The Third Reich at War (61 page)

The mobilization of all camp labour at first for military tasks (to raise armaments production) and later for peace-time building programmes is becoming increasingly important. This realization demands action which will permit a gradual transformation of the concentration camps from their old one-sided political form into an organization suited to economic requirements.

122

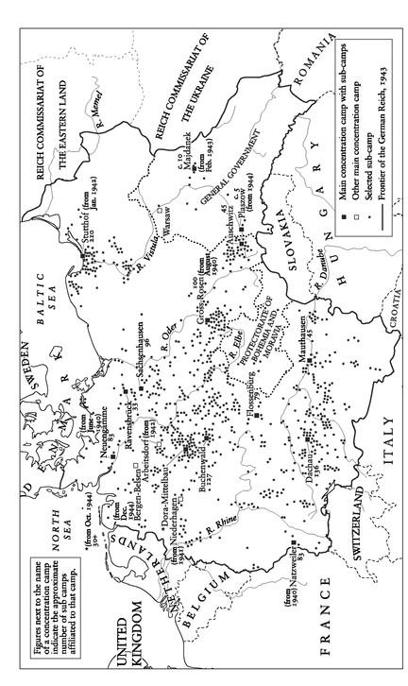

13. Concentration Camps and Satellite, 1939-45

Himmler was in broad agreement with this radical change, though he continued to insist that the camps should carry out political re-education, ‘otherwise the suspicion might gain ground that we arrest people, or if they have been arrested keep them locked up, in order to have workers’.

123

The labour was provided under broadly the same arrangements as obtained at Monowitz: the SS received payment for it, and in return supervised and guarded the labour detachments, made sure they worked hard and supplied them with clothes, food, accommodation and medical assistance. Himmler ordered that skilled workers in the camp population should be identified, and that others where appropriate should receive training. The bulk of them were used in construction projects, for heavy and relatively unskilled physical labour, but where they did possess expertise, Himmler intended that it should be exploited. Ever since 1933, many camp inmates had been marched out on work duties on a daily basis, but such was the scale of the system’s expansion from this point onwards that it soon became necessary to establish sub-camps near workplaces more than a day’s march from the main camp. By August 1943 there were 224,000 prisoners in the camps; the largest was the complex of three camps in Auschwitz, with 74,000, then Sachsenhausen, with 26,000, and Buchenwald, with 17,000. By April 1944 the inmates were housed in twenty camps and 165 sub-camps. By August 1944 the number of inmates had climbed to nearly 525,000. Increasingly, too, forced labourers in the occupied territories were transferred to the Reich, so that on January 1945 there were nearly 715,000 inmates, including more than 202,000 women.

124

By this stage, the proliferation of sub-camps, many of them quite small, had reached such dimensions that there was scarcely a town in the Reich that did not have concentration camp prisoners working in or near it. Neuengamme, for example, had no fewer than eighty-three sub-camps, including one on Alderney, in the Channel Islands. Auschwitz had forty-five. Some of these were very small, for example at Kattowitz, where ten prisoners from Auschwitz were engaged through 1944 on the construction of air-raid shelters and barracks for the Gestapo. Others were attached to major industrial enterprises, such as the anti-aircraft factory run by the Rheinmetall-Borsig company at the Lauraḧtte, where roughly 900 prisoners were working at the end of 1944 alongside 850 forced labourers and 650 Germans. Many of the prisoners were picked for their skill and qualifications, and these were relatively well treated; others worked in the kitchens, provided clerical services, or did unskilled labour loading and unloading products and equipment. The camp where they lived was run by Walter Quakernack, a guard seconded from the main camp at Auschwitz and known for his brutality; he was executed for his crimes by the British in 1946.

125

But this situation soon changed when the SS lost control over the distribution and employment of camp inmates, which was finally taken over by the Armaments Ministry in October 1944. In the final months of the war, the SS was reduced, in effect, to the role of simply providing ‘security’ for the prisoners’ employers.

126

A vast range of German arms companies made use of camp labour. Such was the demand from business, indeed, that in contravention of the most basic ideological tenets of the SS and the camp administrations, even Jewish prisoners were commandeered if they had the right skills and qualifications.

127

Businesses were indifferent to the prisoners’ welfare, and the SS continued to treat them in the same way as in the camps, so that malnourishment, overwork, physical stress and not least the continual violence of the guards took their toll. At the Volkswagen factory in Wolfsburg, 7,000 camp inmates were employed from April 1944 onwards, mostly on construction work; the miserable conditions under which they lived were of little concern to the company management, and the SS continued to prioritize the suppression of the prisoners’ individuality and group cohesion over their maintenance as effective workers.

128

Prisoners were drafted in to the Blohm and Voss shipyards in Hamburg, where the SS set up another sub-camp. Here too the economic interests of the company conflicted with the repressive zeal of the SS.

129

At the Daimler-Benz factory in Genshagen, 180 inmates from Sachsenhausen were put to work from January 1943, to be joined by thousands more from Dachau and other camps in a variety of plants. The deployment of camp labour was the motor driving the creation of sub-camps across the country, reflecting in its turn the increasing dispersal of arms production over many different sites, some underground, others in the countryside, in an effort to evade the attention of Allied bombing raids. Business needed a quick injection of labour to build the new facilities, and the SS was more than willing to supply it.

130

Deaths in forced labour camps were common, and conditions were terrible. Everywhere, prisoners who were too weak or too ill to work were killed by shooting or, in some cases, gassing. Unlike the other camps, the Auschwitz complex continued to the end to serve the dual function of labour and extermination camp, and mass gassing facilities elsewhere only found relatively restricted use in comparison, as at Sachsenhausen or Mauthausen. However, SS camp doctors in general were given instructions to kill inmates who were too ill or too weak to work, by giving them lethal injections of phenol. The cause of death in such cases was given as typhus or some similar ailment.

131

On 16 December 1942 the deputy commandant of Auschwitz, Hans Aumeier, was recorded as telling the SS officer in charge of deportations from Zamość:

Only able-bodied Poles should be sent in order to avoid as far as possible any useless burden on the camp and the transport system. Mentally deficient persons, idiots, cripples, and the sick must be removed as quickly as possible by liquidation so as to lighten the load on the camp. Appropriate action is, however, complicated by the instruction of the Reich Security Head Office that, unlike Jews, Poles must die a natural death.

132

Thus, in effect, Aumeier was saying that only when Poles were killed did the records have to be falsified to record death by natural causes. Death rates were indeed high. No fewer than 57,000 out of an average total of 95,000 prisoners died in the second half of 1942 alone, a mortality rate of 60 per cent. In some camps, notably Mauthausen, where ‘asocial’ and criminally convicted Germans were sent for ‘extermination through labour’, death rates were even higher. In January 1943 Glücks ordered camp commandants ‘to make every effort to reduce the mortality figure’, thus ‘preserving the prisoners’ capacity for work’. Death rates did indeed decline somewhat after this. Nevertheless, a further 60,000 prisoners died in the camps between January and August 1943 from disease, malnutrition and ill-treatment or murder by the SS.

133

A continual tension existed between the SS, which was unable to abandon the ingrained concept of the camps as instruments of punishment and racial and political oppression, and employers, who saw them as sources of cheap labour; it was never satisfactorily resolved.

134

How far did business profit from the employment of forced and prisoner labour? Certainly it was indeed cheap. A Soviet prisoner of war, for instance, cost less than half to employ than a German worker did. Up to 1943 German business most probably gained financially from using foreign workers. But their productivity was low, particularly if they were prisoners of war. In 1943/4, for example, the productivity of prisoners of war in the coalmines was only half that of Flemish workers.

135

But foreign labour was increasingly used on construction projects that did not yield significant profits before the war came to an end. The giant chemicals plant at Auschwitz-Monowitz, for example, was never completed, and never managed to produce any buna, though a facility to manufacture methanol, used in aircraft fuel and explosives, began operating in October 1943; by late 1944, it was producing 15 per cent of Germany’s total output of the chemical. In the longer term, the Monowitz factory did become a major producer of artificial rubber, but only well after the war was over, and then under Soviet occupation.

136

A similar enterprise built using the labour of concentration camp inmates, among others, at Gleiwitz, cost the chemical firm Degussa 21 million Reichsmarks by the end of 1944, while sales from the products it was beginning to turn out netted no more than 7 million, and the facilities constructed by the prisoners were dismantled for their own use by the Soviet forces, after which what was left was nationalized by the Polish government. The eagerness of business to use the concentration camp system as a source of cheap labour, especially in the last two years of the war, reflected longer-term goals than the gaining of instant profits . By 1943, most business leaders realized that the war was going to be lost. They began to look ahead and position their enterprises for the postwar years. The safest way of investing was to acquire real estate and plant, and for this their factories had to expand to gobble up more land and get more armaments orders from the government. This in turn required the recruitment of more workers, and business leaders did not mind too much where they got them from. Once they acquired the workers, businesses often made their own decisions as to how they were to be exploited, regardless of the instructions of central planning bodies. The provision of forced labour, and still more the murderous conditions under which it was used, was the responsibility of the SS and the Nazi state. But a large part of the responsibility for its rapid expansion and exploitation lay with the businesses who demanded it.

137

Altogether in the course of the war, some 8,435,000 foreign workers were drafted into industry; only 7,945,000 of them were still alive in mid-1945. Prisoners of war fared even worse: of the 4,585,000 who found themselves engaged in forced labour during the war, only 3,425,000 were still alive when the war ended.

138

The survivors had to wait nearly half a century until they were able to claim compensation.

Speer never achieved total domination over the economy. Although his influence was enormous, much of it depended on smooth cooperation with other interested parties, involving not only Göring and the Four-Year Plan but also the armed forces and their procurement officers such as Milch and Thomas, Sauckel and his labour mobilization operation, the Reich Ministry of Economics and the SS. In his memoirs, Speer drew a sharp contrast between the years when he was in charge and what he portrayed as the administrative chaos that preceded them; the contrast was overdrawn.

139

On the one hand, Fritz Todt had already achieved a degree of centralization before his death; on the other hand, the administrative ‘polycracy’ that many historians have identified in the arms economy before Speer continued right up to the end of the war.

140

Speer did his best to master it, but he never quite succeeded. Just as importantly, Speer was able to benefit from Nazi conquests. When taken together with the looting and forced requisitioning of vast amounts of foodstuffs, raw materials, arms and equipment, and industrial produce from occupied countries, with the expropriation of Europe’s Jews, with the unequal tax, tariff and exchange relations between the Reich and the nations under its sway, and with the continual purchase by ordinary German soldiers of goods of all kinds at an advantageous rate, the mobilization of foreign labour made an enormous contribution to the German war economy. Probably as much as a quarter of the revenues of the Reich was generated by conquest in one way or another.

141

Yet even this was insufficient to boost the German war economy enough to enable it to compete with the overwhelming economic strength of the USA, the Soviet Union and the British Empire combined. No amount of rationalization, efficiency drives and labour mobilization would have worked in the long run. The German military successes of the first two years of the war depended to a large extent on the element of surprise, on speed and swiftness and the use of unfamiliar tactics against an unprepared enemy. Once this element was lost, so too were the chances of victory. By the end of 1941 the war had become a war of attrition, just like the First World War. Germany was simply being out-produced by its enemies, and in the end there was nothing Speer could do to rescue the situation, however hard he tried. This had been clear to many economic managers even before Speer took over in 1942.