The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (77 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

The enormous surge in American defense expenditures for several years after 1950 clearly reflected the costs of the Korean War,

and

Washington’s belief that it needed to rearm in a threatening world; the post-1953 decline was Eisenhower’s attempt to control the “military-industrial complex” before it damaged both society and economy; the 1961–1962 increases reflected the Berlin Wall and Cuban missile crises; and the post-1965 jump in spending showed the increasing American commitment in Southeast Asia.

119

Although the Soviet figures are mere estimates and Moscow’s policy was shrouded in mystery, it is probably fair to deduce that its own 1950–1955 buildup was caused by worries that war with the West would lead to devastating aerial attacks upon the Russian homeland unless its numbers of aircraft and missiles were greatly augmented; the 1955–1957 reductions reflect Khrushchev’s

détente

diplomacy and efforts to release funds for consumer goods; and the very strong buildup after 1959–1960 reveals the worsening relations with the West, the humiliation over the Cuba crisis, and the determination to be strong in all services.

120

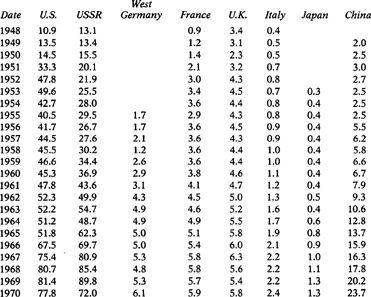

Communist China’s more modest buildup was as much a reflection of its own economic growth as of anything else, but the 1960s defense increases suggest that Peking was willing to pay the price for its break with Moscow. As for the western European states, the figures in

Table 37

show both Britain and France greatly increasing their defense expenditures at the time of the Korean War, and France’s expenditures still

rising until 1954 because of its embroilment in Indochina; but thereafter both those powers, and West Germany, Italy, and Japan in their turn, permitted only modest increases (and an occasional decline) in defense spending. Apart from China’s growth—and those figures also are very imprecise—the pattern of arms spending in the 1950s and 1960s still conveys the impression of a bipolar world.

Table 37. Defense Expenditures of the Powers, 1948-1970

118

(billions of dollars)

Perhaps more significant than figures alone was the multilevel and multisided character of the arms race. Although shocked by the Russian achievement of manufacturing its own A-bomb in 1949, the United States believed that it could inflict far more damage upon the USSR in a nuclear exchange than the USSR could inflict on it. On the other hand, as the strongly ideological NSC-68 (National Security Council Memorandum 68, of January 1950) put it, it was imperative “to increase as rapidly as possible our general air, ground and sea strength and that of our allies to a point where we are militarily not so heavily dependent on atomic weapons.”

121

Between 1950 and 1953, in fact, U.S. ground forces tripled in size, and although much of this was due to the calling-up of reserves to fight in Korea, there was also a determination to convert NATO from a set of general military obligations into an

on-the-ground

alliance—to forestall a Soviet overrunning of western Europe which both American and British planners feared likely at this time.

122

Although there was no real prospect of the fantastic total of ninety Allied divisions being created on the lines of the Lisbon Agreement of 1952, there was nonetheless a significant rise in military commitments to Europe—from one to five U.S. divisions by 1953, with Britain agreeing to station four divisions in Germany, so that a reasonable balance had been achieved by the mid-1950s, when the West German army was expanded to compensate for reductions made then by London and Paris. In addition, there were enormous increases in Allied expenditures upon their air forces, so that some 5,200 were available to NATO by 1953. While much less is known about the development of the Soviet army and air force in these years, it is clear that Zhukov was engaged upon significant reorganization once Stalin died—getting rid of masses of half-prepared troops, making units much more powerful, mobile, and compact, replacing artillery with missiles, and, in sum, giving them a much better capacity for offensive action than they had possessed in 1950–1951, when the West’s fear of attack was greatest. At the same time, it is clear that Russia, too, was placing the greatest proportion of these budgetary increases upon defensive and offensive air power.

123

A second and quite new area of the East-West arms race opened up at sea, although this was also in an irregular pattern. The U.S. Navy had finished the Pacific war trailing clouds of glory, because of the impressive performance of its fast-carrier task forces and its submarine fleet; and the Royal Navy also felt that it had had a “good war,” and one

much more decisively fought than the stalemated 1914–1918 conflict at sea.

124

But the coming of A-bombs (especially in the Bikini trials against a variety of warships) to be carried by long-range strategic bombers or missiles seemed to cast a cloud over the future of the traditional instruments of naval warfare and even over the aircraft carrier itself. In the post-1945 retrenchment of defense expenditures, and “rationalization” of the separate services into a unified defense ministry, both navies came under heavy pressure. They were rescued, at least to some extent, by the Korean War, which again saw amphibious landings, carrier-based air strikes, and the clever exploitation of western sea power. The U.S. Navy was also able to join the nuclear club with the creation of a new class of enormous carriers, possessing strike bombers equipped with atomic weapons, and, by the late 1950s, with the planned construction of nuclear-powered submarines capable of firing long-range ballistic missiles. The British, less able to afford modern carriers, nonetheless retained converted “commando” carriers for what were termed brushfire wars, and, like the French, also strove to create a submarine-based deterrent. If all western navies by 1965 contained fewer ships and men than in 1945, they certainly had a more powerful punch.

125

But the greatest stimulus to the continued expenditure of these navies was the buildup of the Soviet fleet. During the Second World War itself, the Russian navy had achieved very little, despite its large submarine force, and most of its personnel had fought on land (or assisted at river crossings by the army). After 1945, Stalin permitted the construction of many more submarines, based upon superior German designs and probably to be employed in an extended coastal-defense role; but he also favored the creation of a larger surface navy, including battleships and aircraft carriers. This ambitious scheme was swiftly halted by Khrushchev, who saw no purpose in building large, expensive warships in an age of nuclear missiles; in this his views were identical to those of many politicians and air marshals in the West. What probably shook that assumption was the repeated examples of the use of surface sea power by Russia’s most likely foes—the Anglo-French sea-based attack upon Suez in 1956, the landing of U.S. forces in Lebanon in 1958 (thus checking the Russian-backed Syrians), and especially the

cordon sanitaire

which American warships placed around Cuba in the tense confrontation of the missile crisis of 1962. The lesson which the Kremlin (urged on by the influential Admiral Gorschkov) drew from these incidents was that until Russia also possessed a powerful navy, it would continue to be at a serious disadvantage in the world-power stakes—a conclusion reinforced by the U.S. Navy’s rapid move to Polaris-missile-carrying submarines in the early 1960s. The result was both a massive expansion in virtually all classes of vessels in the Red Navy—cruisers, destroyers, submarines of all

types, hybrid aircraft-carriers—

and

a massive expansion in their deployment overseas, challenging western maritime predominance in, say, the Mediterranean or the Indian Ocean in a manner which Stalin had never attempted.

126

This form of challenge could, however, be regarded in traditional terms, as was clear by the many comparisons which observers made between Admiral Gorschkov’s buildup and Tirpitz’s four decades earlier; and even if the Soviet Union appeared committed to a new “naval race,” it would be decades (if at all) before it could match the massively expensive carrier task forces of the U.S. Navy. The really

revolutionary

aspect of the post-1945 arms race was occurring elsewhere, in the sphere of atomic weapons and long-range missiles to project them. Despite the horrific casualties caused at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there still remained many who saw in atomic weapons “just another bomb” rather than a watershed in the history of man’s capacity for destruction. Moreover, following the failure of the 1946 Baruch Plan to internationalize atomic-power developments, there was the comforting thought that the United States possessed a nuclear monopoly and that the Strategic Air Command’s bombers compensated for (and deterred) the large Soviet superiority in ground forces;

127

the western European states in particular accepted that a Russian military invasion would be answered by American (and later British) airborne bombings with nuclear weapons.

Technological innovations, and Soviet advances especially, changed all that. Russia’s successful explosion of an atomic device in 1949 (well before most western estimates had predicted) broke the American monopoly. More alarming still was the construction of long-range Russian bombers, especially of the Bison type, which by the mid-1950s not only were assumed to be capable of reaching the United States but also were (erroneously) supposed to exist in such large numbers that a “bomber gap” existed. While the resultant controversy signified both the difficulty of gaining hard evidence about Russian capabilities and the U.S. Air Force’s tendency to exaggerate,

128

it was in fact only to be a few more years before the era of American invulnerability was over. In 1949 Washington had agreed to the production of a new “super” bomb (the H-bomb), of staggeringly larger destructive capacity. This seemed once again to promise to the United States a decisive advantage, and the early to middle 1950s witnessed, both in Foster Dulles’s startling speeches and in the Air Force’s own plans, a commitment to “massive retaliation” upon Russia or China in the event of the next war.

129

While this doctrine itself produced considerable private unease within both the Truman and Eisenhower administrations—leading to the buildup of conventional forces and tactical (i.e., “battlefield”) nuclear weapons, as alternatives to unleashing Armageddon—the chief blow to that strategy came from the Russian side.

In 1953, Russia also tested an H-bomb, a mere nine months after the American test. Moreover, the Soviet government had devoted considerable resources to exploiting German wartime technology on rocketry. By 1955 the USSR was mass-producing a medium-range ballistic missile (the SS-3); by 1957 it had fired an intercontinental ballistic missile over a range of five thousand miles, using the same rocket engine which shot

Sputnik

, the earth’s first artificial satellite, into orbit in October of the same year.

Shocked by these Russian advances, and by the implication that both U.S. cities and U.S. bomber forces might be vulnerable to a sudden Soviet strike, Washington committed massive resources to its own intercontinental ballistic missiles in order to close what was predictably termed “the missile gap.”

130

But the nuclear arms race was not confined to such systems. From 1960 onward, each side was also swiftly developing the capacity to launch ballistic missiles from submarines; and by that time a whole variety of battlefield nuclear weapons, and shorter-range rockets, had been constructed. All this was attended by the intellectual wrestlings of both strategic planners and civilian analysts in their “think tanks” about how to manage the various stages of escalation in what was now a strategy of “flexible response.” However clear the solutions proposed, none of this managed to escape from the awful problem that it was going to be difficult if not impossible to integrate nuclear weapons into the traditional ways of fighting conventional warfare (it was soon realized, for example, that the battlefield “nukes” would blow up most of Germany). Yet if recourse were had to launching high-yield H-bombs upon Russian and American soil, the mutual casualties and damage would be unprecedented. Locked in what Churchill called a mutual balance of terror, and unable to

dis

invent their weapons of mass destruction, Washington and Moscow threw more and more resources into the technology of nuclear warfare.

131

And while both Britain and France were pushing ahead with their own atomic bombs and delivery systems in the 1950s, it still seemed—by all contemporary measure of aircraft, missiles, and nuclear bombs themselves—that in this field, too, only the superpowers counted.

The final major element in this rivalry was the creation by both Russia and the West of alliances across the globe, and the competition to find new partners—or at least to prevent Third World countries from joining the other side. In the early years, this was overwhelmingly an American activity, flowing from its advantageous position in 1945, from the fact that it already had many garrisons and air bases outside the western hemisphere, and from the equally important fact that so many countries were looking to Washington for economic and sometimes military support. By contrast, the USSR was desperately needing to rebuild itself, its chief foreign concern was the stabilization

of its own borders on terms favorable to Moscow, and it had neither the economic nor the military instruments of power to project itself farther afield. Despite territorial gains in the Baltic, northern Finland, and the Far East, Russia was still, relatively speaking, a landlocked superpower. Moreover, it now seems clear that Stalin’s view of the world outside was one overwhelmingly charged with caution and suspicion—toward the West, which, he feared, would not tolerate open Communist gains (e.g., in Greece in 1947); and also toward those Communist leaders, such as Tito and Mao, who were certainly not “Soviet puppets.”

132

The setting-up of the Cominform in 1947 and the strong propaganda about supporting revolutionaries abroad had echoes from the 1930s (and even more, from the 1918–1921 era); but in actual fact Moscow seems to have avoided foreign entanglements in this period.