the raw cotton output of the globe. “With 2 percent of the world’s population and 10 percent of Europe’s, the United Kingdom would seem to have had a capacity in modern industries equal to 40–45 percent of the world’s potential and 55–60 percent of that in Europe.”

19

Its energy consumption from modern sources (coal, lignite, oil) in 1860 was five times that of either the United States or Prussia/Germany, six times that of France, and 155 times that of Russia! It alone was responsible for one-fifth of the world’s commerce, but for two-fifths of the trade in manufactured goods. Over one-third of the world’s merchant marine flew under the British flag, and that share was steadily increasing. It was no surprise that the mid-Victorians exulted at their unique state, being now (as the economist Jevons put it in 1865) the trading center of the universe:

The plains of North America and Russia are our corn fields; Chicago and Odessa our granaries; Canada and the Baltic are our timber forests; Australasia contains our sheep farms, and in Argentina and on the western prairies of North America are our herds of oxen; Peru sends her silver, and the gold of South Africa and Australia flows to London; the Hindus and the Chinese grow tea for us, and our coffee, sugar and spice plantations are in all the Indies. Spain and France are our vineyards and the Mediterranean our fruit garden; and our cotton grounds, which for long have occupied the

Southern United States, are now being extended everywhere in the warm regions of the earth.

20

Since such manifestations of self-confidence, and the industrial and commercial statistics upon which they rested, seemed to suggest a position of unequaled dominance on Britain’s part, it is fair to make several other points which put this all in a better context. First—although it is a somewhat pedantic matter—it is unlikely that the country’s gross national product (GNP) was ever the largest in the world during the decades following 1815. Given the sheer size of China’s population (and, later, Russia’s) and the obvious fact that agricultural production and distribution formed the basis of national wealth everywhere, even in Britain prior to 1850, the latter’s overall GNP never looked as impressive as its per capita product or its stage of industrialization. Still, “by itself the volume of total GNP has no important significance”;

21

the physical product of hundreds of millions of peasants may dwarf that of five million factory workers, but since most of it is immediately consumed, it is far less likely to lead to surplus wealth or decisive military striking power. Where Britain was strong, indeed unchallenged, in 1850 was in modern, wealth-producing industry, with all the benefits which flowed from it.

On the other hand—and this second point is not a pedantic one—Britain’s growing industrial muscle was not organized in the post-1815 decades to give the state swift access to military hardware and manpower as, say, Wallenstein’s domains did in the 1630s or the Nazi economy was to do. On the contrary, the ideology of laissez-faire political economy, which flourished alongside this early industrialization, preached the causes of eternal peace, low government expenditures (especially on defense), and the reduction of state controls over the economy and the individual. It might be necessary, Adam Smith had conceded in

The Wealth of Nations

(1776), to tolerate the upkeep of an army and a navy in order to protect British society “from the violence and invasion of other independent societies”; but since armed forces

per se

were “unproductive” and did not add value to the national wealth in the way that a factory or a farm did, they ought to be reduced to the lowest possible level commensurate with national safety.

22

Assuming (or, at least, hoping) that war was a last resort, and ever less likely to occur in the future, the disciples of Smith and even more of Richard Cobden would have been appalled at the idea of organizing the state for war. As a consequence, the “modernization” which occurred in British industry and communications was not paralleled by improvements in the army, which (with some exceptions)

23

stagnated in the post-1815 decades.