The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction (19 page)

Read The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction Online

Authors: Rachel P. Maines

Tags: #Medical, #History, #Psychology, #Human Sexuality, #Science, #Social Science, #Women's Studies, #Technology & Engineering, #Electronics, #General

Chairs and trunk shakers, however, were of little value when local treatment was indicated. Joseph Mortimer Granville, father of the modern electromechanical vibrator, briefly summarizes the history of his invention and includes an illustration of a spring-driven wind-up “percuteur” (

fig. 18

).

116

A device called the “concussor,” available by 1898, was operated by foot power. Friedrich Bilz describes a device with a flywheel on a vertical stand, set in motion by a foot pedal (

fig. 19

). The business end is attached to “a so-called flexible axle (spiral spring) which can be easily twined in all directions.” The vibratode “can easily be taken off and replaced by one of a different shape; it is provided with a ball joint just beyond the excentric

[sic]

bend, on which variously shaped end pieces or instruments made of guttapercha or ebony are fitted.” Bilz notes with approval that “up to 3000 vibrations in a minute can be produced by rapid movement of the treadle by means of this machine, but an expert masseur cannot exceed 350 in the same length of time.”

117

The foot-pedal device he describes was clearly the low-budget model; Bilz’s own clinic had an electrically powered concussor. Mary Lydia H. A. Snow illustrates a different model of foot-powered vibrator, the “Victor,” in her 1904 book on vibratory treatment. Vibrators operated only with human energy proved fairly persistent in the market. Versions of them were sold to consumers in the United States after 1900, and Schall and Son, medical instrument makers of London and Glasgow, were still offering human-powered vibrators to physicians in 1925.

118

Snow also discusses and depicts water-powered and pneumatic vibrators, both of which were later to become consumer products.

F

IG

. 17. Jolting chair of the late nineteenth century. Photo courtesy of the Potsdam Public Museum.

The latter half of the nineteenth century was also, as we observed in

chapter 1

, the era of the steam-powered vibrator. The Swedish physical therapist Gustaf Zander’s European equipment for therapeutic exercise was the model for most spa machinery between 1860 and 1890; George Taylor improved on Zander’s ideas as well as those of other physical therapy equipment inventors by attaching his “Medical Rubbing Apparatus” to a stationary steam engine.

119

Taylor received patents in 1869, 1872, 1876, and 1882 for various kinds of massage machinery.

120

He especially recommended his devices for “pelvic hyperaemia” in women, noting that its “vibration may be compared to the blows of an infinitesimal hammer, under continuous and very rapid action.”

121

Of the hyperemia, he observed in his 1883

Health for Women

that “rapid vibratory motion applied to the affected part and to the surrounding region, produces absorption and the reduction of enlargement in a remarkable and … satisfactory degree.”

122

INSTRUMENTAL PRESTIGE

IN THE VIBRATORY OPERATING ROOM

Alphonso Rockwell reports that electromechanical vibrators were first used in medicine in 1878, at that nineteenth-century Mecca of physical therapies, the Salpêtrière in Paris. Significantly, their first use was on hysterical women.

123

Some controversy must have been associated with this practice, since the English physician and inventor Joseph Mortimer Granville, in his 1883 book on vibratory therapy, seems somewhat defensive about the issue:

I should here explain that, with a view to eliminate possible sources of error in the study of these phenomena, I have never yet percussed a female patient [with a vibrator], and have not founded any of my conclusions on the treatment of hysterical males. This is a matter of much moment in my judgment, and I am, therefore, careful to place the fact on record. I have avoided, and shall continue to avoid, the treatment of women by percussion, simply because I do not want to be hoodwinked, and help to mislead others, by the vagaries of the hysterical state or the characteristic phenomena of mimetic disease.

124

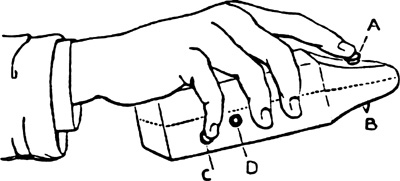

F

IG

. 18. Clockwork “percuteur,” from Joseph Mortimer Granville,

Nerve-Vibration and Excitation as Agents in the Treatment of Functional Disorders and Organic Disease

(London: J. and A. Churchill, 1883).

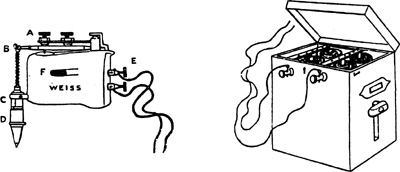

Mortimer Granville’s vibrator was powered by a large and heavy but allegedly portable battery and was equipped with a suitable array of vibratodes (

fig. 20

). It was manufactured to the physician’s specifications by Weiss, a reputable British maker of medical instruments.

125

Mortimer Granville asserts his priority in the invention, although Felix Henri Boudet claimed this honor for Vigouroux of the Salpêtrière.

As I described in

chapter 1

, dozens of models of vibrators were available by 1900, using a variety of power sources, many with impressive sets of attachments.

126

There was a brief rash of publications on the subject, advocating the use of “vibrotherapy” for a variety of ailments in women and men, including arthritis, constipation, amenorrhea, inflammations, and tumors.

127

At English and French hospitals in Serbia, some wounded World War I soldiers received vibrotherapy.

128

Physicians were advised to purchase professional-looking equipment, which could not be confused with consumer models. As Wallian observed in 1906 of the large number of vibrators available to physicians and the public: “The idea has been so vulgarized that the department stores and sporting goods houses are advertising ‘Health’ vibrators for home use.” Wallian has nothing but scorn for these devices; professional machines with sophisticated vibratodes such as the fluid cushion applicators of the “Physician’s Vibragenitant” were recommended (

fig. 21

).

129

Alfred Covey, author of

Profitable Office Specialities

, advised doctors in 1912 to invest in a good vibrator; prices ranged from $15 to $75.

130

In 1914 Wappler Electric offered an office model for $95 and a portable vibrator for $45; Manhattan Electrical Supply had a less costly line ranging from $25 to $40 at about the same time.

131

The elegant 125-pound Chattanooga Vibrator illustrated in

figure 4

(

chapter 1

) sold for $200 in 1904 and was positioned, in modern marketing parlance, as a professional medical instrument, not a “massage machine.” The company was careful to reassure prospective customers that “it is sold only to Physicians, and constructed for the express purpose of exciting the various organs of the body into activity through their central nerve supply.”

132

Catalog illustrations show treatment of both sexes, including treatment of males through the rectum (

fig. 22

). The company assured prospective purchasers that “this instrument will be found to be an invaluable aid to the physician in the treatment of all nervous diseases and female troubles,” later adding that “in cases where the patient is a woman and the nervousness is caused by either the ovaries or uterus, particular attention should be given to the lower part of the spine and also to the affected organs themselves.”

133

Franklin Gottschalk advised his fellow physicians in 1903 that the equipment should be carefully selected and maintained. He recommended that doctors acquire “at least two adjustable vibrators,” one for slow massages of “fifty to one hundred fifty periods per minute, giving muscles time to rest between each alternate contraction,” and another “for sedation, with a rapid vibration, adjustable for seven to nine thousand periods per minute.” Gottschalk thought his techniques especially useful in menopause.

134

In 1917 Anthony Matijaca commended vibrators to the readers of his

Principles of Electro-medicine, Electro-surgery and Radiology

as the only instrument of “mechano-therapy … which accomplishes something which cannot be accomplished by any other means.” Apparently losing control of his spelling as he warmed to his subject, he enthused, “No human hand is capable of cummunicating

[sic]

to the tissues such rapid, steady and prolonged vibrations, and certain kneading and percussion movements, as the vibrator.”

135

F

IG

. 19. Foot-powered vibrator with attachments, 1898.

F

IG

. 20. Mortimer Granville’s battery-powered vibrator, manufactured by Weiss, 1883.

The vibrator did not lack for theoreticians at the turn of the century. The most eloquent was Samuel Spencer Wallian, who wrote a series of articles for the

Medical Brief

in 1905, titled “The Undulatory Theory in Therapeutics.” In the first paper he informs readers that all life is based on vibration, a principle that was to be echoed in popular advertising for home vibrators. The “variation in vibratory velocity,” as he expressed it, produced various results in the great scheme of things: “A certain rate begets a

vermis

, another and higher rate produces a

viper

, a vertebrate, a

vestryman”

(emphasis in the original).

136