The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction (20 page)

Read The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction Online

Authors: Rachel P. Maines

Tags: #Medical, #History, #Psychology, #Human Sexuality, #Science, #Social Science, #Women's Studies, #Technology & Engineering, #Electronics, #General

His second paper concentrates on more practical issues, particularly the usefulness of vibrators in increasing the blood supply of the areas they were applied to. He argues that manual massage will do the same but “requires the expenditure of much time and strength on the part of the operator, and has practically no influence over deep-seated nerve or trophic centers.”

137

Some of the more metaphysical components of Wallian’s comments apparently resonated (as it were) with other philosophical notions then popular in the medical community. D. T. Smith, for example, published a book in 1912 called

Vibration and Life

, which explained “Sex among Corpuscles” and the “Possibility of Race Betterment,” among other topics related to the vibratory principles of the universe.

138

The vibrator’s English godfather Mortimer Granville expounded on its theoretical underpinnings in rhetoric that was self-consciously scientific and rational:

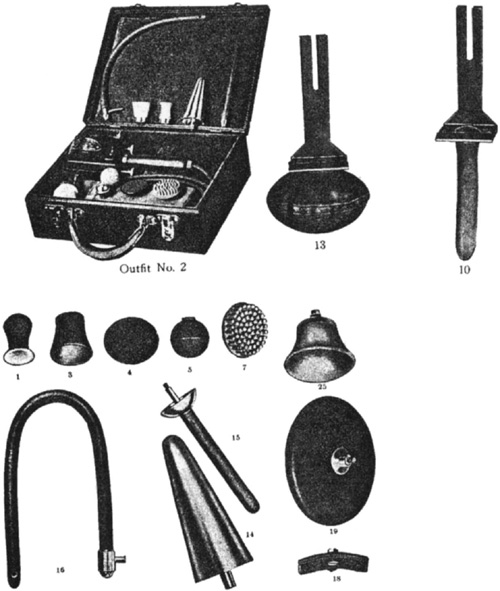

F

IG

. 21. Sam Gorman’s “Physician’s Vibragenitant,” with set of vibratodes.

As a necessary result of this state of matters, it must be possible to act on the nervous system by purely mechanical agents and influences, with the effect of interrupting, modifying, or altogether arresting organic vibrations, whether in afferent sensory or efferent motor nerves. These effects are capable of demonstration, producing changes in the rate and rhythm of nerve vibration precisely correspondent with those which would be effected in the vibration of unorganized substances by the operation of the same or similar agents working in like processes.

Despite his disclaimer about percussing women, Mortimer Granville tells us that this theoretical understanding was arrived at “in connection with the paroxysmal, or recurrent, pains accompanying the uterine contractions in the natural process of parturition.”

139

Physicians clearly had an interest in maintaining their professional dignity, even as they sought methods of treating such “elusive” disorders as hysteria with therapies that would attract repeat business to their examining rooms. In some locations they faced competition with beauty parlors, which began using vibrators early in the twentieth century, “because the sensations from their use are pleasing and the results instantaneous.”

140

Doctors were quite reasonably concerned, as a 1909 medical catalog expressed it, that “most of the vibrators sold by dealers and hawked about the country are mere trinkets which accomplish little more than titillation of the tissues.”

141

Titillation of the tissues, however, had an attraction for some patients that there was no compelling reason to resist.

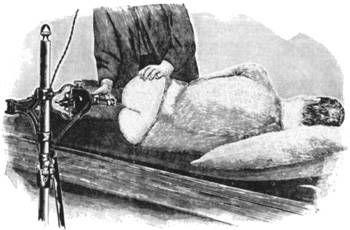

F

IG

. 22. The Chattanooga Vibrator in use on a male patient, about 1904.

CONSUMER PURCHASE OF VIBRATORS AFTER 1900

A number of incentives made it more appealing for consumers to purchase vibrators for self-treatment at home than to visit a doctor’s office regularly. The most obvious was cost: even a very good vibrator cost no more than four or five office visits, and it was available at all times, with no additional expenditure other than for electrical power. Consumers could use the device in privacy as often as they desired, and control it themselves, and the daring, knowledgeable, or shameless could involve their lovers or husbands. Water-powered vibrators, briefly popular in the first decades of this century, would have been poorly adapted to this purpose, but electromechanical devices, especially those with batteries, could be used anywhere. Increasing availability of home electricity must also have contributed to the popularity of the electromechanical vibrator.

The electrification of the home proceeded rapidly after the introduction of electric lights in 1876, and predictably, women were significant consumers of electrical appliances. The first home appliance to be electrified was the sewing machine in 1889, followed in the next ten years by the fan, the teakettle, the toaster, and the vibrator. The last preceded the electric vacuum cleaner by some nine years, the electric iron by ten, and the electric frying pan by more than a decade, possibly reflecting consumer priorities.

142

The earliest advertisement for a home vibrator I know of is for the “Vibratile,” which appeared in

McClure’s

in March 1899, offered as a cure for “Neuralgia, Headache, Wrinkles.”

143

Much less sophisticated than medical models offered at the same period, the Vibratile had only one vibratode, a coil of wire.

Massage had been a subject of public interest since the days of Mesmer,

and it lent itself to medical democratization at best and charlatanism at worst. Advertisements for home massage were common elements of the cornucopia of questionable products and services offered in popular publications in the early years of this century. The American College of Mechano-therapy, for example, announced to the readers of Men

and Women

in 1910, “Your Hands Properly Used are all You Need to Earn $3000 to $5000 a Year.”

144

Mechanical massage devices operated by hand cranks advertised in this way included the Lambert Snyder, which, according to an advertisement in 1907, “Relieves All Suffering. Cures Disease.” The device could “be placed in contact with any part of the body, and is capable of giving from 9,000 to 15,000 vibrations per minute.” The Lambert Snyder sent “the red blood rushing into the congested parts, removing disease and pain.”

145

The makers of the Bebout Vibrator, another hand-powered mechanical model, made their target market explicit in an ad in the

National Home Journal

in 1908: “

TO WOMEN

I address my message of health and beauty.” The item sold by mail for $5 and was advertised in terms reminiscent of Wallian’s alliterative rhapsodies on vibration in nature: “Gentle, soothing, invigorating and refreshing. Invented by a woman who knows a woman’s needs. All nature pulsates and vibrates with life.” Purchasers would find themselves in blissful harmony with the universe: “The most perfect woman is she whose blood pulses and oscillates in unison with the natural law of being.”

146

Down the left column of the page on which the Bebout appears are small advertisements for “hair stain,” nursing instruction by mail, furniture, broom clips, signet rings, ribbon, dropsy cures, postcards, poultry raising, matrimony, and rubber “Protectors” (“safe and sure, just the ‘article’ every woman wants”). Matchmaking was well represented, with three firms offering services, one of them offering “Pay when Married—New Plan.”

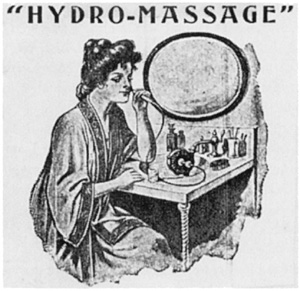

At this period, not all urban water systems were metered. Water customers paid a flat rate to connect with the main, a practice that cities soon abandoned on discovering that consumers used water at a rate that overburdened wastewater disposal systems. There was no economic disincentive to using one’s kitchen or bathroom faucet as a power source, and thus in the first two decades of the twentieth century there was a brief fashion for water-powered vibrators. On the embroidery page of the December 1906 issue of

Modern Women

the Warner Motor Company advertised a “Hydro-massage” machine operated from a kitchen or bathroom tap (

fig. 23

).

147

Amid ads for Palmolive soap, Onoto pens, cold cream, and lace, the May 1909 issue of

Woman’s Home Companion

had a small display advertisement for the Corbin Vacuo-masseur, reportedly “Sold by Druggists and Department Stores,” which apparently worked on hydraulic power as well.

148

The Blackstone Manufacturing Company offered a similar device ten years later; their ad in the April 1916 issue of

Hearst’s

is aimed at attracting sales agents who want to “Get started in an honest, clean, reliable, money-making business.”

149

Entrepreneurs who read

Hearst’s

were evidently more economically upscale than subscribers to

Modern Women

and

Woman’s Home Companion

; the other advertisements on the same page are for typewriters, law textbooks, a work on “The Power of Will,” corn pads, and manufactured homes. The

Bohemian

of December 1909 advertised an electric massage roller resembling the “electro-spatteur” sold earlier as a medical instrument.

150

F

IG

. 23. The Warner Motor Company’s water-powered “Hydro-massage,” 1906.

The most numerous advertisements for vibrators in the first three decades of this century, however, were for electromechanical vibrators of the type that are still manufactured and sold for home massage. Popular

magazines of the period accepted advertising for them but rarely mentioned them in editorial matter. Two exceptions are a one-liner in the June 1908

Review of Reviews

, which cautions readers against “imprudence” and “excess in action” when using vibrators, and Mildred Maddocks’s article about electricity in the July 1916

Good Housekeeping

, in which her evaluation of vibrators is limited to the observation that they are “soothing to the skin.”

151

These soothing effects figured prominently in the advertising copy for vibrators and in the instruction manuals that accompanied them. The American Vibrator Company of St. Louis, Missouri, which advertised in

Woman’s Home Companion

in 1906, stressed the superiority of its device over the unaided human hand:

Why has electrical massage taken the place of the manual, or Swedish method? Simply because it can be applied more rapidly, uniformly and deeply than by hand, and for as long a period as may be desired. The professional masseur can not only not reach as deeply as can mechanical vibration, but is manifestly unable to prolong his treatment for a sufficient length of time to accomplish the results attained by modern vibratory machinery, which never tires. The number and strength of the movements that can be applied by hand are extremely limited; the perfectly adjusted American Vibrator runs indefinitely and is susceptible of a variety and rapidity of movements utterly impossible of human attainment. (Emphasis in the original)

Women were advised that the “American Vibrator may be attached to any electric light socket, can be used by yourself in the privacy of dressing room or boudoir, and furnishes every woman with the very essence of perpetual youth.”

152

The Swedish Vibrator Company of Chicago sought sales agents for its product in the pages of

Modern Priscilla

of April 1913, extolling the device as “a machine that gives 30,000 thrilling, invigorating, penetrating, revitalizing vibrations per minute.” A brief demonstration would be sure to win customers’ approval, since they would have an “Irresistible desire to own it” after experiencing “the living, pulsing touch of its rhythmic vibratory motion.” On the same page is an advertisement for Professor Burns’s “Auto-Masseur … Both sexes,” which was apparently a kind of corset.

153

The Monarch Vibrator Company had a

small display ad in the February 1916 issue of

Hearst’s Magazine

, showing a young woman pressing the cup vibratode to her right temple and claiming that their instrument would “bring

SOCIAL AND BUSINESS SUCCESS

… If your circulation is poor, its smooth,

passive exercise

sends the blood coursing through veins and tissues. Wrinkles disappear, hollows fill up, weariness ceases, and you learn the real joy of living.”

154

In a contiguous advertisement, William Lee Howard’s book

Sex Problems in Worry and Work

promises to answer questions such as, “Is Chastity Consistent with Health?” and to elucidate “The Sexual Problem of the Neurasthenic.”

155

General Electric featured a vibrator in a full-page advertisement for “The Home Electrical” between 1915 and 1917.

156