The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (79 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

The relationship between the Third World and the “first two worlds” was always, therefore, a complex and shifting one. There were, to be sure, countries which were persistently pro-Russian (Cuba, Angola) and others which were strongly pro-American (Taiwan, Israel), chiefly because they felt under threat from their neighbors. There were some which, following Tito’s early lead, genuinely sought to be nona-ligned. There were others which, while leaning toward one bloc because it offered them aid, strongly resisted undue dependence. And, finally, there were the frequent revolutions, civil wars, changes of regime, and border conflicts in the Third World which took Moscow and Washington by surprise. Local rivalries in Cyprus, in the Ogaden, along the India-Pakistan border, and in Kampuchea (Cambodia) embarrassed the superpowers, since each of the contending parties sought their aid. Like other Great Powers before them, both Russia and the United States had to grapple with the hard fact that their “universalist”

message would not be automatically accepted by other societies and cultures.

As the 1960s moved into the 1970s, there nevertheless remained good reasons why the Washington-Moscow relationship should continue to seem all-important in world affairs. Militarily, the USSR had drawn much closer to the United States, but both were still in a different league from everyone else. In 1974, for example, the United States was spending $85 billion and the USSR was spending $109 billion on defense, which was three to four times what was spent by China ($26 billion) and eight to ten times what was spent by the leading European states (U.K. $9.7 billion; France, $9.9 billion; West Germany, $13.7 billion);

145

and the American and Russian armed forces, of over 2 million and 3 million men, respectively, were much larger than those of the European states, and much better equipped than the 3 million men in the Chinese services. Both superpowers had over 5,000 combat aircraft, more than ten times the number possessed by the former Great Powers.

146

Their total tonnage in warships—the United States had 2.8 million tons, the USSR 2.1 million tons in 1974—was well ahead of Britain (370,000 tons), France (160,000 tons), Japan (180,000 tons), and China (150,000 tons).

147

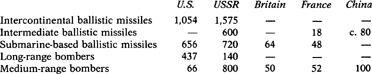

But the greatest disparity lay in the numbers of nuclear delivery weapons, shown in

Table 38

.

Table 38. Nuclear Delivery Vehicles of the Powers, 1974

148

So capable had each superpower become of obliterating the other (and anyone else besides)—a state of affairs quickly named MAD, or Mutually Assured Destruction—that they began to evolve arrangements for controlling the nuclear arms race in various ways. There was, following the Cuban missile crisis, the installation of a “hot line” to allow each side to communicate in the event of another critical occasion; there was the nuclear test-ban treaty of 1963, also signed by the United Kingdom, which banned testing in the atmosphere, under water, and in outer space; there was the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I) of 1972, which set limits on the numbers of intercontinental ballistic missiles each side could possess and halted the Russian

construction of an anti-ballistic-missile system; there was the extension of that agreement at Vladivostock in 1975, and, in the late 1970s, there were negotiations toward a SALT II treaty (signed in June 1979, but never ratified by the U.S. Senate). Yet these various measures of agreement, and the particular economic and domestic-political and foreign-policy motives which pushed each side into them, did not stop the arms race; if anything, the banning or limitation of one weapon system merely led to a transfer of resources to another area. From the late 1950s onward, the USSR steadily and inexorably increased its allocations to the armed forces; and while the pattern of American defense spending was distorted by its expensive war in Vietnam and then the public reaction against that venture, the long-term trend was also toward ever-higher totals. Every few years, newer weapon systems would be added: multiple warheads were fitted to each side’s rockets; missile-carrying submarines augmented each side’s navy; the nuclear stalemate in

strategic

missiles (provoking a European fear that the United States would not respond to a Soviet attack westward by unleashing long-range American missiles, since that could in turn provoke atomic strikes upon American cities) led to new types of medium-range or “theater” nuclear weapons, like the Pershing II and the cruise missiles being developed as answers to the Russian SS-20. The arms race and arms-control discussions of various sorts were obverse sides of the same coin; but each kept Washington and Moscow at the center of the stage.

In other fields, too, their rivalry appeared central. As mentioned earlier, one of the more notable features of the Soviet arms buildup since 1960 was the enormous expansion of its surface fleet—

physically

, as it constructed ever more powerful, missile-bearing destroyers and cruisers, then medium-sized helicopter carriers, then aircraft carriers;

149

and

geographically

, as the Soviet navy began to send more and more vessels into the Mediterranean and farther afield, to the Indian Ocean, West Africa, Indochina, and Cuba, where it was able to use an increasing number of bases. This last development reflected a very significant extension of American-Russian rivalries into the Third World, chiefly because of Moscow’s further success in breaking into regions where foreign influence had hitherto been a western monopoly. The continued tension in the Middle East, and especially the Arab-Israeli wars of 1967 and 1973 (where American arms supplies to Israel were decisive), meant that various Arab states—Syria, Libya, Iraq—would remain looking to Moscow for assistance. The Marxist regimes of Southern Yemen and Somalia provided naval-base facilities to the Russian navy, giving it a new maritime presence in the Red Sea. But, as usual, breakthroughs were accompanied by setbacks: Moscow’s apparent preference for Ethiopia led to the expulsion of Soviet personnel and ships from Somalia in 1977, just a few years after the same had

happened in Egypt; and Russian advances in this area were countered by the growth of the American presence in Oman and Diego Garcia, naval-base rights in Kenya and Somalia, and increased arms shipments to Egypt, Saudia Arabia, and Pakistan. Farther to the south, however, the Soviet-Cuban military assistance to the MPLA forces in Angola, the frequent attempts of the Soviet-aided Libyan regime of Qaddafi to export revolution elsewhere, and the presence of Marxist governments in Ethiopia, Mozambique, Guinea, Congo, and other West African states suggested that Moscow was winning in the struggle for global influence. Its own military move into Afghanistan in 1979— the first such expansion (outside eastern Europe) since the Second World War—and Cuba’s encouragement of leftist regimes in Nicaragua and Grenada furthered this impression that the American-Russian rivalry knew no limits, and provoked additional countermoves and increases in defense spending on Washington’s part. By 1980, with a new Republican administration denouncing the Soviet Union as an “evil empire” against which massive defense forces and unbending policies were the only answer, little seemed to have changed since the days of John Foster Dulles.

150

Yet, for all this focus upon the American-Russian relationship and its many ups and downs between 1960 and 1980, other trends had been at work to make the international power system much

less

bipolar than it had appeared to be in the earlier period. Not only had the Third World emerged to complicate matters, but significant fissures had occurred in what had earlier appeared to be the two monolithic blocs dominated by Moscow and Washington. The most decisive of these by far, with repercussions which are difficult to measure fully even at the present time, was the split between the USSR and Communist China. In retrospect, it may seem self-evident that even the allegedly “scientific” and “universalist” claims of Marxism would founder on the rocks of local circumstances, indigenous cultural strengths, and differing stages of economic development—after all, Lenin himself had had to make massive deviations from the original doctrine of dialectical materialism in order to secure the 1917 Revolution. And some foreign observers of Mao’s Communist movement in the 1930s and 1940s were aware that he, at least, was not inclined to adhere slavishly to Stalin’s dogmatic position toward the relative importance of workers and peasantry. They were also aware that Moscow, in its turn, had been less than wholehearted in its support of the Chinese Communist Party and had, even as late as 1946 and 1948, tried to balance it off against Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists. This, in the USSR’s view, would avoid the creation of “a vigorous new Communist regime established without the assistance of the Red Army in a country with almost three times the population of Russia [which] would inevitably become a competing pole of attraction within the world Communist movement.”

151

Nonetheless, the sheer extent of the split took most observers by surprise, and was for many years missed by a United States aroused by the fear of a global Communist conspiracy. Admittedly, the Korean War and the subsequent Chinese-American jockeying over Taiwan took attention from the lukewarm state of the Moscow-Peking axis, in which Stalin’s relatively small amounts of aid to China were always tendered for a price which emphasized Russia’s privileges in Mongolia and Manchuria. Although Mao was able to redress the balance in his 1954 negotiations with the Russians, his hostility to the United States over the offshore islands of Quemoy and Matsu and his more extreme adherence (at least at that time) to the belief in the inevitability of a clash with capitalism made him bitterly suspicious of Khrushchev’s early

détente

policies. From Moscow’s viewpoint, however, it seemed foolish in the late 1950s to provoke the Americans unnecessarily, especially when the latter had a clear nuclear advantage; it would also be a setback, diplomatically, to support China in its 1959 border clash with India, which was so important to Russia’s Third World policy; and it would be highly unwise, given the Chinese proclivity to independent action, to aid their nuclear program without getting some controls over it—all of these being regarded as successive betrayals by Mao. By 1959, Khrushchev had canceled the atomic agreement with Peking and was proffering India far larger loans than had ever been given to China. In the following year, the “split” became open for all to see at the World Communist Parties’ meeting in Moscow. By 1962–1963, things were worse still: Mao had denounced the Russians for giving in over Cuba, and then for signing the partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty with the United States and Britain; the Russians had by then cut off all aid to China and its ally Albania and increased supplies to India; and the first of the Sino-Soviet border clashes occurred (although never as serious as those of 1969). More significant still was the news that in 1964 the Chinese had exploded their first atomic bomb and were hard at work on delivery systems.

152

Strategically, this split was the single most important event since 1945. In September 1964,

Pravda

readers were shocked to see a report that Mao was not only claiming back the Asian territories which the Chinese Empire had lost to Russia in the nineteenth century, but also denouncing the USSR for its appropriations of the Kurile Islands, parts of Poland, East Prussia, and a section of Rumania. Russia, in Mao’s view, had to be reduced in size—in respect to China’s claims, by 1.5 million square kilometers!

153

How much the opinionated Chinese leader had been carried away by his own rhetoric it is hard to say, but there was no doubt that all this—together with the border clashes and the development of Chinese atomic weapons—was thoroughly alarming to the Kremlin. Indeed, it is likely that at least some of the buildup of the Russian armed forces in the 1960s was due to this perceived new

danger to the east as well as the need to respond to the Kennedy administration’s defense increases. “The number of Soviet divisions deployed along the Chinese frontier was increased from fifteen in 1967 to twenty-one in 1969 and thirty in 1970”—this latter jump being caused by the serious clash at Damansky (or Chenpao) island in March 1969. “By 1972 forty-four Soviet divisions stood guard along the 4,500-mile border with China (compared to thirty-one divisions in Eastern Europe), while a quarter of the Soviet air force had been deployed from west to east.”

154

With China now possessing a hydrogen bomb, there were hints that Moscow was considering a preemptive strike against the nuclear installation at Lop Nor—causing the United States to make its own contingency plans, since it felt that it could not allow Russia to obliterate China.

155

Washington had come a long way since its 1964 ponderings about joining the USSR in “preventative military action” to arrest China’s development as a nuclear power!

156