The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (105 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

The second, and in many ways less expected, sector of decline is agriculture. Only a decade ago, experts in that subject were predicting a frightening global imbalance between feeding requirements and farming output.

232

But such a scenario of famine and disaster stimulated two powerful responses. The first was a massive investment into American farming from the 1970s onward, fueled by the prospect of ever-larger overseas food sales; the second was the enormous (western-world-funded) investigation into scientific means of increasing Third World crop outputs, which has been so successful as to turn growing

numbers of such countries into food

exporters

, and thus competitors of the United States. These two trends are separate from, but have coincided with, the transformation of the EEC into a major producer of agricultural surpluses, because of its price-support system. In consequence, experts now refer to a “world awash in food,”

233

which in turn leads to sharp declines in agricultural prices and in American food exports—and drives many farmers out of business.

It is not surprising, therefore, that these economic problems have led to a surge in protectionist sentiment throughout many sectors of the American economy, and among businessmen, unions, farmers, and their congressmen. As with the “tariff reform” agitation in Edwardian Britain,

234

the advocates of increased protection complain of unfair foreign practices, of “dumping” below-cost manufactures on the American market, and of enormous subsidies to foreign farmers—which, they maintain, can only be answered by U.S. administrations abandoning their laissez-faire policy on trade and instituting tough counter measures. Many of those individual complaints (e.g., of Japan shipping below-cost silicon chips to the American market) have been valid. More broadly, however, the surge in protectionist sentiment is also a reflection of the erosion of the previously unchallenged U.S. manufacturing supremacy. Like mid-Victorian Britons, Americans after 1945 favored free trade and open competition, not just because they held that global commerce and prosperity would be boosted in the process, but also because they knew that they were most likely to benefit from the abandonment of protectionism. Forty years later, with that confidence ebbing, there is a predictable shift of opinion in favor of protecting the domestic market and the domestic producer. And, just as in that earlier British case, defenders of the existing system point out that enhanced tariffs might not only make domestic products

less

competitive internationally, but that there also could be various external repercussions—a global tariff war, blows against American exports, the undermining of the currencies of certain newly industrializing countries, and a return to the economic crisis of the 1930s.

Along with these difficulties affecting American manufacturing and agriculture there are unprecedented turbulences in the nation’s finances. The uncompetitiveness of U.S. industrial products abroad and the declining sales of agricultural exports have together produced staggering deficits in visible trade—$160 billion in the twelve months to May 1986—but what is more alarming is that such a gap can no longer be covered by American earnings on “invisibles,” which is the traditional recourse of a mature economy (e.g., Great Britain before 1914). On the contrary, the only way the United States can pay its way in the world is by importing ever-larger sums of capital, which has transformed it from being the world’s largest creditor to the world’s largest debtor nation

in the space of a few years

.

Compounding this problem—in the view of many critics,

causing

this problem

235

—have been the budgetary policies of the U.S. government itself. Even in the 1960s, there was a tendency for Washington to rely upon deficit finance, rather than additional taxes, to pay for the increasing cost of defense and social programs. But the decisions taken by the Reagan administration in the early 1980s—i.e., large-scale increases in defense expenditures, plus considerable decreases in taxation, but

without

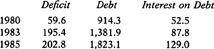

significant reductions in federal spending elsewhere—have produced extraordinary rises in the deficit, and consequently in the national debt, as shown in

Table 49

.

Table 49. U.S. Federal Deficit, Debt, and Interest, 1980–1985

236

(billions of dollars)

The continuation of such trends, alarmed voices have pointed out, would push the U.S. national debt to around $13

trillion

by the year 2000 (fourteen times that of 1980), and the interest payments on such debt to $1.5

trillion

(twenty-nine times that of 1980).

237

In fact, a lowering of interest rates could bring down those estimates,

238

but the overall trend is still very unhealthy. Even if federal deficits could be reduced to a “mere” $100 billion annually, the compounding of national debt and interest payments by the early twenty-first century will still cause quite unprecedented totals of money to be diverted in that direction. Historically, the only other example which comes to mind of a Great Power so increasing its indebtedness in

peacetime

is France in the 1780s, where the fiscal crisis contributed to the domestic political crisis.

These American trade and federal deficits are now interacting with a new phenomenon in the world economy—what is perhaps best described as the “dislocation” of international capital movements from the trade in goods and services. Because of the growing integration of the world economy, the volume of trade both in manufactures and in financial services is much larger than ever before, and together may amount to some $3 trillion a year; but that is now eclipsed by the stupendous level of capital flows pouring through the world’s money markets, with the London-based Eurodollar market alone having a volume “at least 25 times that of world trade.”

239

While this trend was fueled by events in the 1970s (the move from fixed to floating exchange rates, the surplus funds flowing from OPEC countries), it has also been stimulated by the U.S. deficits, since the only way the federal government has been able to cover the yawning gap between its expenditures

and its receipts has been to suck into the country tremendous amounts of liquid funds from Europe and (especially) Japan—turning the United States, as mentioned above, into the world’s largest debtor country by far.

240

It is, in fact, difficult to imagine how the American economy could have got by

without

the inflow of foreign funds in the early 1980s, even if that had the awkward consequence of sending up the exchange value of the dollar, and further hurting U.S. agricultural and manufacturing exports. But that in turn raises the troubling question about what might happen if those massive and volatile funds were pulled out of the dollar, causing its value to drop precipitously.

The trends have, in turn, produced explanations which suggest that alarmist voices are exaggerating the gravity of what is happening to the U.S. economy and failing to note the “naturalness” of most of these developments. For example, the midwestern farm belt would be much less badly off had not so many individuals bought land at inflated prices and excessive interest rates in the late 1970s. Again, the move from manufacturing into services is an understandable one, which is occurring in all advanced countries; and it is also worth recalling that U.S. manufacturing

output

has been rising in absolute terms, even if employment (especially blue-collar employment) in manufacturing industry has been falling—but that again is a “natural” trend, as the world increasingly moves from material-based to knowledge-based production. Similarly, there is nothing wrong in the metamorphosis of American financial institutions into

world

financial institutions, with a triple base in Tokyo, London, and New York, to handle (and profit from) the great volume of capital flows; that can only boost the nation’s earnings from services. Even the large annual federal deficits and the mounting national debt are sometimes described as being not too serious, after allowance is made for inflation; and there exists in some quarters a belief that the economy will “grow its way out” of these deficits, or that measures will be taken by the politicians to close the gap, whether by increasing taxes or cutting spending or a combination of both. A too-hasty attempt to slash the deficit, it is pointed out, could well trigger off a major recession.

Even more reassuring are said to be the positive signs of growth in the American economy. Because of the boom in the services sector, the United States has been creating jobs over the past decade faster than at any time in its peacetime history—and certainly a lot faster than in western Europe. As a related point, its far greater degree of labor mobility eases such transformations in the job market. Furthermore, the enormous American commitment in high technology—not just in California, but in New England, Virginia, Arizona, and many other parts of the land—promises ever greater outputs of production, and thus of national wealth (as well as ensuring a strategical edge over the USSR). Indeed, it is precisely because of the opportunities that exist in

the American economy that it continues to attract millions of immigrants, and to stimulate thousands of new entrepreneurs; while the floods of capital which pour into the country can be tapped for further investment, especially into R&D. Finally, if the shifts in the global terms of trade are indeed leading to lower prices for foodstuffs and raw materials, that ought to benefit an economy which still imports enormous amounts of oil, metal ores, and so on (even if it hurts particular American producers, like farmers and oilmen).

Many of these individual points may be valid. Since the American economy is so large and variegated, some sectors and regions are likely to be growing at the same time as others are in decline—and to characterize the whole with sweeping generalizations about “crisis” or “boom” is therefore inappropriate. Given the decline in raw-materials prices, the ebbing of the dollar’s unsustainably high exchange value of early 1985, the general fall in interest rates—and the impact of all three trends upon inflation and upon business confidence—it is not surprising to find some professional economists being optimistic about the future.

241

Nevertheless, from the viewpoint of American grand strategy, and of the economic foundation upon which an effective, long-term strategy needs to rest, the picture is much less rosy. In the first place, given the worldwide array of military liabilities which the United States has assumed since 1945, its capacity to carry those burdens is obviously less than it was several decades ago, when its share of global manufacturing and GNP was much larger, its agriculture was not in crisis, its balance of payments was far healthier, the government budget was also in balance, and it was not so heavily in debt to the rest of the world. In that larger sense, there is something in the analogy which is made by certain political scientists between the United States’ position today and that of previous “declining hegemons.”

242

Here again, it is instructive to note the uncanny similarities between the growing mood of anxiety among thoughtful circles in the United States today and that which pervaded all political parties in Edwardian Britain and led to what has been termed the “national efficiency” movement: that is, a broad-based debate within the nation’s decision-making, business, and educational elites over the various measures which could reverse what was seen to be a growing uncom-petitiveness as compared with other advanced societies. In terms of commercial expertise, levels of training and education, efficiency of production, standards of income and (among the less well-off) of living, health, and housing, the “number-one” power of 1900 seemed to be losing its position, with dire implications for the country’s long-term

strategic

position; hence the fact that the calls for “renewal” and “reorganization” came at least as much from the Right as from the Left.

243

Such campaigns usually do lead to reforms, here and there; but

their very existence is, ironically, a confirmation of decline, in that such an agitation simply would not have been necessary a few decades earlier, when the nation’s lead was unquestioned. A strong man, the writer G. K. Chesterton sardonically observed, does not worry about his bodily efficiency; only when he weakens does he begin to talk about health.

244

In the same way, when a Great Power is strong and unchallenged, it will be much less likely to debate its capacity to meet its obligations than when it is relatively weaker.

More narrowly, there could be serious implications for American grand strategy if its industrial base continued to shrink. Were there ever to be a large-scale future war which remained conventional (because of the belligerents’ mutual fear of triggering a nuclear holocaust), then one is bound to wonder what the impact upon U.S. productive capacities would be after years of decline in certain key industries, the erosion of blue-collar employment, and so on. In this connection, one is reminded of Hewins’s alarmed cry in 1904 about the impact of British industrial decay upon

that

country’s power:

245