The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (67 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

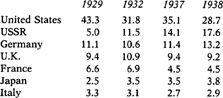

Table 30. Shares of World Manufacturing Output, 1929-1938

155

(percent)

By 1937 and 1938, however, Roosevelt himself seems to have become more worried by the fascist threats, even if American public opinion and economic difficulties restrained him from taking the lead. His messages to Berlin and Tokyo became firmer, his encouragement of Britain and France somewhat warmer (even if that hardly helped those two democracies in the short term). By 1938, secret Anglo-American naval talks were taking place about how to deal with the twin challenges of Japan and Germany. The president’s “quarantine” speech was an early sign that he would move toward economic discrimination

against the dictator states. Above all, Roosevelt now pressed for large-scale increases in defense expenditures. As the figures in

Table 26

above show, even in 1938 the United States was spending less on armaments than Britain or Japan, and only a fraction of the sums spent by Germany and the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, aircraft production virtually doubled between 1937 and 1938, and in the latter year Congress passed a “Navy Second to None” Act, allowing for a massive expansion in the fleet. By that time, too, tests were taking place on the prototype B-17 bomber, the Marines Corps was refining its doctrine of amphibious warfare, and the army (while not yet possessing a decent tank) was grappling with the problems of armored warfare and planning to mobilize a vast force.

159

When war broke out in Europe, none of the services was at all ready; but they were in better shape, relative to the demands of modern warfare, than they had been in 1914.

Even these rearmament measures scarcely disturbed an economy the size of the United States. The key fact about the American economy in the late 1930s was that it was greatly

underutilized

. Unemployment was around ten million in 1939, yet industrial productivity per man-hour had been vastly improved by investments in conveyor belts, electric motors (in place of steam engines), and better managerial techniques, although little of this showed through in

absolute

output figures because of the considerable reduction in work hours by the labor force. Given the depressed demand, which the 1937–1938 recession did not help, the various New Deal schemes were insufficient to stimulate the economy and take advantage of this underutilized productive capacity. In 1938, for example, the United States produced 26.4 million tons of steel, well ahead of Germany’s 20.7 million, the USSR’s 16.5 million, and Japan’s 6.0 million; yet the steel industries of those latter three countries were working to full capacity, whereas

two-thirds

of American steel plants were idle. As it turned out, this un-derutilization was soon going to be changed by the enormous rearmament programs.

160

The 1940 authorization of a doubling (!) of the navy’s combat fleet, the Army Air Corps’ plan to create eighty-four groups with 7,800 combat aircraft, the establishment (through the Selective Service and Training Act) of an army of close to 1 million men—all had an effect upon an economy which was not, like those of Italy, France, and Britain, suffering from severe structural problems, but was merely underutilized because of the Depression. Precisely because the United States had an enormous spare capacity whereas other economies were overheating, perhaps the most significant statistics for understanding the outcome of the future struggle were not the 1938 figures of actual steel or industrial output, but those which attempt to measure national income (

Table 31

) and, however imprecise, “relative war potential” (

Table 32

). For in each case they remind us that if the United States had suffered disproportionately during the Great

Depression, it nonetheless remained (in Admiral Yamamoto’s words) a sleeping giant.

Table 31. National Income of the Powers in 1937 and Percentage Spent on Defense

161

| | National Income (billions of dollars) | Percentage on Defense |

| United States | 68 | 1.5 |

| British Empire | 22 | 5.7 |

| France | 10 | 9.1 |

| Germany | 17 | 23.5 |

| Italy | 6 | 14.5 |

| USSR | 19 | 26.4 |

| Japan | 4 | 28.2 |

Table 32. Relative War Potential of the Powers in 1937

162

| United States | 41.7% |

| Germany | 14.4% |

| USSR | 14.0% |

| U.K. | 10.2% |

| France | 4.2% |

| Japan | 3.5% |

| Italy | 2.5% |

| | (seven Powers 90.5%) |

The awakening of this giant after 1938, and especially after 1940, provides a final confirmation the crucial issue of

timing

in the arms races and strategical calculations of this era. Like Britain and the USSR a little earlier, the United States was now endeavoring to close the armaments gap which had been opened up by the prior and heavy defense spending of the fascist states. That it could outspend any other country, if the political will existed at home, was clear from the statistics: even as late as 1939, U.S. defense composed only 11.7 percent of total expenditures and a mere 1.6 percent of GNP

163

—percentages far, far less than in any of the other Great Powers. An increase in the defense-spending share of the American GNP to bring it close to the proportions devoted to armaments by the fascist states would automatically make the United States the most powerful military state in the world. There are, moreover, many indications that Berlin and Tokyo realized how such a development would constrict their opportunities for future expansion. In Hitler’s case, the issue is complicated by his scorn for the United States as a degenerate, miscegenated power, but he also sensed that he dared not wait until the mid-1940s to resume his conquests, since the military balance would by then have decisively swung to the Anglo-French-American camp.

164

On the Japanese side, because the United States was taken more seriously, the calculations

were more precise: thus, the Japanese navy estimated that whereas its warship strength would be a respectable 70 percent of the American navy in late 1941, “this would fall to 65 percent in 1942, to 50 percent in 1943, and to a disastrous 30 percent in 1944.”

165

Like Germany, Japan also had a powerful strategical incentive to move soon if it was going to escape from its fate as a middleweight nation in a world increasingly overshadowed by the superpowers.

When the relative strengths and weaknesses of each of the Great Powers are viewed in their entirety, and also integrated into the economic and technological-military dynamics of the age, the course of international diplomacy during the 1930s becomes more comprehensible. This is not to imply that the

local

roots of the various crises—whether in Mukden, Ethiopia, or the Sudetenland—were completely irrelevant, or that there would have been no international problems if the Great Powers had been in harmony. But it is clear that when a regional crisis arose, the statesmen in each of the leading capitals were compelled to view such events in the light both of the larger diplomatic scene and, perhaps especially, of their pressing domestic problems. The British prime minister, MacDonald, put this nicely to his colleague Baldwin, after the 1931 Manchurian affair had interacted with the sterling crisis and the collapse of the second Labor government:

We have all been so distracted by day to day troubles that we never had a chance of surveying the whole situation and hammering out a policy regarding it, but have had to live from agitation to agitation.

166

It is a good reminder of the way politicians’ concerns were often immediate and practical, rather than long-term and strategic. But even after the British government had recovered its breath, there is no sign that it contemplated a change in its circumspect policy toward Japan’s conquest of Manchuria. Quite apart from the continued need to deal with economic problems, and the public’s unrelenting dislike of entanglements in the Far East, British leaders were also aware of dominion pressures for peace and of the very rundown state of imperial defenses in a region where Japan enjoyed the strategical advantage. In any case, there were various Britons who approved of Tokyo’s decision to deal with the irritating Chinese nationalists and many more who wanted to maintain good relations with Japan. Even when those sentiments waned, after further Japanese aggressions, the only way in which

Whitehall might be moved to stronger action would be in conjunction with the League and/or the other Great Powers.

But the League itself, however admirable its principles, had no effective means for preventing Japanese aggression in Manchuria other than the armed forces of its leading members. Thus its recourse to an investigative committee (the Lytton Commission) merely gave the Powers an excuse to delay action while at the same time Japan continued its conquest. Of the major states, Italy had no real interests in the Far East. Germany, although enjoying commercial and military ties with China, preferred to sit back and observe whether Japan’s “revisionism” could offer a useful precedent in Europe. The Soviet Union

was

concerned about Japanese aggression, but was unlikely to be invited to cooperate with the other powers and had no intention of being pushed forward alone. The French, predictably, were caught in a dilemma: they had no wish to see precedents being set for altering existing territorial boundaries and flouting League resolutions; on the other hand, being increasingly worried about clandestine German rearmament and the need to maintain the status quo in Europe, the French were appalled at the idea of complications arising in the Far East which would direct attention, and possibly military resources, away from the German problem. While Paris publicly stood firm alongside League principles, it privately let Tokyo know that it understood Japan’s problems in China.

167

By contrast, the U.S. government—at least as represented by Secretary of State Stimson—in no way condoned Japanese actions, rightly seeing in them a threat to the open-door world upon which, in theory, the American way of life was so dependent. But Stimson’s high-principled condemnations attracted neither Hoover, who feared the consequent entanglements, nor the British government, which preferred trimming to crusading. The result was a Stimson-Hoover quarrel in their respective memoirs, and (more significant) a legacy of mistrust between Washington and London. All this offered a depressing and convincing example of what one scholar has termed “the limits of foreign policy.”

168

Whether or not the Japanese military’s move into Manchuria in 1931 was carried out

169

without the home government’s knowledge was less important than the fact that this action succeeded, and was expanded upon, without the West being able to do anything substantial. The larger consequences were that the League had been shown to be an ineffective instrument for preventing aggression, and that the three western democracies were incapable of united action. This was also evident in the contemporaneous discussion at Geneva concerning land and air disarmament; here, of course, the United States was missing, but the Anglo-French differences over how to respond to German demands for “equality” and the continued British evasion of any guarantee to ease France’s fears meant that Hitler’s new regime could walk

out of the talks and denounce the existing treaties without fear of any retribution.

170

The revival of a German threat by 1933 placed further strains upon Anglo-French-American diplomatic cooperation at a time when the World Economic Conference had broken down and the three democracies were erecting their own currency and trading blocs. Although France was the more directly threatened by Germany, it was Britain which felt that its freedom of maneuver had been more substantially impinged upon. By 1934 both the Cabinet and its Defence Requirements Committee conceded that while Japan was the more immediate danger, Germany was the greater long-term threat. But since it was not possible to be strong against both, it was important to achieve a reconciliation in one of those regions. Whereas some circles favored improving relations with Japan so as to be better able to stand up to Germany, the Foreign Office argued that an Anglo-Japanese understanding in the Far East would ruin London’s delicate relations with the United States. On the other hand, it could be pointed out to those imperial and naval circles who wanted to give priority to strengthening British defenses in the Orient that it was impossible to turn one’s back upon French concern over German revisionism and (after 1935) fatal to ignore the growing threat from the Luftwaffe. For the rest of the decade the decision-makers in Whitehall sought to escape from this strategical dilemma of facing potential enemies at opposite ends of the globe.

171