The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (87 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

As the 1960s unfolded, however, this cozy situation evaporated. Both Kennedy and (even more) Johnson were willing to increase American military expenditures overseas, and not just in Vietnam, although that conflict turned the flow of dollars exported into a flood. Both Kennedy and (even more) Johnson were committed to increases in domestic expenditures, a trend already detectable prior to 1960. Neither administration liked the political costs of raising taxes to pay for the inevitable inflation. The result was year after year of federal government deficits, soaring price rises, and increasing American industrial uncompetitiveness—in turn leading to larger balance-of-payments deficits, the choking back (by the Johnson administration) of foreign investments by U.S. firms, and then the latter’s turn toward the new instrument of Eurodollars. In the same period, the U.S. share of world (non-Comecon) gold reserves shrank remorselessly, from 68 percent (1950) to a mere 27 percent (1973). With the entire international payments and money-flow system buckling under these interacting problems, and being further weakened by de Gaulle’s angry counterattacks against what he regarded as America’s “export of inflation,” the Nixon administration found it had little choice but to end the dollar’s link to gold in private markets, and then to float the dollar against other currencies. The Bretton Woods system, very much a creation of the days when the United States was financially supreme, collapsed when its leading pillar could bear the strains no more.

253

The detailed story of the ups and downs of the dollar in the 1970s, when it was floating freely, are not for telling here; nor is the zigzag course of successive administrations’ efforts to check inflation and to stimulate growth, always without causing too much pain politically. The higher-than-average inflation in the United States generally caused the dollar to weaken vis-à-vis the German and Japanese currencies in the 1970s; oil shocks, which hurt countries more dependent upon OPEC supplies (e.g., Japan, France), political turbulence in various parts of the world, and high American interest rates tended to push the dollar upward, as was the case by the early 1980s. Yet although these oscillations were important, and tended to add to global economic insecurities, they may be less significant for our purposes than the unrelenting longer-term trends, which were the decreasing productivity growth, which in the private sector fell from 2.4 percent (1965–1972), to 1.6 percent (1972–1977), to 0.2 percent (1977–1982);

254

the increasing federal deficits, which could be seen as giving a Keynesian-type

“boost” to the economy, but at the cost of sucking in so much cash from abroad (attracted by the higher American interest rates) that it sent the dollar’s price to artificially high levels and turned the country from a net lender to a net borrower; and the increasing difficulty American manufacturers found in competing with imported automobiles, electrical goods, kitchenware, and other manufactures. Not surprisingly, American per capita GNP, once the highest in the world, began to slip down the list.

255

There were still consolations, to those who could see the American economy and its needs in larger terms than selected comparisons with Swiss incomes or Japanese productivity. As Calleo points out, post-1945 American policy did achieve some very basic and significant aims: domestic prosperity, as opposed to a 1930s-type slump; the containing of Soviet expansionism without war; the revival of the economies—and the democratic traditions—of western Europe, later joined by Japan to create “an increasingly integrated economic bloc,” with “an imposing battery of multilateral institutions … to manage common economic as well as military affairs”; and, finally, “the transformation of the old colonial empires into independent states still closely integrated into a world economy.”

256

In sum, it had maintained the liberal international order, upon which it, itself, increasingly depended; and while its share of world production and wealth had shrunk, perhaps faster than need have been the case, the redistribution of global economic balances still left an environment which was not too hostile to its own open-market and capitalist traditions. Finally, if it had seen its productive lead eroded by certain faster-growing economies, it had still maintained a very considerable superiority over the Soviet Union in almost all respects of true national power and—by clinging to its own entrepreneurial creed—remained open to the stimulus of managerial initiative and technological charge which its Marxist rival would have far greater difficulty in accepting.

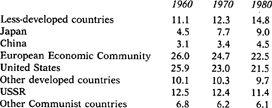

A more detailed discussion of the implication of these economic movements must await the final chapter. It may, however, be useful to give in statistical form (see

Table 43

) the essence of the trends examined above, as they concern the global economic balances, namely the partial recovery of the share of world product in the hands of the less-developed countries; the remarkable growth of Japan and, to a lesser extent, of the People’s Republic of China; the erosion of the European Economic Community’s share even as it remained the largest economic bloc in the world; the stabilization, and then slow decline, of the USSR’s share; and the much faster decline, but still far larger economic muscle, of the United States.

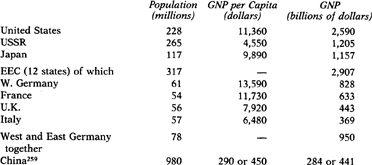

Indeed, by 1980, the final year in

Table 43

, the World Bank’s figures of population, GNP per capita, and GNP itself, were very much pointing

to a

multipolar

distribution of the global economic balances, as shown in

Table 44

.

Table 43. Shares of Gross World Product, 1960-1980

257

(percent)

Table 44. Population, GNP per Capita, and GNP in 1980

258

259

Finally, it might be useful to recall that these long-term shifts in the productive balances are of importance not so much for their own sake, but for their power-political implications. As Lenin himself noted in 1917–1918, it was the

uneven

economic growth rates of countries which led ineluctably to the rise of specific powers and the decline of others:

Half a century ago, Germany was a miserable, insignificant country, as far as its capitalist strength was concerned, compared with the strength of England at that time. Japan was similarly insignificant compared with Russia. Is it “conceivable” that in ten or twenty years’ time the relative strength of the imperialist powers will have remained

un

changed? Absolutely inconceivable.

260

And for all Lenin’s own concentration upon the capitalist imperialist states, the rule seems common to

all

national units, whatever their favored political economy, that uneven rates of economic growth

would, sooner or later, lead to shifts in the world’s political and military balances. This, certainly, has been the pattern observed in the four centuries of Great Power development prior to the present one. It therefore follows that the unusually rapid shifts in the centers of world production during the past two or three decades cannot avoid having repercussions upon the grand-strategical future of today’s leading Powers, and rightly deserve the attention of one final chapter.

To the Twenty-first Century

A chapter with a title such as that above implies not merely a change in chronology but also, and much more significantly, a change in

methodology

. Even the very recent past is history, and although problems of bias and source make the historian of the previous decade “hard put to separate the ephemeral from the fundamental,”

1

he is still operating within the same academic discipline. But writings upon how the present may evolve into the future, even if they discuss trends which are already under way, can lay no claim to being historical truth. Not only do the raw materials change, from archivally based monographs to economic

forecasts

and political

projections

, but the validity of what is being written about can no longer be assumed. Even if there always were many methodological difficulties in dealing with “historical facts,”

2

past events like an archduke’s assassination or a military defeat

did indeed occur

. Nothing one can say about the future has that certainty. Unforeseen happenings, sheer accidents, the halting of a trend, can ruin the most plausible of forecasts; if they do not, then the forecaster is merely lucky.

What follows, then, can only be provisional and conjectural, based upon a reasoned surmise of how present tendencies in global economics and strategy may work out—but with no guarantee that all (or any) of this will happen. The gyrations which have occurred in the international value of the dollar over the past few years and the post-1984 collapse in oil prices (with its differing implications, for Russia, for Japan, for OPEC) offer a good warning against drawing conclusions from economically based trends; and the world of politics and diplomacy has never been one which followed straight lines. Many a final chapter in works dealing with contemporary affairs has to be changed, only a few years later, in the wisdom of hindsight; it will be surprising if this present chapter survives unscathed.

Perhaps the best way to comprehend what lies ahead is to look

backward

briefly, at the rise and fall of the Great Powers over the past five centuries. The argument in this book has been that there exists a dynamic for change, driven chiefly by economic and technological developments, which then impact upon social structures, political systems, military power, and the position of individual states and empires. The speed of this global economic change has not been a uniform one, simply because the pace of technological innovation and economic growth is itself irregular, conditioned by the circumstance of the individual inventor and entrepreneur as well as by climate, disease, wars, geography, the social framework, and so on. In the same way, different regions and societies across the globe have experienced a faster

or

slower rate of growth, depending not only upon the shifting patterns of technology, production, and trade, but also upon their receptivity to the new modes of increasing output and wealth. As some areas of the world have risen, others have fallen behind—relatively or (sometimes) absolutely. None of this is surprising. Because of man’s innate drive to improve his condition, the world has never stood still. And the intellectual breakthroughs from the time of the Renaissance onward, boosted by the coming of the “exact sciences” during the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution, simply meant that the dynamics of change would be increasingly more powerful and self-sustaining than before.

The second major argument of this book has been that this uneven pace of economic growth has had crucial long-term impacts upon the relative military power and strategical position of the members of the states system. This again is unsurprising, and has been said many times before, although the emphasis and presentation of argument may have been different.

3

The world did not need to wait until Engels’s time to learn that “nothing is more dependent on economic conditions than precisely the army and the navy.”

4

It was as clear to a Renaissance prince as it is to the Pentagon today that military power rests upon adequate supplies of wealth, which in turn derive from a flourishing productive base, from healthy finances, and from superior technology. As the above narrative has shown, economic prosperity does not

always and immediately

translate into military effectiveness, for that depends upon many other factors, from geography and national morale to generalship and tactical competence. Nevertheless, the fact remains that all of the major shifts in the world’s

military-power

balances have followed alterations in the

productive

balances; and further, that the rising and falling of the various empires and states in the international system has been confirmed by the outcomes of the major Great Power wars, where victory has always gone to the side with the greatest material resources.