The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards (30 page)

Read The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards Online

Authors: William J Broad

Tags: #Yoga, #Life Sciences, #Health & Fitness, #Science, #General

I proceeded to discover

that modern yoga throbs with open sexuality ranging from the blatantly erotic and the bizarrely kinky to the deeply spiritual. The veil hung ever so carefully by the early gurus and the Hindu nationalists has fallen away.

Routinely, yoga now promises to transport any serious practitioner into realms of sexual bliss that go far beyond the hot, moaning, knee-knocking variety of the bedroom. The trend is highly commercial in nature and has produced many thousands of books, websites, how-to articles, and video discs.

Better Sex Through Yoga

—a set of three DVDs (beginner, intermediate, and advanced)—promises to reward the student with “intense, long-lasting, full-body orgasms.” How long? The woman teacher gives no particulars. But scantily clad and smiling coyly, she promises to take “you harder, deeper, and further than you’ve been in your workout—and your sex life.”

After exploring this world for a while, the big picture suddenly came into view. I saw how limited science had obscured key evidence, why yoga reverberated with so many scandals, and how the discipline itself began as a sex cult. The pieces of the puzzle, as they say, fell into place.

One revelation centered on sexual misconduct among some of the world’s most celebrated gurus. I learned of philanderers who acted with impunity and female victims who tended to rationalize the sex as some kind of spiritual test or ritual initiation. Most had a difficult time finding fault with men they saw as virtual gods.

Happily, my research also showed that the women began to resist and even take legal action. In 1991, protestors waving placards (“Stop the Abuse,” “End the Cover Up”) marched outside a Virginia hotel where Swami Satchidananda (1914–2002)—a superstar of yoga with long hair and a full beard who gave the invocation at Woodstock—was addressing a symposium. “How can you call yourself a spiritual instructor,” a former devotee shouted from the audience, “when you have molested me and other women?”

Another case involved Swami Rama (1925–1996), the man who impressed scientists by seizing control of his palm temperature. In 1994, one of his victims filed a lawsuit charging that he had initiated the abuse at his Pennsylvania ashram when she was nineteen. He evaded deposition. Ultimately, he traveled to India, leaving behind his ashram in the Pocono foothills and its four hundred rolling acres. The case moved ahead despite his absence. In 1997, shortly

after his death, a Pennsylvania jury awarded the young woman nearly $2 million in compensatory and punitive damages.

Even Kripalu came under fire. Former devotees at the Berkshires ashram won more than $2.5 million after its longtime guru—a man who gave impassioned talks on the spiritual value of chastity—confessed to multiple affairs.

I came to see these episodes as windows into the unruly forces at work in some of yoga’s most developed bodies. The fallen seemed to confirm Iyengar’s point about the crossroads of destiny. For science, the cases suggested that vigorous practice could stir the hormones and passions to such an extent that even pious men of high ambition could lose their way. The misadventures also offered a bittersweet tribute to yoga revitalization. It turned out that a surprising number of the philandering gurus were in their sixties and seventies.

My take on the subject kept getting reinforced as new episodes broke into public view—at times with a colorful new spin. Bikram Choudhury, the hot entrepreneur, a man known for libidinal energy and a love of hyperbole, was asked about rumors of having sex with students. The sixty-four-year-old guru offered no denials but claimed he was blackmailed. “Only when they give me no choice!” he exclaimed. “If they say to me, ‘Boss, you must fuck me or I will kill myself,’ then I do it! Think if I don’t! The karma!”

With new resolve, I dug deep and uncovered a small trove of illuminating reports and investigations. They showed that yoga can in fact result in surges of sex hormones and brain waves, among other signs of sexual arousal. The newest studies add the weight of clinical evidence. Medical scans indicate that advanced yogis can shut their eyes and light up their brains in states of ecstasy indistinguishable from those of sexual climax. Meanwhile, new practitioners report that yoga improves their sex lives. The men and women say the benefits include better arousal, satisfaction, and emotional closeness with partners.

Little of this information is known publicly, despite yoga’s reembrace of Tantra and the erotic. Most is lost in the labyrinth of modern science.

I have come to see the lack of understanding as not only a disciplinary weakness but something of a missed opportunity. Yoga practitioners may know from personal experience that the discipline can act as a potent aphrodisiac and revitalize their sex lives. But the professions of medicine, health care, and psychological

counseling know little or nothing of such benefits despite their tireless promotion of costly treatments for low libido, arousal disorder, and sexual frustration. The same holds true of popular health guides.

As a result, sex authorities seldom if ever mention a holistic therapy that is quite natural and—as Fishman put it—free.

The ignorance goes right to the top. When Abraham Morgentaler wrote his 2008 book,

Testosterone for Life: Recharge Your Vitality, Sex Drive, Muscle Mass & Overall Health!,

the Harvard professor talked mainly of gels, creams, patches, injections, and pellets—all of which require prescriptions. His book made no mention of yoga, like most guides to hormone therapy.

The global pharmaceutical complex thrives on sex treatments, with sales booming in recent years. The marketing push is known derisively as Orgasm, Inc., and critics question whether it puts corporate profits above personal health.

It turns out that science over the decades has slowly uncovered an alternative that draws on the body’s own hidden resources. It has no advertisements, no sales force, no hustle, no giveaways for doctors, and no questions about pressure to take unnecessary and possibly unsafe drugs. If nothing else, it seems worth investigating.

Katil Udupa was an ambitious physician at the Benares Hindu University, his professional life a blur of activity on the school’s sprawling campus outside the holy city on the Ganges. He was, in many respects, a successor to Paul—a man of Western medicine who became deeply interested in the healing arts of India. He also exhibited some of Gune’s passion for institution building. In 1971, Udupa founded the school’s Institute of Medical Sciences.

He then proceeded to fall apart. After years of administration and its predictable crises, his outgoing nature started to crumble and Udupa ended up with a variety of nervous ills— chest pains, irritability, diffuse apprehension, emotional instability, and a sense of constant fatigue. The formal diagnosis was cardiac neurosis. We would call it burnout. Whatever the name, he was a nervous wreck.

Udupa took up yoga and found quick relief that slowly developed into a deep sense

of personal renewal. Intrigued, he began to study the medical literature about yoga and to investigate its potential for treating patients—especially those with chronic diseases that appeared to be linked to the kind of stresses and illnesses that he himself had experienced. His studies showed that yoga could dramatically improve a patient’s hormone profile, lowering, for instance, the high levels of adrenaline and other fight-or-flight hormones released in response to stress.

The body always puts survival ahead of pleasure. A corollary of that principle is that stress can smother the flames of desire, and relaxation can create a situation where smoldering embers get fanned into a blaze.

Udupa wondered if that kind of relationship held true on the biochemical level as well and, specifically, whether the reductions he was seeing in stress hormones meant that the body’s sex hormones were tending to increase. It was a smart question.

He and his colleagues studied a dozen young men. Their average age was twenty-three, about half of them single, and half married. The volunteers underwent yoga training for six months. The lessons started out easy and, month by month, grew harder. The first month included the Cobra, the Spinal Twist, the Wheel, and the Full Lotus.

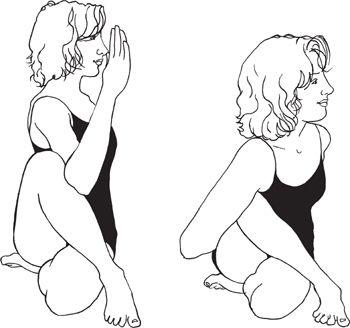

Spinal Twist,

Ardha Matsyendrasana

New poses added over

the months included the Plow, the Locust, the Bow, the Shoulder Stand, and the Headstand. The pranayamas included Bhastrika and Ujjayi, or Victorious Breath. Overall, by modern standards, the training was fairly rigorous.

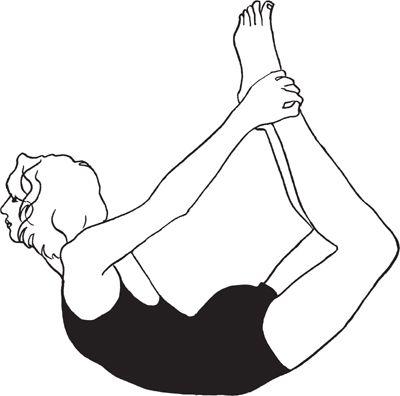

The scientists took urine samples from the young men at the start of the program and its conclusion. They found that the urinary excretion of testosterone rose significantly, its levels in some of the married men more than doubling. On average, the levels rose 57 percent. The results, the scientists wrote in 1974, suggested that yoga could prompt a “revitalization of the endocrine glands.” As for the mechanism, they speculated that yoga had improved the microcirculation of the blood through the men’s organs. In males, testosterone is made primarily in the testes but also to a lesser extent in the adrenal glands. It seems that poses such as the Bow, which exerts pressure on the genital region, might well serve as a stimulus to improved circulation.

Bow,

Dhanurasana

In 1978, Udupa published a summary of the hormone findings in his book

Stress and Its Management by Yoga.

He noted the clinical evidence of the testosterone rise and attributed it to “considerable improvement in the endocrine function of the testes.”

His hunch had proved correct. But Udupa made little of it. His finding was a particle of basic science in a blizzard of global research.

Living peacefully on the

Ganges a couple of hundred miles downstream from Benares and Udupa were advanced yogis who displayed a strong interest in science, their guru having named their ashram the Bihar School, after its location in Bihar state. It turns out they were interested in learning as well as teaching. A swami writing in

Yoga Magazine

, published by the school, called attention to Udupa’s testosterone finding. His brief reference was buried in an overview of Udupa’s yoga research. Still, the author, steeped in British English, noted how the hormone discovery suggested that yoga postures could improve “vitality and sexual vigour.”

His appraisal was clear-eyed but rare. For the most part, science as well as popular and yogic literature ignored the finding. The Bihar yogis noted the testosterone rise in 1979, shortly after the publication of Udupa’s book. It seems plausible that the finding caught their attention not only because of their proximity to the research but because their own experiences had convinced them of its physiological truth.

If science ignored the finding, investigators nonetheless threw themselves into acquiring a better understanding of testosterone. In Udupa’s day, the potent hormone was seen mainly as the force behind the male sex drive. Scientists knew that its levels fell with age, and that rises could lead to revitalization.

But over the years, modern biology found many other ways in which the little molecule can influence behavior and sexuality—doing so in both males and females. Not the least significant, studies showed that it acts to improve mood and a person’s sense of well-being. It seems likely that the hormone forms a significant part of yoga’s cocktail of feel-good chemicals.

Importantly, testosterone was shown to bolster attention, memory, and the ability to visualize spatial tasks and relationships. It sharpened the mind.

Surprisingly, testosterone also turned out to play an important role in female arousal. While adult males tend to produce ten times more testosterone than females, scientists found that women are quite sensitive to low concentrations of the hormone. They make it in their ovaries and adrenals, and its production peaks around the time of ovulation—a phase of the reproductive cycle associated with increased sexual activity. A number of studies have linked testosterone rises in women to enhanced desire, erotic activity, intimate

daring, and sexual gratification. The pharmaceutical industry is closely studying the hormone in hopes of finding a blockbuster drug like Viagra that it can sell to women.