The Tenth Saint (31 page)

She retrieved a spiral-bound notebook from her handbag and gave it to Sarah.

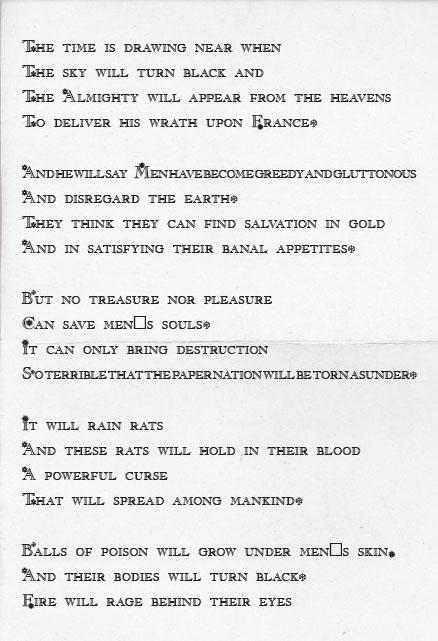

Sarah read the title on the cover page. “Divination. By Bernard de Bontecou.”

“Naturally, this is a copy,” Marie-Laure said. “The original was found in the Manoir de Vincennes, a family estate in the outskirts of Paris that has since been razed. In the late fourteen hundreds, a relative by the name of Lady Antoinette Colbert inherited the manor and set about restoring it. In the process, she found these handwritten manuscripts hidden behind the bricks of a fireplace. She was struck by their contents and proceeded to have them published at her own expense. The book circulated briefly until the church found out about it and deemed it heresy. They tracked down and burned every copy except the one Antoinette managed to smuggle out of the country to London. It is now in our family archives.” She again reached inside her handbag.

Sarah looked around the courtyard. Nothing stirred. The building was illuminated with the faint pewter light of the waxing moon. A light breeze whistled over the rooftops. Marie-Laure handed her a small reading light, and she looked through the pages carefully. The first chapter was an entry about the Black Death, written in the future tense and titled “Man’s Divine Judgment.”

Sarah felt a chill rake her skin. “I don’t understand. When was this written?”

“In 1345. Three years before the plague struck France.”

“How could he have known?”

“At first I thought he had witnessed something like the plague during his trips to Italy and perhaps had guessed the disease would inevitably reach France. But as I read more of his writings, it became clear he had a different kind of foresight. Turn to page one hundred forty-six.”

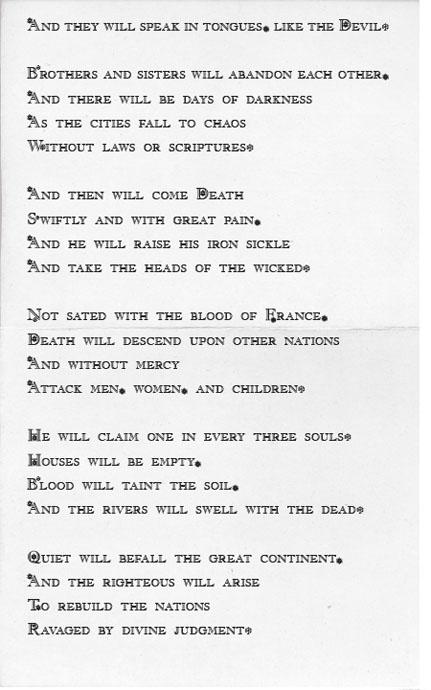

Sarah did. The chapter titled “The Great Power” was an account of modern America. She read, stunned at the degree of accuracy, especially in this passage:

Marie-Laure showed her other chapters—”War” about the Holocaust and the Second World War and “The Two Towers” about the September eleventh attacks.

Either this guy was truly prescient, or all of this was a forgery.

“I realize you are a scientist,” the Frenchwoman said, “and as such you require proof. Our family archives will be opened to you should you wish it.”

Sarah was flattered but puzzled. “Why would I want access? What is all this supposed to mean to me?”

Marie-Laure turned to a page near the end of the book. “I thought you might find this interesting.”

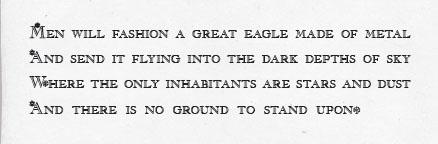

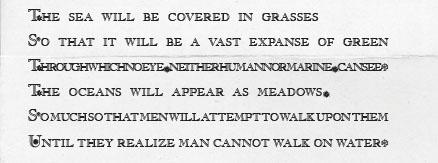

Sarah read the final and untitled passage, which described great fires and all-consuming smoke.

“Does it sound familiar?” Marie-Laure asked.

Sarah shook her head, stunned at the similarity between these writings and the words of Gabriel. Then she recalled Marie-Laure’s message:

I know who the second was.

“Are you saying Bernard was one of the three prophets?”

“No. But I believe his lover was.”

“His lover.”

“All we know of her is her name: Calcedony. Bernard never spoke of her in his writings. The church has no record of a marriage. There were no children, apparently. It’s as if she never existed.”

“Then how can you be sure she did?”

”We have a letter, written by Calcedony to Bernard as she awaited her execution. She was apparently arrested as a heretic and imprisoned under the authority of King Philippe VI and was hanged forty-eight hours later. She must have written this letter when she knew there was no hope for her, for what it contains …” Marie-Laure fell silent. “Sarah, no living person except me knows about this letter. It has been a dark secret in our family for centuries. Only one person at a time has been burdened with the knowledge of it, passing the torch only at the time of death. No one has really known what to make of it. Some have believed; others, no. For my part, I thought it was the desperate attempt of a tragic woman to save her hide by claiming she was someone she could not possibly have been. Or maybe it was merely a hallucination brought on by the lack of food and water, torture, or perhaps the early stages of plague. Anything but the truth. But now, after reading about your discovery … I fear the truth is exactly what this letter contains.”

“Why fear the truth?”

“When you read the letter, you will know. I will say no more. You must judge for yourself whether this is truth or rubbish. Whether there is any connection between your Gabriel and Calcedony.”

Marie-Laure reached inside her manteau and pulled out a bundle of papers rolled into a scroll. “I hope it is the puzzle piece you have been seeking—for the sake of all of us.”

Twenty-Two

I

t was the eve of the twenty-third day of battle. A moonless night had fallen swiftly on the barren lands of Meroe, blanketing the sandy wasteland with darkness. The acrid scent of stagnant blood and rotting flesh choked Gabriel’s throat, and he fought back the instinct to gag. Death was everywhere, not least of all in the infirmary tent, more akin to a slaughterhouse than a place of healing. He made his way past the bloodied bodies that lay moaning in the darkness. He knew many wouldn’t make it through the night.

A soldier moaned like a woman in childbirth and pleaded, “Let me die.”

Gabriel checked his abdomen, where the sword had ripped the flesh from the sternum to the navel, to see if the bleeding had stopped. Two days earlier he had sewn the laceration with cotton thread spun by the elder women of the court and an iron needle, which he had designed and Hallas had forged before he rode to Meroe. That had stopped the bleeding, but now the wound was suppurating, the skin swollen like a milking goat’s udder. The infection was too advanced.

“It will be better in the morning, friend,” Gabriel lied to comfort the soldier in his last hours. “Get some sleep.”

He moved on to another victim, a stoic boy who was too young to be drafted into battle but had insisted on volunteering. He was thirteen, fourteen at most, but had the serene countenance of a man who had lived many lifetimes.

“How’s that arm?” Gabriel removed the blood-soaked bandage to find exposed, weeping flesh. The boy’s forearm had been sliced off by a particularly sinister blade, and the bleeding would not relent in spite of the stitches Gabriel had put in earlier. He smeared the wound with fresh horse manure, which he’d used before to curb hemorrhage. It was risky—the bacteria in the manure could do more harm than good—so he gave the young soldier a myrrh broth to prevent infection.

“Tomorrow I’ll be ready to fight,” the boy said, “with thanks to you.”

“I haven’t done anything. I am only a simple man trying to help.”

“That’s not what the men say. They say you are a healer with divine powers. A holy man sent by the Lord of heaven to protect us from evil. They say you came down from the heavens to help us win this war and unify the lands of the Nile into one great, impenetrable empire.”

Gabriel smiled and squeezed the boy’s hand. “You should rest. Big day tomorrow.”

A few sleepless hours later, the dawn washed the sky in streaks of scarlet and saffron. It was an ominous beauty, heralding the advent of fresh bloodshed. Outside the tent, the troops were moving at a panicked pace, as if some malevolent force lurked beneath the sands. Gabriel approached a lieutenant readying his horse for battle.

“Why are the men so restless, friend?”

The soldier, a compact and muscular African with skin the color of tar, bowed his head: the standard greeting toward men of God. “This day will bring evil that we have never known. The men fear for their lives.”

“Why is today different from any other day?”

“Today we will be challenged by a regiment fiercer than any we have met thus far. Meroe has called for aid, and thousands of Nobatae are riding south as we speak. The horse and camel warriors. The Meroan military elite. Some are here already, fighting our troops at the northern edge of the battlefield.”

”Who are these Nobatae? Why fear them so?”

“These warriors know not God nor king nor country. The Romans themselves trained the Nobatae and bestowed upon them a cache of weapons far more advanced than our own. But the Nobatae were not to be trusted. They turned against the Romans and proclaimed their independence. They rode in the tribal lands, unchecked and untamed. Soon they forged a partnership with the most wretched and ruthless tribe in all the Nile. The headless warriors we know as the Blemmyes.”

Gabriel could see the men feared the legend more than the enemy itself. “Headless warriors exist only in myth. Surely this foe is not as bad as you think it to be.”

The soldier shuddered. “They are heathens. They kill everything and everyone crossing their path: men, women, children, horses, livestock. They are said to be undefeated in battle.”