The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (91 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

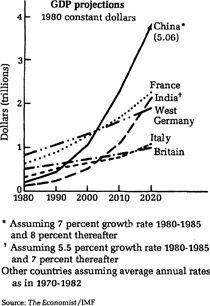

Chart 2. GDP Projections of China, India, and Certain Western European States, 1980–2020

The greatest mistake of all would be to assume that this sort of projection, with all the changeable factors that it rests upon, could ever work out with such exactitude. But the general point remains: China will have a very large GNP within a relatively short space of time, barring some major catastrophe; and while it will still be relatively poor in per capita terms, it will be decidedly richer than it is today.

Three further points are worth making about China’s future impact upon the international scene. The first, and least important for our purposes, is that while the country’s economic growth will boost its foreign trade, it is impossible to transform it into another West Germany or Japan. The sheer size of the domestic market of a continent-wide Power such as China, and of its population and raw-materials base, makes it highly unlikely that it would become as dependent upon

overseas commerce as one of the smaller, maritime “trading states.”

44

The extent of its labor-intensive agricultural sector and the regime’s determination not to become too reliant upon imported foodstuffs will also be a drag upon foreign trade. What is likely is that China will become an increasingly important producer of low-cost goods, like textiles, which will help to pay for western—or even Russian—technology; but Peking is clearly determined

not

to become dependent upon foreign capital, manufactures, or markets, or upon any one country or supplier in particular. Acquiring foreign technology, tools, and production methods will all be subject to the larger requirements of China’s balancing act. This is not contradicted by China’s recent membership in the World Bank and the IMF (and its possible future membership in GATT and the Asian Development Bank)—which are not so much indications of Peking’s joining the “free world” as they are of its hard-nosed calculation that it may be better to gain access to foreign markets, and to long-term loans, via international bodies than through unilateral “deals” with a Great Power or private banks. In other words, such moves protect China’s status and independence. The second point is separate from, but interrelates with, the first. It is that whereas in the 1960s Mao’s regime seemed almost to relish the frequent border clashes, Peking now prefers to maintain peaceful relations with its neighbors, even those it regards with suspicion. As noted above, peace is central to Deng’s economic strategy; war, even of a regional sort, would divert resources into the armed services and alter the order of priority among China’s “four modernizations.” It may also be the case, as has been argued recently,

45

that China feels more relaxed about relations with Moscow simply because its own military improvements have created a rough equilibrium in central Asia. Having achieved a “correlation of forces,” or at least a decent defensive capacity, China can concentrate more upon economic development.

Yet if its intentions are peaceable, China also emphasizes how determined it is to preserve its own complete independence, and how much it disapproves of the two superpowers’ military interventions abroad. Even toward Japan the Chinese have kept a wary eye, restricting its share of the import/export trade and yet also warning Tokyo not to get too heavily involved in developing Siberia.

46

Toward Washington and Moscow, China has been much more studied—and critical. All of the Soviet suggestions for improving relations and even the return of Soviet engineers and scientists to China in early 1986 have not altered Peking’s fundamental position: that a real improvement cannot take place until Moscow makes concessions in some, if not all, of the three outstanding issues—the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, the Russian support of Vietnam, and the long-standing question of central Asian boundaries and security.

47

On the other hand, U.S. policies in Latin America and the Middle East have come in for repeated

attack from Peking (as, to be sure, have similar Russian adventures in the tropics). Being economically one of the “less-developed countries” and inherently suspicious of the white races’ domination of the globe makes China a natural critic of superpower intervention, even if it is not a formal member of the Third World movement and even if those criticisms are nowadays fairly mild compared to Mao’s fulminations of the 1960s. And despite its earlier (and still powerful) hostility to Russian pretensions in Asia, the Chinese remain suspicious of the earnest American discussion of how and when to play the “China card.”

48

In Peking’s view, it may be necessary to incline toward Russia or (more frequently, since the Sino-Soviet quarrels) toward the United States, by measures including the joint monitoring of Russian nuclear testing and exchanging information over Afghanistan and Vietnam; but the ideal position is to be equidistant between the two, and to have them both wooing the Middle Kingdom.

To this extent, China’s importance as a truly independent actor in the present (and future) international system is enhanced by what, for want of a better word, one might term its “style” of relating to the other Powers. This has been put so nicely by Jonathan Pollack that it is worth repeating

in extenso:

[W]eapons, economic strength, and power potential alone cannot explain the imputed significance of China in a global power equation. If its strategic significance is judged modest and its economic performance has been at best mixed, this cannot account for the considerable importance of China in the calculations of both Washington and Moscow, and the careful attention paid to it in other key world capitals. The answer lies in the fact that, notwithstanding its self-characterization as a threatened and aggrieved state, China has very shrewdly and even brazenly used its available political, economic, and military resources. Towards the superpowers, Peking’s overall strategy has at various times comprised confrontation and armed conflict, partial accommodation, informal alignment, and a detachment bordering on disengagement, sometimes interposed with strident, angry rhetoric. As a result, China becomes all things to all nations, with many left uncertain and even anxious about its long-term intentions and directions.

To be sure, such an indeterminate strategy has at times entailed substantial political and military risks. Yet the same strategy has lent considerable credibility to China’s position as an emergent major power. China has often acted in defiance of the preferences or demands of both superpowers; at other times it has behaved far differently from what others expect. Despite its seeming vulnerability, China has not proven pliant and yielding toward either Moscow or Washington.… For all these reasons, China has assumed a singular international position, both as a participant in many of the central political and military conflicts in the post war era and as a

State that resists easy political or ideological categorization.… Indeed, in a certain sense China must be judged as a candidate superpower in its own right—not in imitation or emulation of either the Soviet Union or the United States, but as a reflection of Peking’s unique position in global politics. In a long-term sense, China represents a political and strategic force too significant to be regarded as an adjunct to either Moscow or Washington or simply as an intermediate power.

49

As a final point, it needs to be stressed again that although China is keeping a tight hold upon military expenditures at the moment, it has no intention of remaining a strategical “lightweight” in the future. On the contrary, the more that China pushes forward with its economic expansion in a Colbertian,

étatiste

fashion, the more that development will have power-political implications. This is the more likely when one recalls the attention China is giving to expanding its scientific/technological base, and the impressive achievements already made in rocketry and nuclear weapons when that base was so much smaller. Such a concern for enhancing the country’s economic substructure at the expense of an immediate investment in weapons will hardly satisfy China’s generals (who, like military groups everywhere, prefer short-term to long-term means of security). Yet as

The Economist

has nicely remarked:

For [China’s] military men with the patience to see the [economic] reforms through, there is a payoff. If Mr. Deng’s plans for the economy as a whole are allowed to run their course, and the value of China’s output quadruples, as planned, between 1980 and 2000 (admittedly big ifs), then 10 to 15 years down the line the civilian economy should have picked up enough steam to haul the military sector along more rapidly. That is when China’s army, its neighbors and the big powers will really have something to think about.

50

It is only a matter of time.

The very fact that Peking is so purposeful about what is to happen in East Asia increases the pressures now bearing down upon Japan’s (self-proclaimed) “omnidirectional peaceful diplomacy”—or what might more cynically be described as “being all things to all men.”

51

The Japanese dilemma may perhaps be best summarized as follows:

Due to its immensely successful growth since 1945, the country enjoys a unique and very favorable position in the global economic and power-political order, yet that is also—the Japanese feel—an extremely

delicate and vulnerable position, which could be badly deranged if international circumstances changed. The best thing that could happen from Tokyo’s viewpoint, therefore, would be for the continuation of those factors which caused “the Japanese miracle” in the first place. But precisely because this is an anarchic world in which “dissatisfied” powers jostle alongside “satisfied” ones, and because the dynamic of technological and commercial change is driving so fast, the likelihood is that those favorable factors will diminish—or even disappear altogether. Given Japan’s belief in the delicacy and vulnerability of its own position, it finds it hard openly to resist the pressures for change; instead, the latter must be slowed down, or deflected, by diplomatic compromise. Hence its constant advocacy of the peaceful solution to international problems, its alarm and embarrassment when it finds itself in a political crossfire between other countries, and its evident wish to be on good terms with everyone while it gets steadily richer.

The reasons for Japan’s phenomenal economic success have already been discussed (see above, pp. 416–18). For over forty years the Japanese homeland has been protected by American nuclear and conventional forces, and its sea lanes by the U.S. Navy. Thus enabled to redirect its national energies from militaristic expansion and its resources from high defense spending, Japan has devoted itself to the pursuit of sustained economic growth, especially in export markets. This success could not have been achieved without its own people’s commitment to entrepreneurship, quality control, and hard work, but it was also aided by certain special factors: the holding-down of the yen to an artificially low level for decade after decade in order to boost exports; the restrictions, both formal and informal, upon the purchase of imported foreign manufactures (although not, of course, of the vital raw materials which industry needed); and the existence of a liberal international trading order which placed few obstacles in the way of Japanese goods—and which was kept “open,” despite the increasing burdens upon itself, by the United States. For the past quarter-century, therefore, Japan has been able to enjoy all of the advantages of evolving into a global economic giant, but without any of the political responsibilities and territorial disadvantages which have, historically, followed from such a growth. Little wonder that it prefers things to remain as they are.

Since the foundations of Japan’s present success lie exclusively in the economic sphere, it is not surprising that this also is the field which worries Tokyo most. On the one hand (as will be discussed below), technological and economic growth offers fresh glittering prizes to the country whose political economy is best positioned for the coming twenty-first century; and only a few dispute the contention that Japan is in that favorable position.

52

On the other hand, its very success is already provoking a “scissors effect” reaction against its export-led

expansion. The one “blade” of those scissors is the emulation of Japan by other ambitious Asian NICs (newly industrialized countries), such as South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, etc.—not to mention China itself at the lower end of the product scale (e.g., textiles).

53

All of these countries have far lower labor costs than Japan,

*

and are challenging strongly in fields in which the Japanese no longer enjoy decisive advantages—textiles, toys, domestic goods, shipbuilding, even (to a much less degree) steel and automobiles. This does not, of course, mean that Japan’s production of ships, cars, trucks, and steel is doomed, but to the extent that it is increasingly necessary for them to move “up-market” (e.g., to higher-grade steels, or more sophisticated and larger-sized automobiles) they are withdrawing from the bottom end of a production spectrum where previously they were unchallenged; and one of the more important tasks of MITI (the Ministry for International Trade and Industry) is to plan the phasing out of industries which are no longer competitive—not only to make the decline less traumatic but also to arrange for the transfer of resources and personnel into other, more competitive sectors of the international economy.