The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (83 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

Table 39. Production of World Manufacturing Industries, 1830–1980

192

(1900 = 100)

| | Total Production | Annual Growth Rate |

| 1830 | 34.1 | (0.8) |

| 1860 | 41.8 | 0.7 |

| 1880 | 59.4 | 1.8 |

| 1900 | 100.0 | 2.6 |

| 1913 | 172.4 | 4.3 |

| 1928 | 250.8 | 2.5 |

| 1938 | 311.4 | 2.2 |

| 1953 | 567.7 | 4.1 |

| 1963 | 950.1 | 5.3 |

| 1973 | 1730.6 | 6.2 |

| 1980 | 3041.6 | 2.4 |

As Bairoch also points out, “The accumulated world industrial output between 1953 and 1973 was comparable in volume to that of the entire century and a half which separated 1953 from 1800.”

193

The recovery of war-damaged economies, the development of new technologies, the continued shift from agriculture to industry, the harnessing of national resources within “planned economies,” and the spread of industrialization to the Third World all helped to effect this dramatic change.

In an even more emphatic way, and for much the same reasons, the volume of world trade also grew spectacularly after 1945, in contrast to the distortions of the era of the two world wars:

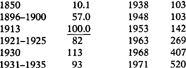

Table 40. Volume of World Trade, 1850-1971

194

(1913 = 100)

What was more encouraging, as Ashworth points out, was that by 1957, for the first time ever world trade in manufactured goods exceeded those in primary produce, which itself was a consequence of the fact that the increase in the overall output of manufactures during these decades was considerably larger than the (very impressive) increases in agricultural goods and minerals (see

Table 41

).

Table 41. Percentage Increases in World Production, 1948–1968

195

| | 1948–1958 | 1958–1968 |

| Agricultural goods | 32% | 30% |

| Minerals | 40% | 58% |

| Manufactures | 60% | 100% |

To some extent, this disparity can be explained by the great increases in manufacturing and trade

among

the advanced industrial countries (especially those of the European Economic Community); but their rising demand for primary products and the beginnings of industrialization among an increasing number of Third World countries meant that the economies of most of the latter were also growing faster in these decades than at any time in the twentieth century.

196

Notwithstanding the damage which western imperialism did to many of the societies in other parts of the world, the exports and general economic growth of these societies do appear to have benefited most when the industrialized nations were in a period of expansion. Less-developed countries (LDCs), argues Foreman-Peck, grew rapidly in the nineteenth century when “open” economies like Britain’s were expanding fast—just as they were the worst hit of all when the industrial world fell into depression in the 1930s. During the 1950s and 1960s, they once again experienced faster growth rates, because the developed countries were booming, raw-materials demand was rising, and industrialization was spreading.

197

After its nadir in 1953 (6.5 percent), Bairoch shows the Third World’s share of world manufacturing production rising steadily, to 8.5 percent (1963), then 9.9 percent (1973), and then 12.0 percent (1980).

198

In the CIA’s estimates, the less-developed countries’ share of “gross world product” has also been increasing, from 11.1 percent (1960), to 12.3 percent (1970), to 14.8 percent (1980).

199

Given the sheer number of people in the Third World, however, their share of world product was still disproportionately low—and their poverty horrifically manifest. The average GNP per capita in the industrialized countries was $10,660 in 1980, but only $1,580 per capita for the middle-income countries like Brazil, and a shocking $250 per capita for the very poorest Third World countries like Zaire.

200

For the fact was that while their proportion of world product and manufacturing output was arising

as a whole

, the gain was not shared in equal

proportion by all of the LDCs. Differences in wealth between some countries in the tropics were large even as the colonialists withdrew—just as they had been, in many cases, before the imperial era. They were exacerbated by the uneven pattern of demand for the countries’ products, by the varying levels of aid which each managed to secure, and by the vicissitudes of climate, politics, tampering with the environment, and economic forces quite outside their control. Drought could devastate a country for years. Civil wars, guerrilla activities, or the forced resettlement of peasants could reduce agricultural output and trade. Sinking world prices, say, of peanuts or tin could almost bring a single-product economy to a halt. Soaring interest rates, or a rise in the value of the U.S. dollar, could be body blows. A spiraling population growth, caused by western medical science’s success in checking disease, increased the pressure upon food stocks and threatened to wipe out any gains in overall national income. On the other hand, there were states which went through a “green revolution,” with agricultural output boosted by improved farming techniques and new strains of plants. In addition, the massive earnings recorded by those countries lucky enough to possess oil in the 1970s turned them into a different economic category—although even these so-called OPEC-LDCs suffered as oil prices tumbled in the early 1980s. Finally, in one of the most significant developments of all, there arose among Third World countries a number of what Rosecrance terms “the trading states”— South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia, imitating Japan, West Germany, and Switzerland in their entrepreneurship and commitment to produce industrial manufactures for the global market.

201

This disparity among less-developed nations points to the second major feature of macroeconomic change over the past few decades—the differential growth rates among the various nations of the globe, which was as true of the larger, industrialized Powers as it was of the smaller countries. Since this trend is the one which—on the record of the preceding centuries—has ultimately had the greatest impact upon the international power balances, it is worth examining in some detail how it affected the major nations in these decades.

There can be no doubt that the economic transformation of Japan after 1945 offered the most spectacular example of sustained modernization in these decades, outclassing almost all of the existing “advanced” countries as a commercial and technological competitor, and providing a model for emulation by the other Asian “trading states.” To be sure, Japan had already distinguished itself almost a century earlier by becoming the first Asian country to copy the West in both economic and—fatefully for itself—military and imperialist terms. Although badly damaged by the 1937–1945 war, and cut off from its traditional markets and suppliers, it possessed an industrial infrastructure which could be repaired and a talented, well-educated, and

socially cohesive population whose determination to improve themselves could now be channeled into peaceful commercial pursuits. For the few years after 1945, Japan was prostrate, an occupied territory, and dependent upon American aid. In 1950, the tide turned—ironically, to a large degree because of the heavy U.S. defense spending in the Korean War, which stimulated Japan’s export-oriented companies. Toyota, for example, was in danger of foundering when it was rescued by the first of the U.S. Defense Department’s orders for its trucks; and much the same happened to many other companies.

202

There was, of course, much more to the “Japanese miracle” than the stimulant of American spending during the Korean War and, again, during the Vietnam War; and the effort to explain exactly how the country transformed itself, and how others can imitate-its success, has turned into a miniature growth industry itself.

203

One major reason was its quite fanatical belief in achieving the highest levels of quality control, borrowing (and improving upon) sophisticated management techniques and production methods in the West. It benefited from the national commitment to vigorous, high-level standards of universal education, and from possessing vast numbers of engineers, of electronics and automobile buffs, and of small but entrepreneurial workshops as well as the giant

zaibatsu

. There was social ethos in favor of hard work, loyalty to the company, and the need to reconcile management-worker differences through a mixture of compromise and deference. The economy required enormous amounts of capital to achieve sustained growth, and it received just that—partly because there was so little expenditure upon defense by a “demilitarized” country sheltering under the American strategic umbrella, but perhaps even more because of fiscal and taxation policies which encouraged an unusually high degree of personal savings, which could then be used for investment purposes. Japan also benefited from the role played by MITI (its Ministry for International Trade and Industry) in “nursing new industries and technological developments while at the same time coordinating the orderly run-down of aging, decaying industries,”

204

all this in a manner totally different from the American laissez-faire approach.

Whatever the mix of explanations—and other experts upon Japan would point more strongly to cultural and sociological reasons, not to mention that indefinable “plus factor” of national self-confidence and willpower in a people whose time has come—there was no denying the extent of its economic success. Between 1950 and 1973 its gross domestic product grew at the fantastic average of 10.5 percent a year, far in excess of that of any other industrialized nation; and even the oil crisis in 1973–1974, with its profound blow to world expansion, did not prevent Japan’s growth rates in subsequent years from staying almost twice as large as those of its major competitors. The range of manufactures in which Japan steadily became the dominant world producer

was quite staggering—cameras, kitchen goods, electrical products, musical instruments, scooters, on and on the list goes. Japanese products challenged the Swiss watch industry, overshadowed the German optical industry, and devastated the British and American motorcycle industries. Within a decade, Japan’s shipyards were producing over half of the world’s tonnage of launchings. By the 1970s, its more modern steelworks were turning out as much as the American steel industry. The transformation of its automobile industry was even more dramatic—between 1960 and 1984 its share of world car production rose from 1 percent to 23 percent—and in consequence Japanese cars and trucks were being exported in their millions all over the world. Steadily, relentlessly, the country moved from low-to high-technology products—to computers, telecommunications, aerospace, robotics, and biotechnology. Steadily, relentlessly, its trade surpluses increased—turning it into a financial giant as well as an industrial one—and its share of world production and markets expanded. When the Allied occupation ended in 1952, Japan’s “gross national product was little more than one-third that of France or the United Kingdom. By the late 1970s the Japanese GNP was as large as the United Kingdom’s and France’s

combined

and more than half the size of America’s.”

205

Within one generation, its share of the world’s manufacturing output, and of GNP, had risen from around 2–3 percent to around 10 percent—and was not stopping. Only the USSR in the years after 1928 had achieved anything like that degree of growth, but Japan had done it far less painfully and in a much more impressive, broader-based way.

By comparison with Japan,

every

other large Power must seem economically sluggish. Nonetheless, when the People’s Republic of China (PRC) began to assert itself in the years after its foundation in 1949, there were few observers who did not take it seriously. In part this may have reflected a traditional worry about the “Yellow Peril,” since the sleeping giant in the East would clearly be a major force in world affairs just as soon as it had organized its 800 million population for national purposes. More important still was the very prominent, not to say aggressive, role which the PRC adopted toward foreign Powers almost since its inception, even if that may have been a nervous response to its perceived encirclement. The clashes with the United States over Korea and Quemoy and Matsu; the move into Tibet; the border struggles with India; the angry break with the USSR, and military confrontations in the disputed regions; the bloody encounter with North Vietnam; and the generally combative tone of Chinese propaganda (especially under Mao) as it criticized western imperialism and “Russian hegemonism” and urged on people’s liberation movements across the globe made it a much more important, but also more incalculable, figure in world affairs than the discreet and subtle Japanese.

206

Simply because China possessed one-quarter of the world’s population,

its political lurches in one direction or another had to be taken seriously.