The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction (15 page)

Read The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction Online

Authors: Rachel P. Maines

Tags: #Medical, #History, #Psychology, #Human Sexuality, #Science, #Social Science, #Women's Studies, #Technology & Engineering, #Electronics, #General

One of the first technologies used for this purpose was a retrofit of the water-powered saw. Although there is no evidence these devices were ever applied to gynecological treatment, some writers assert that in ancient times the vibrating beam ends of water-powered saws were sometimes padded with fabric and used for massage.

3

More often, those seeking physical therapies in ancient and medieval times employed manual massage providers, as did Juvenal’s subject, or visited baths with appliances for pumping water under at least some pressure, even if only that of gravity. In 1734 one Abbé St. Pierre is reported to have invented a mechanical predecessor to the vibrator called a

trémoussoir

, but little is known about the use and configuration of this device.

4

Bathing and hygiene establishments offered simple adjuncts to manual massage at least as early as the Renaissance and possibly before (

fig. 8

), including hand-held beaters, kneaders, and brush-type stimulators of the kind now associated with saunas.

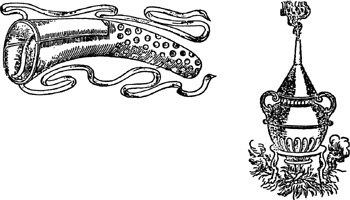

At the same time, there existed a set of technologies for treating vaginal and uterine disorders that necessarily overlapped with massage, since hysteria and chlorosis were both thought to be uterine in origin. Pessaries or suppositories containing Galenically cooling or heating ingredients, depending on the malady, could be prescribed. Another technique was subfumigation, illustrated in Paré, in which the patient sat over a small burner from which attractive or repellent fumes, again depending on the ailment, wafted upward into the vagina.

5

The efficacy of this method was thought to be enhanced by the use of perforated pessaries

that held the vagina open to permit passage of the odoriferous vapors (

fig. 9

).

6

F

IG.

8. Medieval bathing establishment. From Emmett Murphy,

Great Bordellos of the World

(1983), Bibliothèque Nationale.

As I indicated in

chapter 2

, massage of the vulva was a somewhat controversial practice among physicians after the medieval period, despite the treatment’s venerable history. In the nineteenth century, the conflict and ferment of ideas about women and their physicians brought these debates into unaccustomed prominence. Public awareness of controversies among physicians had been growing steadily, of course, since the late Renaissance, when medical works began to abandon the international standard of Latin as the language of professional communication.

7

The trend was accelerated by the spread of inexpensive printing methods and materials that brought books within the economic reach of a much broader range of social classes in the nineteenth century. By 1890 the European or American lay reader of medical works had almost as many opportunities for exposure to medical confusion, controversy, and tendentious case studies as do modern viewers of television health programs. Although doctors had always attacked each other’s theories and practice in their professional literature, the print explosion of the nineteenth century set the debate over clinical issues before the reading public for the first time. Physicians with radical ideas about therapy, such as the hydropaths who abounded in nineteenth-century America, Britain, and Europe, were especially likely to take their case to the customer rather than to their medical colleagues, who regarded their claims as questionable at best.

The direct massage of the vulva in hysteria and related disorders remained substantially unchanged through the nineteenth century. There was, however, a difference in the way the subject was discussed in some of the medical literature, particularly in America and Britain. Physicians were less likely than their predecessors, who could draw the veil of Latin over their expositions, to dwell on the details of their manipulations of the female genitalia, knowing that texts in the vernacular might well fall into the hands of the medically unqualified. Theodore Gaillaird Thomas mentioned gynecological massage treatments in a medical work published in Philadelphia in 1891, omitting any practical instructions on the grounds that “the details of the manipulations are too minute for reproduction here, and must be read in the original works,” some of which were in Latin.

8

The French author A. Sigismond Weber, however, showed no such delicacy in 1889 when he described vulvular massage, including details of both internal and external manipulation with the fingers, in a work on electricity and massage.

9

F

IG

. 9. Renaissance instruments for subfumigation. From Ambroise Paré,

L’opera ostetrico-ginecologica di Ambrogio Paré

, ed. Vittorio Pedore (Bologna: Cappelli, 1966), 166.

Although mechanisms of various kinds were available by the third quarter of the nineteenth century, not all advocates of physical therapies for hysteria endorsed them. George Massey, a well-known American physician who was actively involved in the development of electrotherapeutics, nonetheless considered “massage with the hand as the only efficient method” of treating hysterical women, “rejecting all machinery, muscle-beaters, etc., as either but poor substitutes for the hand of the

masseur

or as presenting an entirely different therapeutic measure.”

10

Silas Weir Mitchell, the rest-cure physician who has been identified as the antihero of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s

The Yellow Wallpaper

, was an advocate of massage; however, in 1877 he warned his fellow physicians that “the early use of massage is apt in some nervous women to cause increased nervousness and even loss of sleep,” though “very soon the patient begins to find the massage soothing and to complain when it is omitted.”

11

Mitchell may also have been the physician Thomas Low

Nichols referred to in his 1850 tract on the merits of the water cure for pregnant women:

One man—if I do not too much insult humanity in giving him that appellation—residing in the vicinity of New York, has made these female diseases a specialty … The infamy of his bold quackeries and obscene manipulations would make the paper blush on which it was written. I have known of case after case which he has maltreated; and I know of no case in which, after a time, and when the peculiar excitement he induces has lost its effect, the patient has not sunk into a worse condition.

12

HYDROPATHY AND HYDROTHERAPY

Bathing of all kinds, but especially at spas or public bathing establishments, has been associated with sexuality in Western culture since antiquity.

13

Medicinal immersion in hot springs probably predates the fifth century

B.C.

, and it was known in North America long before the arrival of Europeans. Native Americans are said to have discovered some of the hot springs and mineral springs on this continent by following the trails of animals that used them.

14

It was in Europe and Britain, and later in Europeanized America, that bathing spas acquired their reputation for luxury and dissipation. Gambling and beverages considerably stronger than mineral water were usually available at spas as alternatives to balneotherapy, or as entertainment for the companions of the afflicted.

15

Even the physicians were sometimes suspect: Francis Power Cobbe cast vague aspersions in 1881 on the morality of physicians who specialized in spa practice.

16

As late as the mid-twentieth century, Georges Simenon could plausibly suggest that gambling at spas counted as part of the therapy.

17

Iris Murdoch’s novel

The Philosopher’s Pupil

is set in the mythical bath town of Ennistone, which, according to the author, has a dark reputation for unmentionable vices.

18

The Roman baths are reported to have been important venues for prostitution, a point to which an eighteenth-century German writer drew attention when he declared England’s Bath and Tunbridge Wells the equals of the Caracalla in depravity.

19

Bath had by that time had a scandalous reputation for more than a hundred years. Despite (or perhaps

because of) this infamy, British royalty gamely visited the place: Queen Anne in 1616 and Queen Catherine in 1663, the latter in search, significantly enough, of a cure for infertility.

20

In Western Europe, long before the modern period, women went to mineral springs for such treatments as Catherine received at Bath.

21

Spas became fashionable even for the not very sick in Europe and Britain in the eighteenth century, and they reached fad proportions in the nineteenth. Tobias Smollett, who wrote an essay on the water cure in 1752, remarked that pumped water was good for “hysterical Disorders … Obstructions of the Menses, and all cases, where it is necessary to make a revulsion from the head, and to invite the juices downwards.” He was an enthusiastic supporter of hydrotherapy in obstetrics as well, observing that “besides these uses of the Warm Bath, it is of great service in promoting delivery, by relaxing the part in those women who are turned of thirty before the first child; and in such as are naturally contracted in consequence of a rigid fibre, and robust constitution.” He goes to commend a “Mr. Cleland, Surgeon” at Bath, who had proposed to the medical staff “a very ingenious apparatus he had contrived, for some complaints peculiar to the fair sex.” Unfortunately, Smollett declines to describe this apparatus.

22

The Austrian physician Vicenz Priessnitz is usually credited (or discredited) with making the water cure in the 1830s and 1840s what transcendental meditation was to the 1970s. The fashion for hydrotherapy in Europe, Britain, and the United States lasted more than half a century, probably because its pleasures, comforts, luxuries, and lack of medical discomfort so endeared it to patients and their companions.

23

At a time when about half of all surgical patients died either on the operating table or of complications afterward, physicians noted with interest (or on occasion indignation) that their clientele approached water cures with far less fear and repugnance than they did the measures of traditional “heroic medicine.” Priessnitz seems to have been the first to systematically exploit the commercial advantages of this feature of hydrotherapy.

Even in Priessnitz’s day there was an emphasis on women as patients. The Austrian technology, the first to be called “the douche,” was simply cold water impelled by gravity, but both earlier and later methods used hot or warm pumped water. Priessnitz’s cure, primitive as it was, was

all the rage; his caseload grew from 45 in 1829 to 1,400 ten years later, with many patients coming from Britain and remote parts of Europe.

24

The famous Father Sebastien Kneipp, another European hydropath, set great store by the use of pumped water aimed at the pelvis as a treatment for female complaints.

25

In Europe the physicians themselves might operate the douche apparatus, but in the United States this was considered professionally dubious, and therapeutic assistants were usually employed. J. A. Irwin, for example, writing in 1892, had considerable faith in hydrotherapy, both as a therapeutic measure and as a prescription most patients were willing to take. Bathing in mineral waters, he said, had the advantage of “stimulating qualities of the gas and minerals, which are appreciated by the skin as a kind of textural unctuosity.” He had reservations, however, about what he called “local irrigation” to relieve pelvic congestion in women, not because he thought it ineffective, but because he deemed it a threat to the decorum of the attending physician: patients stood in front of the doctor “receiving the column of water alternately, or as circumstances dictate, upon the spine and anterior surface of the body—a procedure somewhat startling to the Anglo-American sense of propriety, and scarcely in accord with our notions of professional dignity.”

26