The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards (27 page)

Read The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards Online

Authors: William J Broad

Tags: #Yoga, #Life Sciences, #Health & Fitness, #Science, #General

His sketch featured happy little stick men. The first stood, arms out, and the next frame showed it bent over sideways, hand to foot. The second sat upright on the floor with one leg stretched out and an arm reaching back in a spinal twist. The third lay flat and lifted the legs with a belt. The stick figures were informative but only rough outlines. Fishman said his usual method was to go over the details with patients.

Every Tuesday in the late afternoon, he held a yoga session at his Upper West Side office. He called it a three-ring circus and invited me to visit.

The office was slightly chaotic amid the transition from regular hours to yoga therapeutics. Patients came and went. A portly man hobbled around on crutches, his leg in a large cast. A young man sat on the floor, rubbing a bad ankle. “Undefeated in the Playoffs,” read the back of his bright red T-shirt. A big cardboard box overflowed with colorful yoga mats. The receptionist folded up a room divider and the area suddenly became large enough for a small class.

Patients drifted in, put down mats, and began stretching. Maybe six or seven showed up, from their twenties to their sixties. There were also two yoga teachers, both women. One was a regular assistant. The other had recently met Fishman at a meeting in Los Angeles on yoga therapy and wanted to observe him in action.

Fishman came in, bouncy and engaging, immediately the ringmaster. He chatted and led warm-ups, wearing bright yellow gym shorts and a gray muscle shirt. Nothing about him appeared to be sixty-six.

When the visiting teacher volunteered that she had recently had surgery for a bunion—the painful curvature and swelling of the big toe—he showed us a simple treatment. It consisted of stretching both toes toward each other and then back to their normal straightforward positions; back and forth, back and forth, stretched and relaxed.

Everyone tried it. He

said the exercise worked to strengthen a specific muscle, the abductor hallucis. On the sole of his own foot, he showed us its location and confidently predicted that pumping it for twenty to thirty seconds each day would prevent bunions and might reduce or undo them. Fishman said he developed the method four years ago after discovering a bunion forming on his own foot. It went away. He predicted that the yoga teacher would never need surgery on her other foot if she did the exercise. Fishman added that, for a study, he was tracking about twenty patients with bunions who regularly did the stretch. “It seems to be working,” he remarked.

Fishman divided the class into groups. In the smallest, his assistant worked with a petite woman who had multiple sclerosis. This degenerative disease of the central nervous system leaves its victims weak, numb, poorly coordinated, and prone to vision, speech, and bladder problems. Fishman wrote a book on the disease with Eric L. Small, a Los Angeles yogi who at the time of their collaboration had fought multiple sclerosis for more than a half century and had long found relief in yoga. Their recommended routine had nothing to do with fostering cures and everything to do with promoting a better quality of life—trying to reduce handicap and disability, increase safety, lessen fatigue, strengthen muscles, increase range of motion and coordination, improve balance, raise confidence, and promote inner calm.

Teacher and patient began the session in a standing position. The workout was warm, informal, and quite different from the traditional rounds of yoga postures.

The yogini, Rama Nina Patella, had the patient start by holding on to the top of a file cabinet and bending down, stretching her arms and back in a fashion similar to what would happen in Downward Facing Dog. It didn’t work. The left side of the patient’s body was beginning to atrophy, and her left hand had a hard time gripping the file cabinet. So Patella had her try again. Only this time the patient held onto Patella’s hips, and Patella clutched her arms. It worked. The patient was able to stretch down, long and slow. “Take your thighs back. Stretch this arm out as much as you can,” Patella said of the weakened side. “Keep breathing. Reach with this arm, the arm that’s kind of unwilling. Stretch that arm. That’s good.”

After a minute or two in that pose, the patient stood back up, beaming.

Mountain,

Tadasana

Patella had her do the Mountain

pose, or Tadasana. From the outside, the pose seems simple and inconsequential. The student just stands there. But done right, it actually involves the subtle rearrangement and realignment of the whole body from head to heels, with muscles tensing and pulling and unbending the bones, the neck straight, the shoulders broad, the breath relaxed.

“Press your feet into the floor and lift your chest,” Patella said. “You want a feeling in your feet like the roots of a tree growing into the earth and, from that rooted action, uplifting. Chest is open. Your shoulders are back. Let your breath flow as freely as possible. Good.”

The patient had her eyes closed, concentrating, lifting and stretching. Her usual list to the left was somewhat diminished. She smiled.

Elsewhere, the room pulsed. A man in the class had, like me, herniated the disk that lies between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae. Fishman had him doing a series of spinal extensions and elongations, and had the visiting yoga teacher shower him with attention.

As for himself, Fishman

worked with a group of three women who, he said, had various kinds of abdominal problems. One suffered from prolapse—a condition where the uterus falls out of place, descending from the pelvis into the vagina. Normally, the muscles and ligaments of the pelvic floor hold the uterus in place. Uterine prolapse occurs when the muscles and ligaments weaken and stretch, undoing the usual support. Treatments include surgery, exercise, lifestyle changes, and a device worn inside the vagina that props up the uterus. Fishman took a direct approach that addressed the roots of the problem by seeking to strengthen core muscles and abdominal support.

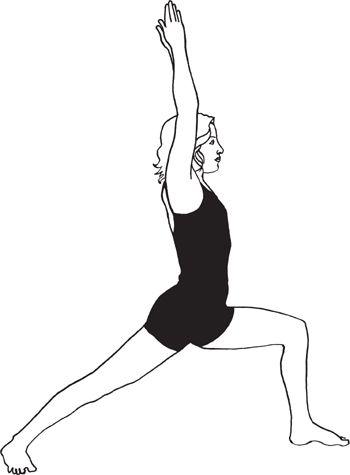

He showed the women how to do a variation of the Warrior pose, or Virabhadrasana. From a standing position, he moved one foot forward and the other back, raised his arms straight up, and bent his forward knee. The result was the slow lowering of his pelvis as well as the stretching of his legs and abdomen. “Then you come down,” Fishman said, dropping the thigh so low that it formed a right angle with the back. “Like this.” He stretched his arms high up and his pelvis down low. Then the women tried.

Warrior,

Virabhadrasana

Fishman moved among them, offering words of advice, encouragement, and—sparingly—praise. He exuded confidence and encouraged them to try hard. “Stretch up as high as you can,” he urged, “stretching way up, way up. Good.”

After a pause, Fishman led the women into another Warrior variant. It required not only stretching but balance. From the first pose, he had them stand on one leg while raising the rear leg to a horizontal position and lowering the arms and torso. It was like Superman flying with one leg extended straight down. Fishman moved among the women, offering alignment tips. “Bring this hip down,” he told one woman, lightly touching the hip. She quickly rotated her hips into a horizontal plane.

“Good. With the hip down, raise the leg up.” He put his hand under her leg, signaling how he wanted her to raise it, and she gave a little moan at the effort. “See what you’re doing?” he asked. “You’re stretching everything in here”—he motioned to her lower torso—“front and back.”

And so it went. For the better part of an hour, Fishman led the women through numerous sitting and standing poses, all aimed at stretching and strengthening their midregions. “Try to engage those muscles,” he said at one point, encouraging the women to push themselves even while paying attention to the sensations.

Fishman closed with a meditation. It began with a few minutes of relaxed breathing with eyes shut to foster inner awareness of body position and sensation, especially in the lungs.

“Feel on the right side and the left side,” he said. “Is it the same? Feel your shirt against your skin. Is it pushing equally? How about the tenor of your breathing? Are you a soprano or an alto or a baritone? Listen to your breathing. Don’t try to do anything. Just pay attention. How does the air go in? Both nostrils? One? Feel the bottom of your lungs, the sides, the back and front. Feel what’s going on in there—these capricious things that we need so desperately and never see.”

Then there was quiet.

Weeks later, I returned to Fishman’s Upper East Side office to ask some follow-up questions. He said his staff was dismantling his West Side office for a bigger space around Columbus Circle. It would have a larger room for classes, Fishman said. The yoga aspect of his practice was clearly expanding.

He said none of

the other doctors in his practice did yoga or prescribed it to patients. It was his specialty alone, though, he added, one of his aides and a physical therapist also studied the discipline.

I asked how, overall, yoga had aided his practice. He said it acted as a kind of laboratory for the nurturing of physical creativity, letting him experiment on his own body and that of willing patients to discover new kinds of natural cures and therapies. Without yoga, he said, “I’d lack the most interesting, least expensive, and most helpful and versatile form of treatment that I have.”

I asked if he had ever had surgery on his left rotator cuff. No, he answered. The yoga solution, he added, had been working just fine for seven years now.

He held his left arm high over his head and smiled.

To become a physician, Fishman had to undergo an ordeal of schooling and formal assessment that, in the end, gave him admission to an elite club. The first big evaluation was the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination, a series of tests taken during medical school and residency. He then earned a medical license from the State of New York and its board of medical examiners. To stay in good standing, his license required that he do fifty hours of continuing education each year. He also earned professional certifications from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, the New York State Workers’ Compensation Board, and such professional bodies as the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

So, too, the physical therapists who work for Fishman are licensed through the state and the American Physical Therapy Association. These organizations require graduate degrees in physical therapy, as well as continuing education. At first the degree tended to be a master’s, but the field of late has moved rapidly toward requiring a doctorate. The course work for such a diploma is heavy in embryology and histology, anatomy and physiology, pathology and pharmacology, kinesthesiology and imaging techniques. Many states require the dissection of cadavers.

The goal of mandatory licensure is to form groups whose members have met certain minimal requirements that—among other things—are meant to protect the public from harm. The highly regulated world of medicine is typically backed by the force of law and seeks to deter and penalize interlopers. In New

York State, where I live, practicing medicine without a license is a felony punishable by up to four years in prison.

What Fishman underwent to become a yoga therapist bears no resemblance. He received no formal training, earned no license, faces no requirements for continuing education, and will never confront any oversight panel or threat of reprimand and penalization. His complete freedom of activity arises not because of any deficiency on his part but because the United States has no regulatory body for yoga therapy. None. Zip. Nada. Few countries do. The field is, on the whole, completely unlicensed and unregulated.

Even so, the yoga community has managed to foster the illusion that the United States has a system in place for the accreditation of yoga therapists. That New Age fiction is helping to promote the field’s growth. Unfortunately, it is also deceiving people, some desperate for healing because of serious illnesses and injuries.

Yoga teachers who aspire to the role of contemporary healer often put after their names the initials RYT—short for Registered Yoga Therapist. They do it on books, brochures, and Internet sites. The practice may seem innocuously similar to how physicians use MD and dentists DDS. But the situation is entirely different.