The Story of the Greeks (Yesterday's Classics) (6 page)

Achilles, who wanted to save the Greeks from the plague, allowed the maiden to depart, warning Agamemnon, however, that he would no longer fight for a chief who could be so selfish and unjust. As soon as the girl had gone, therefore, he laid aside his fine armor; and although he heard the call for battle, and the din of fighting, he staid quietly within his tent.

While Achilles sat thus sulking day after day, his companions were bravely fighting. In spite of their bravery, however, the Trojans were gaining the advantage; for, now that Achilles was no longer there to fill their hearts with terror, they fought with new courage.

The Greeks, missing the bright young leader who always led them into the midst of the fray, were gradually driven back by the Trojans, who pressed eagerly forward, and even began to set fire to some of the Greek ships.

Achilles' friend, Patroclus, who was fighting at the head of the Greeks, now saw that the Trojans, unless they were checked, would soon destroy the whole army, and he rushed into Achilles' tent to beg him to come and help them once more.

His entreaties were vain. Achilles refused to move a step; but he consented at last to let Patroclus wear his armor, and, thus disguised, make a last attempt to rally the Greeks and drive back the Trojans.

Patroclus started out, and, when the Trojans saw the well-known armor, they shrank back in terror, for they greatly feared Achilles. They soon saw their mistake, however; and Hector, rushing forward, killed Patroclus, tore the armor off his body, and retired to put it on in honor of his victory.

Then a terrible struggle took place between the Trojans and the Greeks for the possession of Patroclus' body. The news of his friend's death had quickly been carried to Achilles, and had roused him from his indifferent state. Springing upon the wall that stretched before the camp, he gave a mighty shout, at the sound of which the Trojans fled, while Ajax and Ulysses brought back the body of Patroclus.

Death of Hector and Achilles

T

HE

next day, having secured his armor and weapons, Achilles again went out to fight. His purpose was to meet Hector, and, by killing him, to avenge his dead friend, Patroclus. He therefore rushed up and down the battlefield; and when at last he came face to face with his foe, they closed in deadly fight. The two young men, each the champion warrior of his army, were now fighting with the courage of despair; for, while Achilles was thirsting to avenge his friend, Hector knew that the fate of Troy depended mostly upon his arm. The struggle was terrible. It was watched with breathless interest by the armies on both sides, and by aged Priam and the Trojan women from the walls of Troy. In spite of Hector's courage, in spite of all his skill, he was doomed to die, and soon he fell under the blows of Achilles.

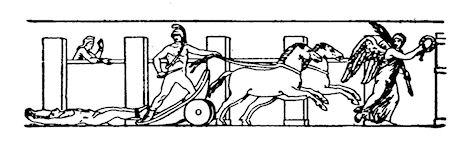

Then, in sight of both armies and of Hector's weeping family, Achilles took off his enemy's armor, bound the dead body by his feet to his chariot, and dragged it three times around the city walls before he went back to camp to mourn over the remains of Patroclus.

That night, guided by one of the gods, old King Priam came secretly into the Greek camp, and, stealing into Achilles' tent, fell at his feet. He had come to beg Achilles to give back the body of Hector, that he might weep over it, and bury it with all the usual ceremonies and honors.

Touched by the old man's tears, and ready now to listen to his better feelings, Achilles kindly raised the old king, comforted him with gentle words, and not only gave back the body, but also promised that there should be a truce of a few days, so that both armies could bury their dead in peace.

The funerals were held, the bodies burned, the usual games celebrated; and when the truce was over, the long war was begun again. After several other great fights, Achilles died from a wound in his heel caused by a poisoned arrow that was treacherously shot by Paris.

The sorrowing Greeks then buried the young hero on the wide plain between Troy and the sea. This spot has been visited by many people who admired the brave young hero of the Iliad.

The Burning of Troy

A

S

the valor of the Greeks had proved of no avail during the ten-years' war, and as they were still as far as ever from taking Troy, Ulysses the crafty now proposed to take the city by a stratagem, or trick.

The Greeks, obeying his directions, built a wooden horse of very large size. It was hollow, and the space inside it was large enough to hold a number of armed men. When this horse was finished, and the men were hidden in it, the Greeks all embarked as if to sail home.

The Trojans, who had watched them embark and sail out of sight, rushed down to the shore shouting for joy, and began to wander around the deserted camp. They soon found the huge wooden horse, and were staring wonderingly at it, when they were joined by a Greek who had purposely been left behind, and who now crept out of his hiding place.

In answer to their questions, this man said that his companions had deserted him, and that the wooden horse had been built and left there as an offering to Poseidon (or Neptune), god of the sea. The Trojans, believing all this, now decided to keep the wooden horse in memory of their long siege, and the useless attempt of the Greeks to take Troy.

They therefore joyfully dragged the huge animal into the city; and, as the gates were not large enough for it to pass through, they tore down part of their strong walls.

That very night, while all the Trojans were sleeping peacefully for the first time in many years, without any fear of a midnight attack, the Greek vessels noiselessly sailed back to their old moorings. The soldiers landed in silence, and, marching up softly, joined their companions, who had crept out of the wooden horse, and had opened all the gates to receive them.

Pouring into Troy on all sides at once, the Greeks now began their work of destruction, killing, burning, and stealing everywhere. The Trojan warriors, awakening from sleep, vainly tried to defend themselves; but all were killed except Prince Æneas, who escaped with his family and a few faithful friends, to form a new kingdom in Italy.

All the women, including even the queen and her daughters, were made prisoners and carried away by the Greek heroes. The men were now very anxious to return home with the booty they had won; for they had done what they had long wished to do, and Troy, the beautiful city, was burned to the ground.

Vase

All this, as you know, happened many years ago,—so many that no one knows just how long. The city thus destroyed was never rebuilt. Some years ago a German traveler began to dig on the spot where it once stood. Deep down under the ground he found the remains of beautiful buildings, some pottery, household utensils, weapons, and a great deal of gold, silver, brass, and bronze. All these things were blackened or partly melted by fire, showing that the Greeks had set fire to the city, as their famous old poems relate.

Jug

The Greeks said, however, that their gods were very angry with many of their warriors on account of the cruelty they showed on that dreadful night, and that many of them had to suffer great hardships before they reached home. Some were tossed about by the winds and waves for many long years, and suffered shipwrecks. Others reached home safely, only to be murdered by relatives who had taken possession of their thrones during their long absence.

Cup

Only a few among these heroes escaped with their lives, and wandered off to other countries to found new cities. Thus arose many Greek colonies in Sicily and southern Italy, which were called Great Greece, in honor of the country from which the first settlers had come.

As you have already seen, Prince Æneas was among these Trojans. After many exciting adventures, which you will be able to read in the "Story of Rome," he sailed up the Tiber River, and landed near the place where one of his descendants was to found the present capital of Italy, which is one of the most famous cities in the world.

Heroic Death of Codrus

Y

OU

remember, do you not, how the sons of Pelops had driven the Heraclidæ, or sons of Hercules, out of the peninsula which was called the Peloponnesus? This same peninsula is now called Morea, or the mulberry leaf, because it is shaped something like such a leaf, as you will see by looking at your map.

The Heraclidæ had not gone away willingly, but were staying in Thessaly, in the northern part of Greece, where they promised to remain one hundred years without making any attempt to come back.

Shortly after the end of the Trojan War, this truce of a hundred years came to an end; and the Heraclidæ called upon their neighbors the Dorians to join them, and help them win back their former lands.

Led by three brave chiefs, the allies passed through Greece proper, along the Isthmus of Corinth, and, spreading all over the Peloponnesus, soon took possession of the principal towns. The leading members of the family of Hercules took the title of kings, and ruled over the cities of Argos, Mycenæ, and Sparta.

The Dorians, who had helped the Heraclidæ win back their former possessions, now saw that the land here was better than their home in the mountains, so they drove all the rest of the Ionians out of the country, and settled there also.

Thus driven away by the Dorians and the Heraclidæ, these Ionians went to Athens, to the neighboring islands, and even to the coast of Asia Minor, south of the ruined city of Troy, where they settled in great numbers. They called the strip of land which they occupied Ionia, and founded many towns, some of which, such as Ephesus and Miletus, were destined to become famous.

Of course, the Ionians were very angry at thus being driven away from home; and those who had gone to live in Athens soon asked Codrus, the Athenian king, to make war against the Heraclidæ of Sparta.

The two armies soon met, and prepared for battle. Codrus, having consulted an oracle, had learned that the victory would be given to the army whose king should be killed, so he nobly made up his mind to die for the good of his people.