The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (32 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

However preeminent the British economy in the mid-Victorian period, therefore, it was probably less “mobilized” for conflict than at any

time since the early Stuarts. Mercantilist measures, with their emphasis upon the links between national security and national wealth, were steadily eliminated: protective tariffs were abolished; the ban on the export of advanced technology (e.g., textile machinery) was lifted; the Navigation Acts, designed among other things to preserve a large stock of British merchant ships and seamen for the event of war, were repealed; imperial “preferences” were ended. By contrast, defense expenditures were held to an absolute minimum, averaging around £15 million a year in the 1840s and not above £27 million in the more troubled 1860s; yet in the latter period Britain’s GNP totaled about £1 billion. Indeed, for fifty years and more following 1815 the armed services consumed only about 2–3 percent of GNP, and central government expenditures as a whole took much less than 10 percent—proportions which were far less than in either the eighteenth or the twentieth century.

24

These would have been impressively low figures for a country of modest means and ambitions. For a state which managed to “rule the waves,” which possessed an enormous, far-flung empire, and which still claimed a large interest in preserving the European balance of power, they were truly remarkable.

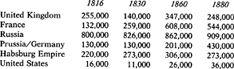

Like that of the United States in, say, the early 1920s, therefore, the size of the British economy in the world was not reflected in the country’s fighting power; nor could its laissez-faire institutional structures, with a minuscule bureaucracy increasingly divorced from trade and industry, have been able to mobilize British resources for an all-out war without a great upheaval. As we shall see below, even the more limited Crimean War shook the system severely, yet the concern which that exposure aroused soon faded away. Not only did the mid-Victorians show ever less enthusiasm for military interventions in Europe, which would always be expensive, and perhaps immoral, but they reasoned that the equilibrium between the continental Great Powers which generally prevailed during the six decades after 1815 made any full-scale commitment on Britain’s part unnecessary. While it did strive, through diplomacy and the movement of naval squadrons, to influence political events along the vital peripheries of Europe (Portugal, Belgium, the Dardanelles), it tended to abstain from intervention elsewhere. By the late 1850s and early 1860s, even the Crimean campaign was widely regarded as a mistake. Because of this lack of inclination and effectiveness, Britain did not play a major role in the fate of Piedmont in the critical year of 1859, it disapproved of Palmerston and Russell’s “meddling” in the Schleswig-Holstein affair of 1864, and it watched from the sidelines when Prussia defeated Austria in 1866 and France four years later. It is not surprising to see that Britain’s military capacity was reflected in the relatively modest size of its army during this period (see

Table 8

), little of which could, in any case, be mobilized for a European theater.

Table 8. Military Personnel of the Powers, 1816-1880

25

Even in the extra-European world, where Britain preferred to deploy its regiments, military and political officials in places such as India were almost always complaining of the

inadequacy

of the forces they commanded, given the sheer magnitude of the territories they controlled. However imposing the empire may have appeared on a world map, district officers knew that it was being run on a shoestring. But all this is merely saying that Britain was a different sort of Great Power by the early to middle nineteenth century, and that its influence could not be measured by the traditional criteria of military hegemony. Where it

was

strong was in certain other realms, each of which was regarded by the British as far more valuable than a large and expensive standing army.

The first of these was in the naval realm. For over a century before 1815, of course, the Royal Navy had usually been the largest in the world. But that maritime mastery had frequently been contested, especially by the Bourbon powers. The salient feature of the eighty years which followed Trafalgar was that no other country, or combination of countries, seriously challenged Britain’s control of the seas. There was, it is true, the occasional French “scare”; and the Admiralty also kept a wary eye upon Russian shipbuilding programs and upon the American construction of large frigates. But each of those perceived challenges faded swiftly, leaving British sea power to exercise (in Professor Lloyd’s words) “a wider influence than has ever been seen in the history of maritime empires.”

26

Despite a steady reduction in its own numbers after 1815, the Royal Navy was at some times probably as powerful as the next three or four navies in actual fighting power. And its major fleets

were

a factor in European politics, at least on the periphery. The squadron anchored in the Tagus to protect the Porguguese monarchy against internal or external dangers; the decisive use of naval force in the Mediterranean (against the Algiers pirates in 1816; smashing the Turkish fleet at Navarino in 1827; checking Mehemet Ali at Acre in 1840); and the calculated dispatch of the fleet to anchor before the Dardanelles whenever the “Eastern Question” became acute: these were manifestations of British sea power which, although geographically restricted, nonetheless weighed in the minds of European governments. Outside Europe, where smaller Royal Navy fleets or even individual warships engaged in a whole host of activities—suppressing

piracy, intercepting slaving ships, landing marines, and overawing local potentates from Canton to Zanzibar—the impact seemed perhaps even more decisive.

27

The second significant realm of British influence lay in its expanding colonial empire. Here again, the overall situation was a far less competitive one than in the preceding two centuries, where Britain had had to fight repeatedly for empire against Spain, France, and other European states. Now, apart from the occasional alarm about French moves in the Pacific or Russian encroachments in Turkestan, no serious rivals remained. It is therefore hardly an exaggeration to suggest that between 1815 and 1880 much of the British Empire existed in a power-political vacuum, which is why its colonial army could be kept relatively low. There were, it is true, limits to British imperialism—and certain problems, with the expanding American republic in the western hemisphere as well as with France and Russia in the eastern. But in many parts of the tropics, and for long periods of time, British interests (traders, planters, explorers, missionaries) encountered no foreigners other than the indigenous peoples.

This relative lack of external pressure, together with the rise of laissez-faire liberalism at home, caused many a commentator to argue that colonial acquisitions were unnecessary, being merely a set of “millstones” around the neck of the overburdened British taxpayer. Yet whatever the rhetoric of anti-imperialism within Britain, the fact was that the empire continued to grow, expanding (according to one calculation) at an average annual pace of about 100,000 square miles between 1815 and 1865.

28

Some were strategical/commercial acquisitions, like Singapore, Aden, the Falkland Islands, Hong Kong, Lagos; others were the consequence of land-hungry white settlers, moving across the South African veldt, the Canadian prairies, and the Australian outback—whose expansion usually provoked a native resistance that often had to be suppressed by troops from Britain or British India. And even when formal annexations were resisted by a home government perturbed at this growing list of new responsibilities, the “informal influence” of an expanding British society was felt from Uruguay to the Levant and from the Congo to the Yangtze. Compared with the sporadic colonizing efforts of the French and the more localized internal colonization by the Americans and the Russians, the British as imperialists were in a class of their own for most of the nineteenth century.

The third area of British distinctiveness and strength lay in the realm of finance. To be sure, this element can scarcely be separated from the country’s general industrial and commercial progress; money had been necessary to fuel the Industrial Revolution, which in turn produced much more money, in the form of returns upon capital invested. And, as the preceding chapter showed, the British government

had long known how to exploit its credit in the banking and stock markets. But developments in the financial realm by the mid-nineteenth century were both qualitatively and quantitatively different from what had gone before. At first sight, it is the quantitative difference which catches the eye. The long peace and the easy availability of capital in the United Kingdom, together with the improvements in the country’s financial institutions, stimulated Britons to invest abroad as never before: the £6 million or so which was annually exported in the decade following Waterloo had risen to over £30 million a year by midcentury, and to a staggering £75 million a year between 1870 and 1875. The resultant income to Britain from such interest and dividends, which had totaled a handy £8 million each year in the late 1830s, was over £50 million a year by the 1870s; but most of that was promptly reinvested overseas, in a sort of virtuous upward spiral which not only made Britain ever wealthier but gave a continual stimulus to global trade and communications.

The consequences of this vast export of capital were several, and important. The first was that the returns on overseas investments significantly reduced the annual trade gap on visible goods which Britain always incurred. In this respect, investment income added to the already considerable invisible earnings which came from shipping, insurance, bankers’ fees, commodity dealing, and so on. Together, they ensured that not only was there never a balance-of-payments crisis, but Britain became steadily richer, at home and abroad. The second point was that the British economy acted as a vast bellows, sucking in enormous amounts of raw materials and foodstuffs and sending out vast quantities of textiles, iron goods, and other manufactures; and this pattern of visible trade was paralleled, and complemented, by the network of shipping lines, insurance arrangements, and banking links which spread outward from London (especially), Liverpool, Glasgow, and most other cities in the course of the nineteenth century.

Given the openness of the British home market and London’s willingness to reinvest overseas income in new railways, ports, utilities, and agricultural enterprises from Georgia to Queensland, there was a general complementarity between visible trade flows and investment patterns.

*

Add to this the growing acceptance of the gold standard and the development of an international exchange and payments mechanism based upon bills drawn on London, and it was scarcely surprising that the mid-Victorians were convinced that by following the principles of classical political economy, they had discovered the secret

which guaranteed both increasing prosperity and world harmony. Although many individuals—Tory protectionists, oriental despots, newfangled socialists—still seemed too purblind to admit this truth, over time everyone would surely recognize the fundamental validity of laissez-faire economics and utilitarian codes of government.

29

While all this made Britons wealthier than ever in the short term, did it not also contain elements of strategic danger in the longer term? With the wisdom of retrospect, one can detect at least two consequences of these structural economic changes which would later affect Britain’s relative power in the world. The first was the way in which the country was contributing to the long-term expansion of other nations, both by establishing and developing foreign industries and agriculture with repeated financial injections and by building railways, harbors, and steamships which would enable overseas producers to rival its own production in future decades. In this connection, it is worth noting that while the coming of steam power, the factory system, railways, and later electricity enabled the British to overcome natural, physical obstacles to higher productivity, and thus increased the nation’s wealth and strength, such inventions helped the United States, Russia, and central Europe even more, because the natural, physical obstacles to the development of their landlocked potential were much greater. Put crudely, what industrialization did was to equalize the chances to exploit one’s own indigenous resources and thus to take away some of the advantages hitherto enjoyed by smaller, peripheral, naval-cum-commercial states and to give them to the great land-based states.

30

The second potential strategical weakness lay in the increasing dependence of the British economy upon international trade and, more important, international finance. By the middle decades of the nineteenth century, exports composed as much as one-fifth of total national income,

31

a far higher proportion than in Walpole’s or Pitt’s time; for the enormous cotton-textile industry in particular, overseas markets were vital. But foreign imports, both of raw materials and (increasingly) of foodstuffs, were also becoming vital as Britain moved from being a predominantly agricultural to being a predominantly urban/industrial society. And in the fastest-growing sector of all, the “invisible” services of banking, insurance, commodity-dealing, and overseas investment, the reliance upon a world market was even more critical. The world was the City of London’s oyster, which was all very well in peacetime; but what would the situation be if ever it came to another Great Power war? Would Britain’s export markets be even more badly affected than in 1809 and 1811–1812? Was not the entire economy, and domestic population, becoming too dependent upon imported goods, which might easily be cut off or suspended in periods of conflict? And would not the London-based global banking and financial system collapse

at the onset of another world war, since the markets might be closed, insurances suspended, international capital transfers retarded, and credit ruined? In such circumstances, ironically, the advanced British economy might be more severely hurt than a state which was less “mature” but also less dependent upon international trade and finance.