The Secret Life of Uri Geller (22 page)

Read The Secret Life of Uri Geller Online

Authors: Jonathan Margolis

Tags: #The Secret Life of Uri Geller: Cia Masterspy?

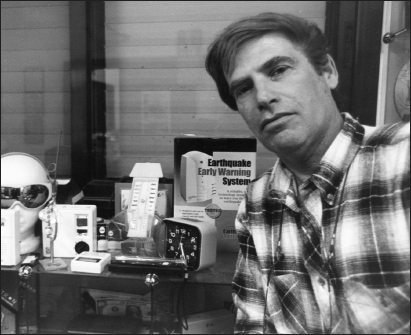

Uri’s friend Meir Gitlis, the first person to test his abilities scientifically.

‘I once asked a neurologist I know what he thought the mechanism might be, how Uri works,’ Gitlis adds. ‘He told me that he believed the two halves of our brain transmit to one another on a certain frequency of some kind, and than Uri may have the ability to tune in to frequencies that are not his own, that his brain is like a scanner for these brain transmissions. He believes a very small number of people have this ability.’

It was, then, with Meir’s small-scale, informal scientific experiments in mind as an example of how lab testing might be, that Uri spent much of his time in 1970 considering whether and how he might give a part of himself to science. It was no small matter that his show business career in Israel was beginning to fade to black at this time.

‘I started ebbing away in Israel,’ he acknowledges. ‘My performances had a limit. I could do telepathy. I could bend a spoon. I could warp rings. I could hypnotize a little. And that’s where it ended. A magician could write new acts, get new magic, do new tricks. I couldn’t because I wasn’t a magician. I was amazed when I started seeing the auditoriums emptying on me. 1971 was as incredible for me as 1970 had been, but already I was being attacked and questioned. 1972 was when I was over and out. People had seen me over and over, they were shouting, “Hey, Uri, we’ve seen that.” Managers could no longer put me up in big theatres, so I started being booked into discotheques and nightclubs, underground, smoky places, with dancing and striptease and clowns, jugglers and acrobats. I was suddenly just another act. No one would pay attention to me, and I really felt the pits.’

I WANNA BE IN AMERICA

I

n

Chapter 1

, we met the unconventional Serbian-American medical doctor and physicist, Andrija Puharich, who came to Tel Aviv in 1971 to gain some initial scientific perspective on Uri Geller as a precursor to him possibly coming for formal laboratory testing in the US. Puharich was a friend of the Moon-walking Apollo astronaut, Edgar Mitchell, and it was officially on behalf of Mitchell’s own research institute that Puharich was in Israel. In reality, Uri was being previewed, one might put it, by the CIA. Puharich claimed that he had worked for the Agency before, in 1948, on a US Navy initiative, ‘Project Penguin’ to test individuals said to possess psychic powers.

Andrija Puharich proved to be a both a blessing and a curse for Geller.

There is no doubt that it was because of Puharich that Uri came to America and embarked on the extraordinary period which led to him featuring in the leading scientific journals of the day, having private meetings with a president, spooking out a bunch of nuclear scientists so badly that they quit their jobs, becoming friends with a group as diverse as John Lennon, Salvador Dali and Muhummad Ali – and undertaking psychic missions for the CIA and the FBI.

However, it was also under the Svengali-like spell of Puharich that Uri became immersed in a world so weird that it would be an extravagantly gift-wrapped present to his sceptical detractors. But at least he escaped the fate of a previous ‘project’ of Puharich, an environmental activist and peacenik called Ira Einhorn who became a notorious murderer and fugitive from justice. Aged 73, Einhorn is still serving a life sentence without parole for murder.

So who or what was Puharich? He has been described as ‘deeply eccentric’ and ‘bordering on the paranoid’. But if one word were needed to describe him, it would have to be ‘polymath’. At school, he was an academic and sports star, excelling in the wrestling ring. He went on to do a first degree in philosophy at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, working his way through college as a tree surgeon, before entering the University’s medical school in 1943. His first medical assignment was as a second lieutenant in the US Army Medical Corps. He became deeply interested in parapsychology and ESP from the start of his medical career, but continued to lecture and publish papers on conventional medicine, too. He was also a formidable electronics genius, who hero-worshipped and modelled himself on another Serbian-American, the brilliant inventor, Nikola Tesla. And he was far from averse to a bit of fun; Puharich once played himself as a psychic investigator in an episode of the TV series

Perry Mason

, called ‘The Case of the Meddling Medium’.

Just like Tesla, Puharich was megalomaniacal, neurotic, obsessive, manipulative and self-destructive. Just as Tesla did, Puharich patented dozens of inventions, many based on the newly discovered transistors and silicon chips. Among his patents were micro in-ear hearing aids that worked by electrically stimulating nerve endings in the bones of the skull, a device for splitting water molecules, and a shield for protecting people from the health effects of ELF (Extremely Low Frequency) magnetic radiation from the natural environment. Like Tesla, Puharich was adept at living royally on other people’s money, although both men died in abject poverty. Both men also enjoyed the company of leading literary figures of their respective days: Tesla with Mark Twain and Rudyard Kipling; Puharich, 50 years later, with the novelist, Aldous Huxley.

In 1954, while the 60-year-old Huxley, who had been born in Godalming, Surrey, was living in California, he published his best-known work after

Brave New World

–

The Doors Of Perception

, an account of his tripping on the drug mescalin. The book became a bible of 60s’ counterculture. Huxley borrowed the title from the poet, William Blake, and it, or part of it, in turn was borrowed in turn by a rock musician called Jim Morrison as the name for his new band – The Doors. And it was Andrija Puharich, the man who discovered Uri Geller for America, who introduced Aldous Huxley to drugs. Mescalin blew Huxley’s mind, just as, nearly two decades later, Uri Geller, or so it seems, blew Puharich’s mind – more or less permanently – and without using drugs at all. Paradoxically, since Puharich is so linked in the hippy consciousness with exotic substances, his new Israeli discovery, nice, neurotic Jewish boy that he was, was scared of both alcohol and narcotics and has always stringently avoided them.

At the time he sought out Uri in Israel, Puharich had adopted a rumpled Einstein look, frizzy-haired with a crooked bow tie. But in the 60s, when he first became well known in some sections of American society, he was an intense, handsome doctor, renowned as an author of books on the paranormal and as an occasional face on television. He served in the army again in the early 1950s, and in 1952, presented a paper entitled

An Evaluation of the Possible Uses of Extrasensory Perception in Psychological Warfare

at a secret Pentagon meeting. In 1953, he lectured senior US Air Force officers on telepathy, and the staff of the Army Chemical Center on ‘The Biological Foundations of Extrasensory Perception.’

Puharich first heard of his protégé as a result of a lecture Uri gave to science students in the spring of 1970 at the Technion – the Israel Institute of Technology – in Haifa. When a retired Israeli army colonel named Yacov, who had heard about the lecture contacted a fellow Israeli researcher friend in Boston, Isaac Bentov, about Geller, Bentov wanted to know more. Uri liked the colonel and broke an ordinary little pin the man had while it was in his fist. The colonel mailed the broken pieces to Bentov in the States, who found something of interest in the structure of the break in the mild steel. Bentov talked about Uri at a November 1970 conference in New York for ‘alternative’-type scientists, called ‘Exploring The Energy Fields of Man’.

Delegates at the conference, Puharich among them, had been bemoaning the lack of a scientifically validated exponent of psychokinesis, Now in search of a new project, Puharich was soon on his way to Israel (and a discreetly hidden Mossad welcoming committee briefed to monitor what he was doing with ‘their’ Uri Geller) with a truckload of laboratory equipment and a mandate from the CIA to let them know what he found.

In 1971, while he had been raising funds for his Uri Geller fact finding trip, Puharich, had twice met Edgar Mitchell, the lunar module pilot for the Apollo 14 Moon mission. After serving as a back-up crew member for Apollo 16, Ed Mitchell retired and went full time into psychic and parapsychological research, writing a massive scientific book,

Psychic Exploration: A Challenge For Science

, and thereby earning himself the epithet ‘half-assed-tronaut’ from his non-admirers among the more crusading scientist and magician sceptics. The retired astronaut wrote to Uri recommending Puharich and enclosing a signed photograph of himself on the Moon. Uri had been obsessed with space travel even before there was such a thing and the very mention of Edgar Mitchell was enough to get him onboard for his first semi-formal, lab-rat duties.

It was, therefore, with some hope that Andrija Puharich found himself at 11pm on a hot Tuesday night in Zorba, a seedy Old Jaffa nightclub, watching Uri Geller perform as the climax to a succession of second-rate singers, jugglers and other cabaret turns – and being distinctly underwhelmed by what he saw. Geller knew from Mitchell’s letter that Puharich was coming, but had not expected him to turn up at Zorba, and was embarrassed when he did. Puharich admitted to Uri months later that he was pretty sure at the end of his evening at Zorba that Uri was no more than a routine magician, and that he may well have wasted his trip from the States.

Puharich, although every inch the hippy icon, was not necessarily a credulous individual. The year before he discovered Uri, he had been to Canada to meet Arthur Matthews, an 80-year-old man who had just published a book called

Nikola Tesla and the Venusian Space Ship

. It was Matthews’ contention that Tesla, Puharich’s exemplar, had not died as history recorded, in 1943, but was living aboard a UFO, which occasionally landed in Matthews’ back yard. And it was Puharich’s professional opinion after meeting him that Matthews was quite insane.

Initially dubious though he was of Uri Geller, too, Puharich installed himself in a friend’s apartment, and over the next few days did some preliminary tests with Geller. Puharich, it seems, was determined to ‘get a result’ if there was one to get. He did so with the reputation and methods of the proper, pedantic scientific researcher that he was capable of being. He kept the most meticulous notes in a tiny handwriting on his Geller experiments, all of which were airmailed back to Edgar Mitchell. Precision note taking was second nature to Puharich; no tape recorder or film camera could be mentioned without its make and model number being logged; all times were accurately recorded to the second.

The events Puharich reported did, nonetheless, resemble a reprise of Aldous Huxley’s drug-tripping research – and this was

before

Puharich’s work in Israel with Geller turned seriously bizarre, as it soon did. It started routinely. Puharich explained to Uri that the tests would be lengthy and occasionally boring, but that this was necessary, thanks to the scientific convention that extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof. With Yacov, the retired colonel, and an Israeli woman friend as assistants, Puharich asked Uri what he would like to do first.

Uri suggested some simple telepathy. He wrote something on a pad, placed it face down on the table and asked Puharich to think of a number, then another, then another. Uri then asked him to pick the pad up. On it were already written the numbers, ‘4’, ‘3’ and ‘2’, which Puharich had in his mind. Uri laughed, apparently delighted that it had worked. Like Amnon Rubinstein had been, Puharich was immediately more impressed with that than by the spoon bending, which he had seen at the nightclub and regarded as inconclusive. ‘That’s pretty clever,’ Puharich reports he said. ‘You told me this would be telepathy, and I, of course, thought you were going to be the receiver. But you pulled a switch on me.’

Uri explained why he had done it this way round, by saying that if he had told Puharich to try to receive the numbers, he might have fought him. ‘In this way, you participated in the experiment without prejudice,’ he said. Puharich asked if he could turn on the tape recorder and the camera. Geller assented, but added, ‘You probably think that since I sent those numbers to you so easily, I might also hypnotize you to see and do things that are not really there.’

Puharich reported that he felt from that point the two of them would get along fine, although for several days more their relationship would remain formal, Uri calling him ‘Dr Puharich’. After an hour of swapping numbers, colours and single words telepathically, Puharich and his assistants got into a huddle and agreed that, even if this obviously was not a proper, controlled experiment, they were satisfied that this was genuine telepathy. They asked if he could receive or transmit more complex data; he replied that he stuck to simple information, because then he could be judged wholly right or wholly wrong, with no grey area, as would be bound to occur if he tried to transfer whole concepts or stories.

Uri then asked if anyone had brought a broken watch. Yacov’s friend said she had one which was not broken, but which she had allowed to run down and stop. Puharich intervened and asked to inspect it. With the camera running, he shook the watch, and it ticked for a few seconds, then stopped completely. Uri refused to touch it, and told Puharich to give it straight back to the woman. He placed it in her palm, which she closed. Uri then put his left palm over her hand, without, Puharich said, touching it. After 30 seconds, the watch was running, and continued to work for another 30 minutes before running down again. Meanwhile, Uri asked Puharich to take off his watch, a chronometer, and hold it in his hand. Puharich noted the time on it as 2.32pm, and then Uri held his hand over Puharich’s for ten seconds and told Puharich to check it. The time on the watch was now 3.04; but what surprised Puharich more was that the stopwatch dial on the watch face had similarly advanced 32 minutes. For both dials to have advanced by the same time, the whole apparatus would simply have to have run for 32 minutes. ‘This complex feat of psychokinesis was unparalleled in my experience, or in the literature, for that matter,’ Puharich concluded.