The Secret Life of Uri Geller (10 page)

Read The Secret Life of Uri Geller Online

Authors: Jonathan Margolis

Tags: #The Secret Life of Uri Geller: Cia Masterspy?

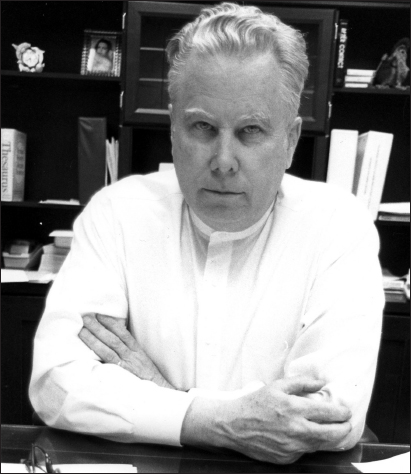

Colonel John Alexander, who taught spoon bending to US army officers.

Some of these experiments on using psychics to affect electronics were conducted as part of the Army’s Stargate project, according to Paul Smith, a captain – and remote viewer – on the team at Fort Meade. ‘There is some evidence that a certain kind of remote influence does work,’ he told BBC TV director Vikram Jayanti in his documentary,

The Secret Life of Uri Geller

. ‘That would, for example, be – well, the things that Uri Geller did – bending spoons, getting clocks to run, that kind of stuff. That’s a form of remote influence. And the PEAR Lab, Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research Laboratory, that ran for 27 years at Princeton University, has very strong evidence of people being able to influence the internal operations of a computer.’

One method Alexander used in the 1970s and 80s to proselytize on for psychokinesis as a military tool was something called a ‘PK party’. This concept had been invented by an introverted Boeing aeronautical and astronautical engineer called Jack Houck, who died in 2013. Houck developed a theory that metal bending was a metaphor for the power of the mind to do everything from maximizing creativity, to self-curing disease, to extracting rusty bolts from machinery. And he was convinced that anyone’s mind could be trained truly to interact with molecules of material.

Houck became interested in Puthoff and Targ’s remote-viewing programme, read all their papers, and began to do his own research into the subject. One aspect of it in particular, which he found out about through military contacts, fascinated him especially. This was the highly secret ‘precognitive’ remote viewing – the strange glimpses of the future (and, sometimes, the past, too) – that remote viewers like Geller and others seemed to display.

Houck began doing his own work, in parallel with Targ and Puthoff, with their cooperation. In one experiment he ran, a remote viewer described a randomly selected set of coordinates in the Caribbean, but with the alarming detail of a harrowing shipwreck, in which he sensed dozens of people dying. Houck discovered that such a passenger boat accident had indeed happened at this spot, but nine years earlier.

He developed a theory that certain ‘peak emotional events’ (PEEs) could transcend the boundaries of the known dimensions, that, as he puts in it his own engineering terms, ‘If you add an emotional vector to the space/time vectors, you have the start of the way things work.’ As an extension of that idea, he wondered whether you could actually create a paranormal event by inducing a highly emotional state – a PEE – in someone.

Houck discussed this idea at the various university parapsychology departments where his gathering new interest was taking him, and over time devised the PK party. Working with a metallurgist he was friendly with at work, he invited 21 people for a Monday evening event at his house. About half were proven remote viewers, half simply friends from his tennis club, all asked to take part in an unspecified experiment.

The surprised guests were each given either a fork or a spoon and told they were going to learn to bend them like Uri Geller simply by relaxing and having fun. It seemed a ridiculous idea, but its very silliness seemed to do the trick and the guests, who mostly knew one another, were all soon chatting and laughing as Houck had hoped they would. The metallurgist then gave them some instructions: they were all to ‘get a point of concentration in their head’, make it very intense and focused, and then ‘grab it and bring it down through your neck, down through your shoulder, through your arm, through your hand, and put it into the silverware at the point you intend to bend it.’ Then they were to command it to bend, release the command … ‘and let it happen.’

For a while, there was nothing. Then a 14-year-old boy, in full view of the circle of guests, had the head of his fork flop down by itself. Having seen this, almost everyone experienced, as Houck puts it, ‘an immediate belief-system change’, and within minutes, cutlery was softening and flopping over in 19 out of the 21 guests’ hands. The plasticity of the forks and spoons seemed to exceed anything in Geller’s experience. People were tying knots in the tines of the forks, and rolling up spoon bowls as if they were leaves.

Some of the cutlery bent at Jack Houck’s PK parties.

By the time he died, at the 360 parties for 17,000 people that Houck hosted, spontaneous bending was a common phenomenon. Seven- and eight-year-old children were among those bending tableware. So much cutlery was bent at Houck’s parties that guests often didn’t take it all home. Houck had suitcases full of grotesquely distorted spoons and forks that he could not bring himself to throw out.

As an engineer, Houck naturally tried to work out what was happening. He developed a theory that the energy that the mind somehow manages to ‘dump’ into dislocations and flaws that occur naturally in metal when it is forged softens it as surely as if I were heated to 425° Celsius. He even documented cases where metal was missing from spoons after they had bent. He said that although his thinking on the phenomenon was influenced by quantum theory to some extent, he was more inclined to look for straightforward engineering solutions. ‘The only thing I don’t know is how the mind dumps this energy into the dislocations. After that, it’s just engineering.’

Reflecting the military’s gathering interest in teaching regular, ‘non-psychic’ people to manifest PK ability as well as telepathy, John Alexander took the PK-party concept from California, where Houck lived and held most of his parties, to the centre of power, Washington DC.

‘The reason for teaching spoon bending,’ Alexander explains, ‘was to show people that things could happen that they did not expect, and to emphasize the importance of that, particularly from an intelligence standpoint. It was important that they ensure that when they looked at unusual data of any kind, that they [the CIA] did not dismiss it just because they thought it couldn’t be true. The overall problem with the professionally sceptical class of people is that they are very scared. If

psi

is true, their world view is incorrect.’

Today, ‘disruptive technologies’ are considered a good, progressive thing, but at a time when the pace of technological change was more sedate than now, this new science did not attract an enthusiastic following. ‘I worked with an Army engineer once on a

psi

-related project,’ says Alexander, ‘and he actually came out and said, “Don’t tell me something that says I have to relearn physics, because I do not want to hear it.” But most of the sceptics are not that honest. They won’t say, “I don’t want to hear it.” They will just say it’s not true, therefore it isn’t. When all else fails, ignore the facts. Data that doesn’t fit is categorically rejected.

‘We stressed to folks,’ Alexander continues, ‘that bending silverware is of very limited practical value. You can make mobiles and things like that, but as far as something to do, it doesn’t make a lot of sense. What we did suggest was that it certainly impacts belief systems, and also that they could take and use similar kinds of energy for things like healing and other practical applications.’

How high up the Washington tree did word of the PK party spread? ‘Well,’ Alexander says, ‘I had the Deputy Director of the CIA at my house in Springfield, Virginia, for a PK party. But compared to potential war with the Soviet Union, it was noise, so, no, we didn’t have the President there.’

The most dramatic party Alexander ran was at a military camp for a senior group of US army commanders working in intelligence at various locations around the world, who had flown in for their regular quarterly meeting. ‘We were using the Xerox training centre outside Washington DC,’ he recounts. ‘We had a session and there was a commotion over in one area. This guy, who was a science adviser at a civilian equivalent of a two-and-a-half-star general, turned his head, and his fork dropped a full 90 degrees.’

‘I didn’t see it, but the guy next to him did, and screamed, “Did you see that?” I said I suspected a trick, because there were a lot of people there who would have liked to see me fail, and I was waiting for them to say, “Ha ha! We did it. You don’t know what you’re looking at.” So I was cautious. But by now, people were watching. And while we were all watching, the fork went back up, back down again, and finally went about half way and stopped. This is with all the generals and colonels watching, and the guy just put it down and said, “I wish that hadn’t happened.” It scared the crap out of him. Fortunately, we were sequestered, which means it was an isolated, live-in conference, and we had a shrink with us. But it took us a couple of days to put the guy together. His belief system was not prepared. He was based in Europe, so he went back to his station OK. What he did tell someone later was that he tried it once again at home by himself and it happened again, but by now, he was able to deal with it.’

These dramatic, challenging events – all of which, it must be remembered, were sparked off by Uri Geller being discovered in Israel and, later, arriving in the USA – were happening at the same frenetic time that the bizarre scenario at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory in California, as outlined in

Chapter 2

, was unfolding. In the same period, Uri experienced something else which made him want to give up on laboratory work and concentrate, for the while at least, on his ever-burgeoning show business career.

He recounts being spirited off to a government installation where he was asked to do something quite bizarre. He refuses point-blank to say in which country this installation was – a refusal that perhaps indicates it might have been Israel, or possibly a US facility in Mexico – but is insistent that it was not a CIA operation. ‘They took me to a laboratory. In this laboratory, which was a white room with no windows – maybe there was a chair and a table – and there stood a pig, a big pig. The scientist looks at me and says, “Okay, Uri, we’re going to go out for lunch. Stay here with the pig and stop his heart.”

Having been apparently suborned into this role as a kind of voodoo, psychic assassin was the last straw for Uri. ‘I just could not believe what I was hearing. Of course it was a pig, because a pig has a very similar heart to a human being. I was just so stunned. I had become a vegetarian many years before, and I love animals. And I was shattered, actually, by this request. It was like everything toppled down on me. It felt like it was the destruction of everything I’d done so far.’

A feeling that the ultimate target of the programme was Yuri Andropov, the long-time head of the KGB and who later became the Russian leader for a brief period, gripped Uri and grew in intensity. ‘They were asking me to see if the power of the human mind could stop the human heart. I went into the room and talked to one of the scientists and said I wasn’t interested in this at all, because it isn’t in my nature to do such a thing. I was very quiet and very shocked. I asked to leave and they drove us – because this was a base outside a certain city – back to the hotel, and then I just flew back to New York.’

I SPY

S

o if assassinating pigs (or goats, as in the partly fictionalized George Clooney film) by the power of thought was off limits for him, what specifically, do we know Uri Geller did do as a spy in the years after his nonspecified intelligence work back in Israel?

Eldon Byrd believed that in the run-up to his arrival in the USA at the end of 1972, Uri was asked by the Israelis to go to Munich, where the Olympic Games were to be held. ‘I didn’t know him then,’ Byrd said, ‘but he once mentioned to me that he was in Munich at the request of a particular person in the Mossad and had told them after sensing out the site before the Games not to send the Olympic team over and they did anyway.’ On 5 September, ten days into the Games, a group of Palestinian terrorists, reportedly with the connivance of a few sympathetic German neo-Nazis, broke into the Olympic Village and went on to murder 11 Israeli athletes and a West German policeman. According to Byrd, Uri was ‘really pissed off about that and he was saying he didn’t want to work with them any more.’

In late 1975, two New York friends of Uri’s, the concert pianist Byron Janis and his wife Maria, recall Ariel Sharon, then a retired major general working as a special aide to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, meeting with Uri at their Park Avenue apartment and having lengthy discussions about Israeli matters. ‘They were obviously prepping him for something,’ Janis says.