The Secret Life of Uri Geller (7 page)

Read The Secret Life of Uri Geller Online

Authors: Jonathan Margolis

Tags: #The Secret Life of Uri Geller: Cia Masterspy?

So how did the three scientists confronted with this event in the motel room in Livermore react immediately after it happened? ‘Our discussion was a little more mundane after the event than you might expect,’ says Green, ‘because we had been working together for a long time and regarding the matter of paranormal activity existing, well, we were already beyond that. We had already gotten to the point that scientists do where you make an observation in the laboratory that you don’t understand and you know you’ve got to collect more data, but you know it’s not magic and it’s not a gremlin. You don’t know what it is, and in the case of this kind of work it was an extension of a sort of paranormal landscape, none of which we really understood at that time. We understand it better today, but we still don’t understand most of it.

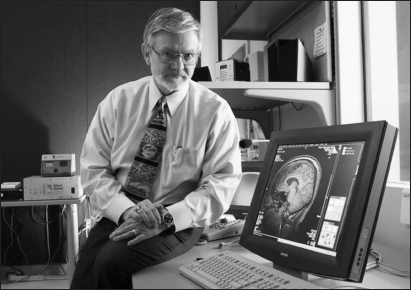

Dr. Kit Green, former CIA Assistant National Intelligence Officer.

‘So we knew we didn’t have a physics that would explain what we were seeing, both at Livermore and SRI and the motel room, and dozens of other circumstances in which absolutely clearly odd but veridical – that’s to say is very true – data was being acquired which showed that Uri and other individuals were producing information that could only otherwise be obtained by satellites. There was nothing that could be tampered with, so there was no concern in our minds that this was a magic show.

‘Where there was concern in our minds was, what did we think the chances were that somebody had a listening device in our room – that someone was running an operation to test our gullibility? We discussed not whether it was a magic trick, but was it a national entity of some sort was doing this. We talked extensively about how somebody – yes, maybe the KGB – could have arranged to have someone listening, and at the moment when I was asking about the severed arm scenario, bang on the door and do something that would fit the story I was telling.

‘It takes some believing that it was the KGB. And I didn’t really worry that it was the United States government doing it because they knew by then, after a number of years, that the phenomenology was absolutely real because we were testing it in circumstances where the controls were architected to be absolutely foolproof. And the events couldn’t possibly be magician controlled because it was orders of magnitude more complicated than magicians could achieve. So we knew the government knew this was real, so it wasn’t our government trying to destabilize us.’

The strange Livermore events are unique in the Uri Geller story in that they are the only instance to be found of anything that might be described as a dark happening around him, the stuff indeed of witchdoctors, black magic and nightmares. Nowhere else is there a report, however fanciful, of such things happening, let alone a group of nuclear scientists becoming unhinged because of seemingly paranormal experiences. Uri and other serious people who know him well have pondered over the years on whether his subconscious, objected to him working with men whose job was researching and developing nuclear warheads. It seems odd that something so frightening to others would happen just this once, when he happened to be working with people who helped create weapons capable of wiping out most of the world.

‘The effect on the scientists was life changing, so it seems. To my knowledge, they all, or most of them, resigned,’ says Kit Green. ‘I don’t know the details, but the information I had was that they quit from Livermore. The reason I had been meeting with them, after all, was that they wanted to quit.’

* * *

Uri’s life as the subject of scientific experimentation in the early 1970s continued in so many laboratories that he sometimes struggles to remember which was which. The weirdness that surrounded him wherever he went continued too; the very profusion of strange events affecting hundreds of people would suggest that, were he a uniquely talented trickster, he would still, as Kit Green argues, have needed the backroom staff of 50 David Copperfields (or half the KGB’s manpower) to arrange for dazzling, puzzling, seemingly inexplicable and inexorable happenings to shoot off in their hundreds and thousands like a years-long fireworks display.

When, some while after the SRI programme ended, the US Army centralized all the psychic research being done around the country into one overarching military psychic project based at Fort George G. Meade US Army post in Maryland, home of the National Security Agency and the Defense Information Systems Agency, Uri was not on the psychics roster for some reason.

Could this be because he was seen as having powers greater than other high-quality psychics such as former police commissioner, Pat Price, and was part of a greater plan altogether? Was it because Uri was becoming paranoid that the Russians, the Arabs, or even his patrons at the CIA would attempt to assassinate him? Was it because, as Puthoff and Targ now maintain, spectacular and baffling though his abilities were, in terms of reliability he wasn’t actually the best of the psychics the US government had to hand? Was it because his devotion to the American cause was diluted by his loyalty to Israel? The two countries are longstanding allies, but this doesn’t mean Israeli intelligence doesn’t spy on the USA and the USA on Israel; this is the way of the real world.

In terms of loyalty to US interests, Uri had to be regarded by anyone sensible as a young, green, very slightly loose cannon at the very least; apart from anything else, he was still a foreign national, living in the USA on a visa. Or was Uri’s withdrawal from lab experimentation simply a matter of a young, handsome, single man being bored and wanting to get on with being, as one of his best American friends of the time puts it, ‘a freakin’ rock star’?

Dr David Morehouse, a career army man recruited into the Fort Meade programme as a remote viewer, but who was also given the privilege of overviewing the programme to a certain extent, maintains that Uri was the most remarkable of the psychics available.

‘I came to know of Uri when I was in the remote-viewing unit because one of the first things you were required to do was go through the historical files, and in these files were constant references to Uri and Uri’s early involvement at Stanford Research Institute,’ Morehouse says. ‘It was very clear in all of the historical documentation, the briefs that were passed on to the intelligence community, that Uri Geller was without equal. None of the others came even close to Uri’s abilities in all of the tests.

‘What interested me was that this was not a phenomenon that was born in some back room behind a beaded curtain by a starry-eyed guy; this was something that was born in a bed of science at Stanford Research Institute, being paid for heavily by the CIA. And also, these were two laser physicists, not psychologists, but hard scientists brought in to establish the validity and credibility, to see if it works as an intelligence collection asset, and if it works, to develop training templates that allow us to select certain individuals that meet a certain psychological profile, and establish units that can gather and collect data using certain phenomenon. And their answer to all those things was ‘Yes’. If Targ and Puthoff had said, “Well, yes, there is a little something to it, but we can’t explain it, it’s not consistent and isn’t of any value,” well fine, but obviously it met all the criteria and 20-odd years later, they were still using it.’

But the testing took its toll on Uri. When celebrities are interviewed by the media, they often get frustrated at being asked the same questions a thousand times, and wonder why each journalist feels the need to start every interview with, ‘So when were you born?’ or something equally basic. Scientists are similar; each programme of experimentation started from the very beginning, with the boring basics – boring at least to those who have been through the process many times.

When you think that Uri was probably unique in the whole history of celebrity in that he was simultaneously going through the chat-show interview mill

and

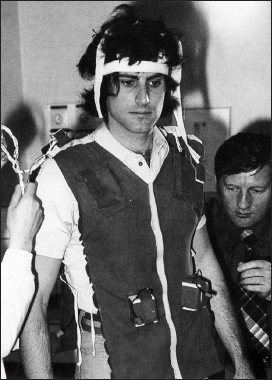

intensive and repetitive scientific investigation, it is a wonder he didn’t crack up. The amount of time he spent wired up in laboratories in the early 1970s is astonishing. On top of SRI’s work and that of Eldon Byrd, something we will read more of in the next chapter, he was investigated formally by several more laboratories, and did countless informal demonstrations to interested scientists.

In the United States, Uri did laboratory work with Dr Franklin at Kent State University – research that led to Franklin’s report,

Fracture surface physics indicating teleneural interaction

. He also worked with Dr Thelma Moss of the Neuropsychiatric Institute at UCLA’s Center for the Health Sciences, Dr Coohill at Western Kentucky University, and with William E. Cox at The Institute of Parapsychology at Durham, North Carolina. In Europe, he underwent testing at Birkbeck College and King’s College, both parts of London University, and at France’s INSERM Telemetry Laboratories, part of the Foch Hospital in Suresnes. In South Africa, he was examined by Dr E. Alan Price, a medical doctor and Research Project Director for the South African Institute for Parapsychology, who painstakingly documented over 100 cases of Geller’s effect on members of the public and university staffs as he travelled across South Africa on a lecture tour.

The reaction of scientists who met him informally, meanwhile, was almost routinely startling. The MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) professor Victor Weisskopf, who had worked with the quantum pioneers Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, Wolfgang Pauli and Niels Bohr, and was on the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb, said, ‘I was shocked and amazed [at] how Mr Geller bent my office key at MIT while I was holding it. The sturdy key kept bending in my hand. I cannot explain this phenomenon. I can only assume that it could relate to quantum chromodynamics’ [a specialized area of quantum related to String Theory].

Professor George Pake, a member of the president’s Science Advisory Committee and creator of Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Centre (Parc) said, ‘During our conversation, he demonstrated his mind-reading techniques and plucked out of my mind an image I was thinking of. It was very impressive.’

Over in the UK, the prominent Oxford neuropsychiatrist, Dr Peter Fenwick, spoke at length about Uri. ‘I was able to watch him bend a spoon on a colleague’s outstretched hand. I took a spoon from the table. Uri did not touch it. I put it on my colleague’s hand and asked Uri to bend it. Uri ran his finger above the spoon and stood back. Nothing happened. We expressed some disappointment, still watching the spoon. He said, “Wait and watch.” Slowly, as we watched, with Uri standing well away, the spoon started to curl in front of us, and within four minutes the tail of the spoon had risen up like a scorpion’s sting. I then took the spoon, the first time I had handled it since I put it there, and sure enough, it remained a normal spoon with a marked bend.’

Uri being tested at an INSERM laboratory in France.

Dr Wernher von Braun, the NASA scientist and father of the US space programme, met Uri and announced: ‘Geller has bent my ring in the palm of my hand without ever touching it. Personally, I have no scientific explanation for the phenomena.’ The MIT physics professor Gerald Schroeder, latterly of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, had a different slant on the Geller enigma. ‘What makes me accept Geller at face value,’ he said, ‘is that unlike a magician, he does not have a bag of tricks. He bends spoons. The one he bent with me peering over his shoulder continued to bend even after he placed it on the ground and stepped away. The Talmud claims there are two types of “magic”. One is the “catching of the eye”, an optical illusion. The other is the real thing, a mustering of the forces of nature. With Uri, I opt for the latter, though he claims he has no idea how these are mustered.’

But after all, perhaps it is possible, even for someone desperately anxious to be taken seriously by science, to become worn out by being a lab rat. ‘The government saw that they couldn’t really control me,’ Uri Geller says, ‘because I was really on an ego trip and into making money and into show business. I didn’t want to sit in a laboratory any more, doing the same thing again and again, without getting paid, and then getting constantly abused in the background by the sceptics with their silly, far-fetched explanations of what I did. Some of these people were really low – ignorant and lying, like medieval witch finders.’