The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction (17 page)

Read The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction Online

Authors: Rachel P. Maines

Tags: #Medical, #History, #Psychology, #Human Sexuality, #Science, #Social Science, #Women's Studies, #Technology & Engineering, #Electronics, #General

The reported enthusiasm of women for the douche is not surprising. A jet of pumped water aimed at the male genitalia is more likely to produce pain than pleasure, but the use of water as a female masturbatory method is well documented, although in this century it is apparently employed only by a minority. Shere Hite reported in 1976 that about 2 percent of her respondents masturbated with water, using either the direct force of the water from the tap or hand-held shower hoses.

57

Linda Wolfe’s

Cosmo Report

of 1981 also mentioned this technique.

58

This method of masturbation raises questions about the early popularity of such hoses at the beginning of this century, when bathtubs first became common in urban households.

59

Donald Greydanus, who cites W. R. Miller and H. I. Lief’s estimates that masturbation is practiced by 97 percent of males and 78 percent of females, mentions “tap water masturbation” but provides no further data on its incidence.

60

In a popular anthology of women’s fantasies published in 1975, the speed and efficacy with which a jet of pumped water produces orgasm in women is noted in a chapter called “Playtime in the Pool.”

61

Inspired by a mention of masturbation with water in the first edition of

Our Bodies, Our Selves

in 1970, Eugene Halpert reported on this practice to the American Psychoanalytic Association in 1973, using three case studies of his own female patients. A staunch Freudian, Halpert makes it clear from the beginning that he considers this behavior aberrant: in each of the three cases, he asserts that the patient “was frigid” in the context of intercourse. After the obligatory review of the literature and a brief discussion of male masturbation with water, he describes the phenomenon reported by his three patients: “They all used the identical method, lying on their backs in the tub and positioning themselves so that the water from the faucet could be run on their genitals.” Adjustments in the temperature and flow of water onto the clitoris were usually necessary, after which orgasm reliably occurred in short order. Halpert, after dutifully describing what he takes to be relevant dreams, fantasies, and childhood experiences of the three women, concludes that these women are fulfilling fantasies to the effect that “I have my father’s penis and can urinate/ejaculate like a man, and I am able to urinate and destroy/castrate with my powerful stream in revenge for castration.”

62

Apparently, to a Freudian the production of orgasm in this manner required an elaborate explanation beyond the straightforward desire for pleasure and sexual release.

63

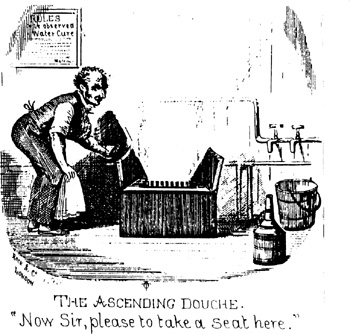

F

IG

. 12. British male reaction to the ascending douche, from Joseph Buckley,

Recollections of the Late John Smedley and the Water Cure

(1888; Matlock, England: Arkwright Society, 1973).

ELECTROTHERAPEUTICS

Electrotherapeutic devices were an invention of the eighteenth century, beginning with electrostatic generators that transferred static electricity to the hands and progressing, in the nineteenth century, to various kinds of direct-current devices and electrets.

64

The latter, such as “electric” hairbrushes and corsets, lacked any power source; their presumed efficacy consisted in the electrical charging of the materials during their manufacture.

65

In the mid-nineteenth century, electric current from batteries, including so-called “vibrators” (actually inductive devices that rhythmically interrupted the current), were used to control dental pain.

66

Audrey Davis says that subsequent developments included “a spectacular range of devices … for applying heat, electricity, water, x-rays, and various motions and vibrations to the body in the period beginning at the end of the nineteenth century.”

67

In the second half of the nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth, there was considerable medical and scientific interest in electrolytes, human skin conductivity, and the effects of electrical stimulation on the health of plants and animals.

68

Some doctors thought that electrical contraction of muscles could be useful as a substitute for exercise.

69

Of particular interest to physicians was the perceived potential of electrotherapeutic treatment of impotence and “sexual debility” in men, both thought to be caused at least in part by masturbation.

70

Popular medical literature and advertising encouraged men’s anxiety about losing virility to the solitary vice, and thousands of electrical devices were sold directly to consumers on the strength of their alleged ability to restore masculine powers; some physicians specialized in providing electrotherapeutic services.

71

Richard von Krafft-Ebing mentions these devices briefly, citing a case of a young man who masturbated with a battery. Arousal to orgasm in this fashion would certainly have convinced purchasers that their male powers were in a healthy condition.

72

Historian of medicine David Reynolds remarks on the phenomenon:

It was perhaps inevitable that finally, at about the time of Freud’s initial papers on the sexual bases of neurosis, Rousell should report “It is especially in the genital organs that electricity is truly marvelous. Impotence disappears, strength and desire of youth return, and the man, old before his time, whether by excesses or privations, with the aid of electric fustigation, can become fifteen years younger.” Electrotherapeutic currents were also recommended for nymphomania. Presumably the treatment for nymphomania differed from that for impotency—perhaps a reversal of polarity. The responsibility of the nineteenth century physician in treating impotency and nymphomania with electricity was awesome. A mix-up in the leads could result in personal tragedy in one patient—a social menace in another.

73

William Snowdon Hedley wrote in 1892 about a set of therapeutic procedures known as “hydro-electrization,” which included an “electric douche” applied with saline “water electrodes.” The method was recommended as a stimulant for “heightening cutaneous sensibility and quickening motor excitability.”

74

In 1903 the International Correspondence Schools’

System of Electrotherapeutics

recommended an electric douche regimen that combined electrical currents with hydrotherapeutic and sometimes vibratory or manual massage.

75

By 1918 manufacturers of physical therapy equipment, like Kellogg in Battle Creek, Michigan, were producing apparatus that would provide alternating current through a hydroelectric bath, utilizing a “motor-operated magneto.”

76

As Reynolds indicates, electrotherapeutic methods were used in women’s disorders as well as men’s, including not only the nymphomania he mentions but also dysmenorrhea, infertility, “frigidity,” and that turn-of-the-century bane of the educated classes, neurasthenia.

77

Richard Cowen wrote in 1900 that electricity worked well in dysmenorrhea when combined with local massage to “stimulate the circulation in the pelvic organs, to get rid of the congestion and the hyperaemia.”

78

Herman Hoyd endorsed battery application of “faradic current” by the patient herself to improve uterine and vaginal muscle tone.

79

A. Lapthorn Smith, writing in Horatio Bigelow’s 1894 textbook of electrotherapeutics, advocated the use of battery faradization in amenorrhea and female infertility, despite the technical difficulties of keeping the batteries filled, charged, and ready for use. Bigelow had “always been reluctant to apply local treatment to unmarried women” but considered it appropriate for wives. He could, he said, “testify positively” to visible results in amenorrhea and infertility, “but with regard to the development of any passion I cannot speak very decidedly, as it is difficult to induce women to speak much about it,” although in a few cases he felt he had “reason to believe that sexual feeling actually was experienced after many years of married life without it.”

80

F

IG

. 13. Vaginal electrode, from Franklin Benjamin Gottschalk,

Practical Electro-therapeutics, with a Special Section on Vibratory Stimulation

(Hammond, Ind.: F.S. Betz, 1903).

Franklin H. Martin wrote in 1892 about electrical treatment of “nervous inefficiency” in women, brought on by childbearing, “excessive cohabitation, or undue treatment of a local variety.” In his view the “nervous perversion” he saw in his patients was more often due to “too much studying” and “the worries of motherhood” than to the masturbation his colleagues suspected as the etiology.

81

Martin described his procedure as “a process of kneading or petrisage … performed over the surface of the body, dwelling particularly on the motor points of the muscles, in which the current is simply strong enough to produce an agreeable prickling sensation.”

82

Havelock Ellis, writing between 1897 and 1910 on “autoerotism,” seems convinced that mild electric shocks produce sexual arousal in women. In his discussion of what he calls

rin-no-tama

, what we would now call benwa balls for vaginal insertion, he says that the movement of such devices “and the resulting vibration produces a prolonged voluptuous titillation, a gentle shock as from a weak electric inductive apparatus,”

83

throwing possible light on the use of electricity to awaken or reawaken desire.

John Harvey Kellogg, who was a great believer in the benefits of pelvic muscle contractions for treating neurasthenic women, told attendees of the International Electrical Congress in 1904 that galvanic electrical methods achieved spectacular results when applied to the genital area:

The contraction is spasmodic rather than tetanic in character, as when the faradic current is employed. By proper adjustment of the current, strong muscular contractions may be induced without producing the slightest sensation on the skin, and without any pain sensation whatever. With one electrode placed in the rectum or the vagina, and the other upon the abdomen, strong contractions of the abdominal muscles may be produced, and even of the muscles of the upper thigh, without any sensation other than that of motion. I have frequently seen patients, while receiving the current in this manner, shaking so vigorously under its influence that the office table was made to tremble quite violently with the movement.

84

Electrotherapeutic devices sold to consumers for self-treatment seem to have enjoyed significant popularity between about 1880 and the late 1910s (figs. 13 and 14). One of these was the Butler Electro-massage Machine of 1888, pictured in

figure 2

(

chapter 1

), which combined roller massage with a mild electrical shock. For uterine diseases, the roller was to be used “over lower abdomen, from 10 to 15 minutes. Change the treatment every other day, using the vaginal sponge-electrode, and applying roller over lower abdomen ten minutes, and lower spine five minutes.” Butler expressed his conviction that three-quarters of the female population suffered from conditions for which his massage device was indicated. Among the many testimonials that appear in his advertising is one from a grateful husband, who reports that his wife treated herself for “female weakness, and general debility of the system, with the most gratifying results.”

85