The Story of the Greeks (Yesterday's Classics) (3 page)

This promise was duly kept, and Xuthus the exile ruled over Athens. When he died, he left the crown to his sons, Ion and Achæus.

As the Athenians had gradually increased in number until their territory was too small to afford a living to all the inhabitants, Ion and Achæus, even in their father's lifetime, led some of their followers along the Isthmus of Corinth, and down into the peninsula, where they founded two flourishing states, called, after them, Achaia and Ionia. Thus, while northern Greece was pretty equally divided between the Dorians and Æolians, descendants and subjects of Dorus and Æolus, the peninsula was almost entirely in the hands of Ionians and Achæans, who built towns, cultivated the soil, and became bold navigators. They ventured farther and farther out at sea, until they were familiar with all the neighboring bays and islands.

Sailing thus from place to place, the Hellenes came at last to Crete, a large island south of Greece. This island was then governed by a very wise king called Minos. The laws of this monarch were so just that all the Greeks admired them very much. When he died, they even declared that the gods had called him away to judge the dead in Hades, and to decide what punishments and rewards the spirits deserved.

Although Minos was very wise, he had a subject named Dædalus who was even wiser than he. This man not only invented the saw and the potter's wheel, but also taught the people how to rig sails for their vessels.

As nothing but oars and paddles had hitherto been used to propel ships, this last invention seemed very wonderful; and to compliment Dædalus, the people declared that he had given their vessels wings, and had thus enabled them to fly over the seas.

Many years after, when sails were so common that they ceased to excite any wonder, the people, forgetting that these were the wings which Dædalus had made, invented a wonderful story, which runs as follows.

Minos, King of Crete, once sent for Dædalus, and bade him build a maze, or labyrinth, with so many rooms and winding halls, that no one, once in it, could ever find his way out again.

Dædalus set to work and built a maze so intricate that neither he nor his son Icarus, who was with him, could get out. Not willing to remain there a prisoner, Dædalus soon contrived a means of escape.

Dædalus and Icarus

He and Icarus first gathered together a large quantity of feathers, out of which Dædalus cleverly made two pairs of wings. When these were fastened to their shoulders by means of wax, father and son rose up like birds and flew away. In spite of his father's cautions, Icarus rose higher and higher, until the heat of the sun melted the wax, so that his wings dropped off, and he fell into the sea and was drowned. His father, more prudent than he, flew low, and reached Greece in safety. There he went on inventing useful things, often gazing out sadly over the waters in which Icarus had perished, and which, in honor of the drowned youth, were long known as the Icarian Sea.

The Adventures of Jason

T

HE

Hellenes had not long been masters of all Greece, when a Phrygian called Pelops became master of the peninsula, which from him received the name of Peloponnesus. He first taught the people to coin money; and his descendants, the Pelopidæ, took possession of all the land around them, with the exception of Argolis, where the Danaides continued to reign.

Some of the Ionians and Achæans, driven away from their homes by the Pelopidæ, went on board their many vessels, and sailed away. They formed Hellenic colonies in the neighboring islands along the coast of Asia Minor, and even in the southern part of Italy.

As some parts of Greece were very thinly settled, and as the people clustered around the towns where their rulers dwelt, there were wide, desolate tracts of land between them. Here were many wild beasts and robbers, who lay in wait for travelers on their way from one settlement to another. The robbers, who hid in the forests or mountains, were generally feared and disliked, until at last some brave young warriors made up their minds to fight against them and to kill them all. These young men were so brave that they well deserved the name of heroes, which has always been given them; and they met with many adventures about which the people loved to hear. Long after they had gone, the inhabitants, remembering their relief when the robbers were killed, taught their children to honor these brave young men almost as much as the gods, and they called the time when they lived the Heroic Age.

Not satisfied with freeing their own country from wild men and beasts, the heroes wandered far away from home in search of further adventures. These have also been told over and over again to children of all countries and ages, until every one is expected to know something about them. Fifty of these heroes, for instance, went on board of a small vessel called the "Argo," sailed across the well-known waters, and ventured boldly into unknown seas. They were in search of a Golden Fleece, which they were told they would find in Colchis, where it was said to be guarded by a great dragon.

The leader of these fifty adventurers was Jason, an Æolian prince, who brought them safely to Colchis, whence, as the old stories relate, they brought back the Golden Fleece. They also brought home the king's daughter, who married Jason, and ruled his kingdom with him. Of course, as there was no such thing as a Golden Fleece, the Greeks merely used this expression to tell about the wealth which they got in the East, and carried home with them; for the voyage of the "Argo" was in reality the first distant commercial journey undertaken by the Greeks.

Theseus Visits the Labyrinth

O

N

coming back from the quest for the Golden Fleece, the heroes returned to their own homes, where they continued their efforts to make their people happy.

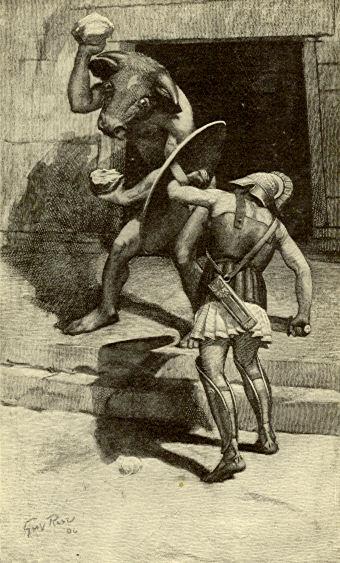

Theseus, one of the heroes, returned to Athens and founded a yearly festival in honor of the goddess Athene. This festival was called Panathenæa, which means "all the worshipers of Athene." It proved a great success, and was a bond of union among the people, who thus learned each other's customs and manners, and grew more friendly than if they had always stayed at home. Theseus is one of the best-known among all the Greek heroes. Besides going with Jason in the "Argo," he rid his country of many robbers, and sailed to Crete. There he visited Minos, the king, who, having some time before conquered the Athenians, forced them to send him every year a shipload of youth and maidens, to feed to a monster which he kept in the Labyrinth.

To free his country from this tribute, Theseus, of his own free will, went on board the ship. When he reached Crete, he first went into the Labyrinth, and killed the monster with his sword. Then he found his way out of the maze by means of a long thread which the king's daughter had given him. One end of it he carried with him as he entered, while the other end was fastened to the door.

Theseus and the Minotaur

His old father, Ægeus, who had allowed him to go only after much persuasion, had told him to change the black sails of his vessel for white if he were lucky enough to escape. Theseus promised to do so, but he entirely forgot it in the joy of his return.

Ægeus, watching for the vessel day after day, saw it coming back at last; and when the sunlight fell upon the black sails, he felt sure that his son was dead.

His grief was so great at this loss, that he fell from the rock where he was standing down into the sea, and was drowned. In memory of him, the body of water near the rock is still known as the Ægean Sea.

When Theseus reached Athens, and heard of his father's grief and sudden death, his heart was filled with sorrow and remorse, and he loudly bewailed the carelessness which had cost his father's life.

Theseus now became King of Athens, and ruled his people very wisely for many years. He took part in many adventures and battles, lost two wives and a beloved son, and in his grief and old age became so cross and harsh that his people ceased to love him.

They finally grew so tired of his cruelty, that they all rose up against him, drove him out of the city, and forced him to take his abode on the Island of Scyros. Then, fearing that he might return unexpectedly, they told the king of the island to watch him night and day, and to seize the first good opportunity to get rid of him. In obedience to these orders, the king escorted Theseus wherever he went; and one day, when they were both walking along the edge of a tall cliff, he suddenly pushed Theseus over it. Unable to defend or save himself, Theseus fell on some sharp rocks far below, and was instantly killed.

The Athenians rejoiced greatly when they heard of his death; but they soon forgot his harshness, and remembered only his bravery and all the good he had done them in his youth, and regretted their ingratitude. Long after, as you will see, his body was carried to Athens, and buried not far from the Acropolis, which was a fortified hill or citadel in the midst of the city. Here the Athenians built a temple over his remains, and worshiped him as a god.

While Theseus was thus first fighting for his subjects, and then quarreling with them, one of his companions, the hero Hercules (or Heracles) went back to the Peloponnesus, where he had been born. There his descendants, the Heraclidæ, soon began fighting with the Pelopidæ for the possession of the land.

After much warfare, the Heraclidæ were driven away, and banished to Thessaly, where they were allowed to remain only upon condition that they would not attempt to renew their quarrel with the Pelopidæ for a hundred years.

The Terrible Prophecy

W

HILE

Theseus was reigning over the Athenians, the neighboring throne of Thebes, in Bœotia, was occupied by King Laius and Queen Jocasta. In those days the people thought they could learn about the future by consulting the oracles, or priests who dwelt in the temples, who pretended to give mortals messages from the gods.

Hoping to learn what would become of himself and of his family, Laius sent rich gifts to the temple at Delphi, asking what would befall him in the coming years. The messenger soon returned, but, instead of bringing cheerful news, he tremblingly repeated the oracle's words: "King Laius, you will have a son who will murder his father, marry his mother, and bring destruction upon his native city!"

This news filled the king's heart with horror; and when, a few months later, a son was born to him, he made up his mind to kill him rather than let him live to commit such fearful crimes. But Laius was too gentle to harm a babe, and so ordered a servant to carry the child out of the town and put him to death.

The man obeyed the first part of the king's orders; but when he had come to a lonely spot on the mountain, he could not make up his mind to kill the poor little babe. Thinking that the child would soon die if left on this lonely spot, the servant tied him to a tree, and, going back to the city, reported that he had gotten rid of him.

No further questions were asked, and all thought that the child was dead. It was not so, however. His cries had attracted the attention of a passing shepherd, who carried him home, and, being too poor to keep him, took him to the King of Corinth. As the king had no children, he gladly adopted the little boy.

When the queen saw that the child's ankles were swollen by the cord by which he had been hung to the tree, she tenderly cared for him, and called him Œdipus, which means "the swollen-footed." This nickname clung to the boy, who grew up thinking that the King and Queen of Corinth were his real parents.

The Sphinx's Riddle

W

HEN

Œdipus was grown up, he once went to a festival, where his proud manners so provoked one of his companions, that he taunted him with being only a foundling. Œdipus, seeing the frightened faces around him, now for the first time began to think that perhaps he had not been told the truth about his parentage. So he consulted an oracle.

Instead of giving him a plain answer,—a thing which the oracles were seldom known to do,—the voice said, "Œdipus, beware! You are doomed to kill your father, marry your mother, and bring destruction upon your native city!"