The Secret Life of Uri Geller (9 page)

Read The Secret Life of Uri Geller Online

Authors: Jonathan Margolis

Tags: #The Secret Life of Uri Geller: Cia Masterspy?

‘I answered to some yes, to some no. And then to the ones that I said yes to, he arranged for me to execute those requests, and those I cannot talk about. Not to be too specific, I think one of the interesting questions was whether my mind could knock out a pilot’s mind in flight. Whether I could beam my powers and somehow mix up or jumble up a fighter pilot’s mind.’ The only actual task Uri speaks about from this time was successfully locating a piece of antique pottery for Dayan at an archaeological dig. Dayan would ask him to do the same again on other occasions, an offence under Israeli law, but not one he would be prosecuted for by anybody.

A variety of sources agree that the Israelis were intellectually open to the military and intelligence potential of Geller years before the USA, and the value Israel continues to place on Uri today cannot be underestimated. His work for the land of his birth is the area that he is the most reticent to discuss, perhaps because it is ongoing. The one thing he will say is that if he does anything for Israel, and he’s not necessarily saying he does, ‘it is only for totally positive causes’.

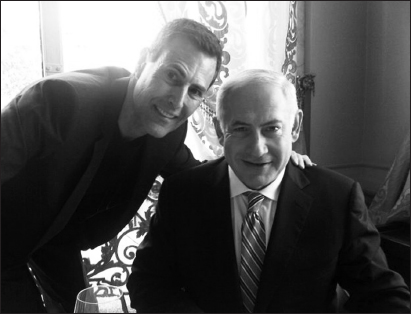

One slightly younger soldier whom Uri met when still in uniform and doing a performance is the current Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. The two remain close and see each other regularly. ‘His abilities made a tremendous impression on me as a young soldier,’ Netanyahu says today. ‘I’m still amazed, I haven’t a clue how he does these things.’ And it is Netanyahu, listed 23rd on the 2012

Forbes

magazine list of ‘The World’s Most Powerful People’, who tells one of the more remarkable stories of Uri’s metal-bending prowess. Netanyahu and his wife, Sara, were with Uri in a restaurant in Caesarea when Uri

simultaneously

bent the spoons of a whole group of people, all of whom were sitting at different tables – a rare example of a batch bending that caused astonishment in the restaurant.

Uri with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

As we know from Kit Green’s account in the previous chapter, back in the early 1970s, the Mossad was keen to swap intelligence with the USA, to the extent that it alerted the Americans to the unusual young man and told them that it was willing to allow the US intelligence and scientific communities to take a look at him. The Mossad’s overture was followed by Andrija Puharich’s mission to Israel to do semi-formal testing on Uri, and his eventual arrival in the USA in 1972.

During the two intense years that followed, the espionage world only touched Uri insofar as the circus that was going on around him. Mossad people were watching the SRI: CIA people were watching the SRI: and, according to a book on the Mossad written in 1978 by the well-informed writer Richard Deacon, various Soviet-bloc spooks were watching them all. Uri had only a hazy knowledge of what was going on. He was not privy to the increasing interest being taken in him as a possible intelligence asset. As he says himself, he was becoming more and more interested in being a celebrity and making a lot of money.

* * *

The period when Uri Geller begins being used by the CIA – an unprecedented development since he was still an Israeli citizen – as well as by Mossad and the Mexican government – begins around 1974.

There was reluctance and caution at the CIA even then to exploit Geller. ‘As we finished our work with Uri at SRI,’ says the former astronaut Edgar Mitchell, ‘I was called by the head of the CIA and asked to come to Washington and brief him on what we had learned. That head happened to be Ambassador George HW Bush’ [who later, of course, became president]. Mitchell explained to Bush that the Russians were studying parapsychology, so it was essential that the CIA should be studying it, too. Geller was not immediately recruited as an agent, but Kit Green began regularly talking with Eldon Byrd about the Geller question.

Eldon Byrd, the naval strategic weapons systems specialist who had been one of many experts investigating Uri on behalf of the military, also briefed a CIA director, whom he didn’t identify as Bush. ‘In later years during the Brezhnev period,’ he said before his death in 2002, ‘I met with several Russian scientists who not only had documented results similar to ours, but also were actively using psychic techniques against the USA and its allies. I eventually ended up briefing a director of the CIA. I also briefed people on the National Security Council and I briefed Congressional committees because of some of the results we got.’

Byrd recalled getting a request from Green to come and see them. He again did not reveal Green’s identity when interviewed. ‘I went down to Virginia, and they said we understand you had an interaction with Uri a couple of years ago, and what did you do with him?’ Byrd briefed Green and others at a meeting about some work he had done with Uri and a new, then secret, alloy of nickel and titanium called nitinol. Nitinol had a unique property of having a mechanical memory; it sprang back to the shape at which it was forged, whatever twisting and distortion it was subjected to. Byrd had given Uri a 12.5-centimetre-long piece of nitinol wire. Uri stroked it whereupon, according to Byrd, an odd little lump formed in it, which failed to disappear as it should have done. Bent nitinol, in Uri’s hands, also refused to spring back into its original shape. In this and further tests with the alloy, Uri produced a molecular-level effect in it which, the lab reported, would have required Geller to have raised the temperature of the metal to almost 500°C.

Green’s team at Langley was interested in this, as well they might be, but it was telepathy they seemed keener to discuss, and Byrd had some interesting experiences to relate. ‘Uri had written something on a piece of paper, handed it to me and said, “Put this in your hand and don’t look at it now. I’m going to think of a letter, and I want to see if you can pick it up.” He closed his eyes, but nothing was happening in my head. So I thought, maybe I have to close my eyes for this to work. I closed them, and bam, there’s a big green R lit up in my head. So I said, “I guess it’s an R,” and he said, “Yes, open the paper,” and it was an R. When Byrd had got home that night, he reported to Green, he and his wife, Kathleen, were up until late transmitting increasingly complex pictures to one another flawlessly. ‘I thought, man, somehow Uri tuned me up and I can even transfer the ability to my wife. But the next day, we tried again, and it wouldn’t work.’

One of the areas the CIA, and soon the military too, was most interested in at this time was teaching people to develop their own telepathic – and possibly even psychokinetic – powers, so they were all ears at what Byrd had to say. ‘I told him about the telepathy,’ he recalled, ‘and they said, “So you say it was a green R that came in your head?” I said, “Yes”, and they looked at each other. I asked if there was something significant about the colour and they said there was.

‘Another time,’ Byrd continued, ‘Uri asked me to check with my CIA guy, because he was living in the States and had the benefit of being here, and wanted to do something like work for the CIA on a project or something. So I passed that along to them and they said, “No! We won’t do that”. I said, “He’s offering for free, why not?” They said that they had had bad experiences working with double agents. “So we don’t do it.” They told me that they knew he was working with the Mossad. I said he’d never told me he was working with the Mossad. There had been a couple of instances of requests, but that didn’t mean working with or working for. “No!’ they said. “We know he works with the Mossad.”

‘Later on, my contact person, who was head at the time of a division called Life Sciences [who we now know was Green] was regularly asking me if I knew where Uri was and what he was doing. Finally, I asked, “Why are you so curious?” They said they were assigned to keep track of him. I said this implies that you know he’s for real. “Of course we know he’s for real,” they said, and went on to tell me that they’d tested him without his knowing who they were.’ (This, of course, relates to the home experiment Green recounts in

Chapter 1

.)

Green told Byrd that he had seen a tape of Uri cheating, but it didn’t make much difference, because they had seen him make spoons and forks bend on their own, so they were convinced that he was genuine. But this time, they were taping it under a certain set of protocols, and they said the proof to them that Uri was not a magician was that when they caught him cheating, the way he did it was so naïve that a magician wouldn’t have thought he could get away with it.

The question of whether Uri has ever cheated or used a bit of sleight of hand, to please experimenters – or audiences – remains a tricky one. He vehemently denies it to this day, apart from one instance back in Israel, on which he is completely open. But there are those, including his most influential proponent, Green, who believe he may have enhanced his effects at times when his powers were at a low ebb, as they occasionally were. Many who know him have suggested that Uri does occasionally use a bit of sleight of hand. It seems to be something he does with no great skill to muddy the waters around him and create controversy. He appears to enjoy lowering people’s expectations by doing a fairly obvious bit of routine magic – and then, when they have decided he’s just a trickster, hitting them with something truly inexplicable. He even sometimes says he sees this as a safety mechanism. ‘If you think about it, I probably would have been eliminated years ago if it was unanimously agreed that I was real,’ he says.

(Green’s opinion that when Uri did cheat, he did so, as others have noted, like a pretty hopeless amateur magician – rather than the skilled one his detractors claim he is – is an interesting one. Remember Russell Targ’s experience when he witnessed how Uri handled cards clumsily? Another view often proposed by students of Uri is that all sorts of professionals cut corners in various ways without negating the essential substance of their core ability. The Argentinian footballer Diego Maradona once scored a crucial goal against England by illegally touching the ball with his hand, and while it wasn’t exactly a glorious episode in his career, nobody seriously says he is a fraud who can’t play football at all; despite his obvious foul, he is commonly regarded as one of the most gifted players of all time. It might be added that the seven-times Tour de France winner Lance Armstrong was actually a pretty fine cyclist even without the performance-enhancing drugs that brought his career crashing down.)

Another figure on the American military/espionage landscape who was seriously assessing Uri Geller’s warfare potential in the early 1970s was John B. Alexander, a special forces colonel engaged, as Eldon Byrd was for the Navy, in exploring on the US Army’s behalf the paranormal’s potential as a non-lethal military weapon. Alexander – who is widely (but incorrectly) regarded as the character played by George Clooney in

The Men Who Stare At Goats

had commanded undercover military teams in Vietnam and Thailand, and later moved into military science, working as Director of the Advanced Systems Concepts Office, US Army Laboratory Command, then Chief of Advanced Human Research with INSCOM, the intelligence and security command.

On retirement in 1988, Alexander joined Los Alamos National Laboratory with a brief to develop the concept of non-lethal defence. With his rare PhD in thanatology – the scientific study of death – he has strongly believed for a long while that inducing recoverable disease in an enemy’s troops is preferable to blowing their bodies apart. He has written in this respect in several defence publications, including

Harvard International Review

and

Jane’s International Defence Review

, and been written about in publications from

The Wall Street Journal

to

Scientific American

.

John Alexander now runs a privately funded science consultancy in Nevada, and he is a powerful advocate both of psychokinesis (PK) as a genuine phenomenon and of Geller as the possessor of PK abilities.

‘I originally thought it could be a trick, but I dismissed that later,’ Alexander says today. ‘We even had magicians involved in looking at Geller. The idea of him relying on sleight of hand is nonsense. He is, of course, extremely gregarious and an extreme extrovert, and that worked against him, although had he not been an extrovert, the chances are that nobody would have heard of him.

‘From the military perspective,’ he continues, ‘Macro PK [like spoon bending] was of interest to some of us. The smart-ass question from the sceptics would usually be, “What are you going to do, bend tank barrels?” I always felt that showed their limited ability to think about topics that exceeded their realm of knowledge. My response was, “No! I think what we’re going to go after are computers.” If we believed that PK was real, and some of us did, then the threat was to moving small numbers of electrons, not large objects. That was the most energy efficient concept.’

There was no need, Alexander explained, to take every computer down. ‘All you have to do is make them unreliable, because everything we have is based on computer models and applications. So if you get to when you don’t trust those computers and, basically, everything we run now on digital information, that would be really significant. We couldn’t explain the process by which PK might influence computers. But we did theorize that unlike hit-to-kill mechanisms, PK had an additional advantage. That is, it didn’t have to work every time. Making weapons and sensor systems unreliable would be sufficient to have a devastating effect on the battlefield. Some took us seriously, others did not. At any rate, a few experiments were actually conducted after those of us involved either retired or moved to other assignments.’