The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction (23 page)

Read The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction Online

Authors: Rachel P. Maines

Tags: #Medical, #History, #Psychology, #Human Sexuality, #Science, #Social Science, #Women's Studies, #Technology & Engineering, #Electronics, #General

In our own culture there have been, and remain, powerful means of negatively reinforcing women’s demands for orgasmic mutuality. A woman’s admitting that coitus does not by itself ring her chimes is in some quarters still a confession of defect. In addition, Western men are expected to be born knowing how to satisfy women in much the same way as women are assumed to be born knowing how to cook. Men have in the past even been held responsible for women’s sexuality; Frank Caprio told young husbands in 1952 that “the sexual awakening of the wife [was their] responsibility.”

11

In light of these impossible standards, men have not traditionally been interested in truthful (and perhaps unflattering) answers to their questions about female satisfaction; even where such answers have been provided, a man has had the option of blaming the woman for her (and thus his) failure.

12

Medical advice writers like Caprio have traditionally provided such encouragement as the assertion that women’s “fixation of the sexual instinct” on the clitoris is the result of “excessive manipulation.” Most of the rest of Caprio’s book is about the problem of female “frigidity” caused by such pathological “fixations.”

13

Few women are prepared to expose their intimate behavior to this kind of socially supported criticism. For most women struggling with more pressing problems of economic survival and family harmony, the cost of fighting the androcentric norm would almost certainly have seemed greater than the very slender possibility of ultimate reward.

14

In 1848 the French author Auguste Debay wrote that women should fake orgasm because “man likes to have his happiness shared.”

15

He was neither the first nor the last to take this position. Celia Roberts and her coauthors, studying the faking of orgasm in a sample of college women, found that “in almost every woman’s interview these practices were

mentioned as something they did, at least some of the time.” Male interviewees were nearly all certain that no woman had ever faked orgasm with them, an observation about which the authors remark, “Clearly, the refined performances which women are giving are extremely convincing.” Female subjects explained their behavior by referring to a greater interest in preserving the stability of their relationships than in reaching orgasm on every occasion of intercourse.

16

Despite the systematic perpetuation of ignorance and misunderstanding—by women as well as men—most heterosexual men have looked to the female orgasm to reinforce their self-respect as sexual beings. Michael Segell says that “according to one study, one of the four utilitarian aspects of the female orgasm is the boost it gives men’s egos.”

17

A thirty-three-year-old male interviewed by

Glamour

advised his fellows, “When you find a woman who can come to orgasm through penetration and not just clitoral stimulation, keep her. She’s a rare and wondrous thing.”

18

Clearly, for this man no other female characteristics matter. Inevitably, such pressures could push women in only one direction: toward pretending to reach orgasm when it did not occur.

19

The readers of

Mademoiselle

reported in the early 1990s that 69 percent of them had faked orgasm at least once.

20

Carol Tavris and Susan Sadd, reporting the results of a survey in 1977, include two quotations from their respondents:

I have conducted my own little survey and I do not have one friend or acquaintance who has ever had a “real” orgasm through intercourse—only through clitoral stimulation. However, try convincing a

man

you don’t have orgasms his way. He won’t believe you. But challenging him that way can get quite interesting! I have never had an orgasm during sexual intercourse. To have an orgasm, I must have cunnilingus or manual clitoral stimulation. I know of women today who are faking orgasm during intercourse because they are too embarrassed to tell their husbands or lovers that no matter how long they keep their erection, they just can’t make her have orgasm.

21

Robert Francoeur says of orgasmic pressures on women in heterosexual relationships that “women are much more likely to pretend to have had an orgasm when they haven’t” and points out that such pretense often results in “real problems of resentment and even anger with the partner.”

22

Not all women agree. Stephanie Alexander, writing in

Cosmopolitan

in 1995, asserts that faking orgasm is “just a matter of expediency, not to mention common courtesy.” Regarding the cost of trying to explain why one has not reached orgasm, she asks, “When you have to get up for work the next morning, who has two spare hours to make him feel better about not making you feel great?”

23

In effect, these accounts suggest that half of the heterosexual couple is expected to sacrifice orgasmic mutuality in order to avoid the inevitable stresses on the relationship caused by rocking the androcentric boat. As a culture, we must value the androcentric norm very highly even to suggest that maintaining it is worth such a price.

In the second half of this century, the work of Masters and Johnson and their followers has made yet another sacrifice to the androcentric model of sexuality: the objectivity of scientific thinking. When these researchers chose their sample, they selected only women who regularly reached orgasm in coitus—an error, it is worth noting, not made by their predecessor Alfred Kinsey. That these women were a minority was already known at the time Masters and Johnson made their study, but it had apparently been decided that these outliers represented normality. It is generally held to be a principle of the scientific use of statistics that the experience of the majority represents the norm; that is, the normal range is the part of the curve directly under the bell on a line graph. Were it not for the very strong and apparently widespread bias in the direction of the androcentric norm, Masters and Johnson would have been the laughingstock of the medical community. This did not occur. Not until Shere Hite attacked the Masters and Johnson results in 1976 did questions begin to be raised about their methods of selection and interpretation. Errors of this kind not only have prevented us from understanding female orgasm as a physiological phenomenon but have diverted us from fully recognizing how individual and idiosyncratic sexual pleasure is for both sexes.

The reactions (and overreactions) to Hite’s own study also reveal much about how vigorously we have been willing to defend the androcentric model. Her work was severely criticized on the grounds that participants were self-selected, a problem that had arisen not only with the Kinsey and the Masters and Johnson samples but with nearly every other survey of sexual practices in this country in the past hundred years. As a purely practical matter, people cannot be compelled to respond honestly to questions about intimate behavior; researchers have no choice but to rely on data whose representativeness is and must remain in doubt. In Hite’s case, however, there were far more attempts to make this difficulty a fatal flaw than were made concerning her predecessors’ work. Excuses of the most flimsy and embarrassingly male-centered kind were offered for rejecting Hite’s hypothesis outright. In 1986, for example, the Hite reports were the subject of a session on the history of sexuality by the Organization of American Historians. One of the male participants criticized Hite’s attention to the issue of orgasm in heterosexual relationships as “somewhat mechanistic.” This is a very glib criticism from the side of such relationships that is having most of the orgasms.

24

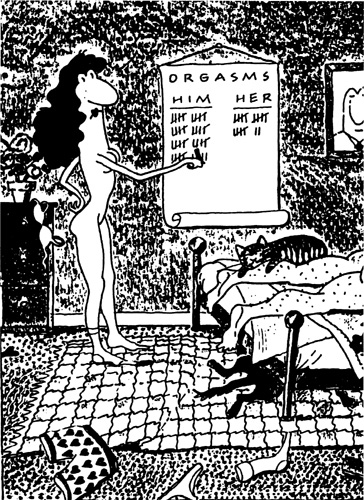

F

IG

. 26. Cartoon representing the dilemma of orgasmic mutuality in heterosexual relationships. The caption reads, “Wake up—honey … I think we need to have a talk.” By Elizabeth W. Stanley and J. Blumner for the Maine Line Company, ca. 1986.

THE VIBRATOR AS TECHNOLOGY AND TOTEM

As we have seen, the medicalizing of female orgasm in Western culture has been one means of protecting our comfortable illusions about coitus. The vibrator and its predecessor technologies—particularly manual and hydriatic massage—made it easy for physicians to provide the relief that was not otherwise accessible to many women. The vibrator was convenient, portable, and fast and thus enjoyed a considerable, if brief, popularity as a medical instrument before its discovery by consumers and by the makers of erotic films. The ultimate difficulty of the vibrator, from the point of view of the medical profession, was that it was so convenient and easy to use that it rendered unnecessary any medical intervention in the process of producing female orgasm. Hydriatic equipment and expensive office vibrators like the Chattanooga at least kept massage innovation in the hands of medical professionals; once the vibrator became a relatively lightweight and inexpensive device that could be operated by water or electricity in the home, it became a “personal care appliance” and not a medical instrument.

In the second half of this century the vibrator has become an overtly sexual device. Interestingly, when such devices appear in erotic films, it is rarely the true vibrator that is portrayed; what is seen is the reassuringly phallus-shaped vibrating dildo, with its suggestion that the machine is really only a substitute for a penis.

25

Edward Kelly, writing of

vibrating dildos in 1974, avers hopefully that “without doubt, except in cases of lesbianism, the haunting vision of some imagined male broods over each use of any dildo.”

26

For most women, however, these underpowered battery-operated toys are more visually than physiologically stimulating; it is the AC-powered vibrator with at least one working surface at a right angle to the handle that is best designed for application to the clitoral area.

Beyond the functional role of the vibrator for women consumers and their sexual partners, the device has taken on a totemic quality in American culture. Some male authors have pointed out that the vibrator makes an excellent addition to a couple’s armamentarium of sex toys because it produces orgasm in women (and some men) with very little effort or skill. It has also become a favorite of sex therapists for the same reason—even women with very high orgasmic thresholds will usually respond eventually to vibratory massage. Those with lower thresholds can use the machine to explore their full orgasmic potential with very little fatigue. These two aspects of the vibrator have almost inevitably made it a focus of the kind of male fears played on by such jokes as, “When did God make men? When she realized that vibrators couldn’t dance.”

27

Since the Industrial Revolution, as Michael Adas has pointed out, men have tended to measure themselves against machines, a comparison virtually guaranteed to produce anxiety.

28

In the case of vibrators, this tension is especially poignant and has sometimes led men to resent the device. As one of the

Redbook

survey’s respondents said of her adventures with her vibrator, “My husband doesn’t know. If he did, I think he’d throw it out!”

29

The late Melvin Kranzberg has been widely quoted in the observation that “technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.”

30

The vibrator and its predecessors, like all technologies, tell us much about the societies that produced and used them. The device remains with us, praised by some and reviled by others, neither good, bad, nor neutral, a controversial focus of debate about female sexuality. Some of this controversy, as we have seen, has very old roots in Western culture, occupying the space in which sexuality, morality, and medicine interact and serving as an outer line of defense of the androcentric model of orgasmic mutuality in coitus. The rifts in this ancient wall continue to be patched with exhortations to women to avoid challenging the norm even if it

means faking orgasm and sacrificing honesty in their intimate relationships with men. In the past we have been willing to pay this price; whether we should continue to do so is a question for individuals, not historians, to decide.