The Third World War - The Untold Story (45 page)

Read The Third World War - The Untold Story Online

Authors: Sir John Hackett

Tags: #Alternative History

Air forces were everywhere involved where fighting took place. Over the oceans and their littoral states the aircraft came mainly from carriers and helicopter ships. The greater proportions were mounted from the US Navy’s big carriers, but the French

Foch

and

Clemenceau

and the British

Ark Royal

and

Illustrious

were also in the thick of the battles in the Mediterranean and Atlantic. The United States Navy had nearly 1,500 top-class aircraft and in addition to that global force the USAF’s Pacific Air Force (PACAF), with its headquarters in Japan and wings based in adjacent friendly countries in South-East Asia, as well as a wing of Strategic Air Command’s B-52 heavy bombers on the Pacific island of Guam, all played their part in the peripheral battles.

Over the Atlantic the continuous action of the US Strike Fleet carriers has rightly been well publicized; what is less well known perhaps is that on the submarine front Allied maritime patrol aircraft, operating independently or in conjunction with ships and submarines, took a very heavy toll of Soviet submarines. These aircraft, packed with electronic and sonic detection equipment and ingenious underwater weapons, exceeded even their high peacetime promise. But being large and ‘soft’ they were vulnerable on the ground, and on the eastern side of the Atlantic several were lost early on in the war to missile attacks on airfields from distant Soviet aircraft and submarines. Thereafter these aircraft were dispersed in ones and twos along the European Atlantic seaboard to fight a rather lonely war. With ample facilities for rest and eating on board, and a disregard for peacetime maintenance requirements, the astonishing fact is that many of these aircraft and crews spent more than three-quarters of the whole war in the air, landing only for fuel and food.

Soviet Naval Air Force action to interrupt the all-important Atlantic air bridge sent a number of large US troop transports plummeting into the sea with air-to-air missiles from modified

Backfires, Bears

and

Badgers.

But despite losses and damage the NATO early warning system held up well and USAF F-15

Eagles

from Iceland and RAF

Tornados

from Scotland were a good match for them. Similarly, when the rather inadequate Soviet

Forger

V/STOL aircraft tried to intervene from their .Kiev-class carriers, RAF

Tornados

and US carrier-borne interceptors kept them at bay until the offending mother ships were sunk. Radar and infra-red reconnaissance from high-flying aircraft and satellites in space meant that surprise at sea rested principally with aircraft and submarines.

The United Kingdom and France came under Soviet air attack from the first few hours of the war. Initially it was confined to missiles from

Backfire, Bear

and

Badger

aircraft directed at port installations, airfields, and radar and communications centres, as well as government and military headquarters. Although in no way decisive, these attacks sometimes hit the soft centres of important targets such as the hotel-like building housing the British air traffic control centre at West Drayton on the outskirts of London.

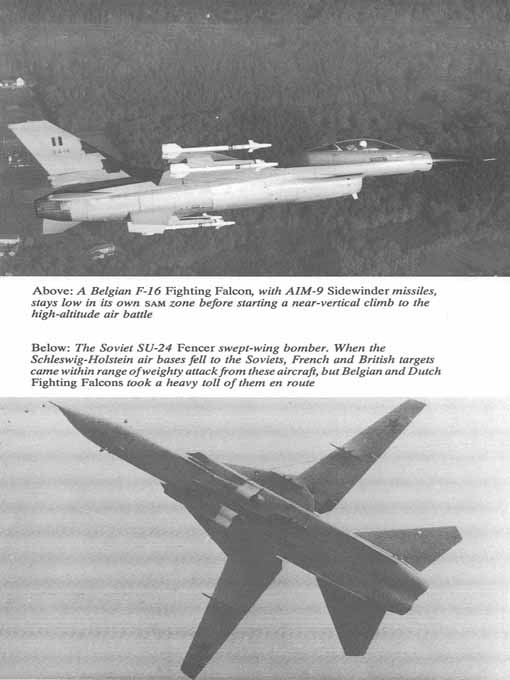

In the first days of the war the Soviet Naval and Long-Range Air Forces could not exert a decisive weight of attack on French and British targets from their distant bases. Their losses were high as they ventured down the Atlantic and the North Sea to get into range with their stand-off missiles. It was not until 8 August, when the Soviet Air Force (SAF) had occupied airfields in Schleswig-Holstein and were able to turn larger numbers of SU-17

Fitter

and SU-24

Fencer

bombers on to French and British targets, that both countries came under really heavy attack. Then US FB-111s, British and German

Tornados,

and French

Jaguars

began pounding the SAF’s new-found airfields and their improvised air defences, while Soviet

Fitters

and

Fencers

suffered heavy losses in the target areas, as well as being mauled on the way by Belgian and Dutch F-16

Fighting Falcons.

The French and British air defence systems were degraded by the gaps torn in the early warning system, the loss of fixed ground radars and airfield damage, but their modern and hardened communications survived well and the airborne early warning (AEW) aircraft proved marvellously adaptable in making good the losses in the ground radar systems. Right up to the end of the war, despite seriously depleted numbers, both French and British air forces were still offering a formidable challenge to SAF aircraft venturing into their air space.

High above the land battle in Germany, the Soviets, with a calculated disregard for losses, swamped the air with their aircraft. The outnumbered, though otherwise generally superior, Allied air forces had to respond with maximum effort. All the pre-war misgivings about what was optimistically called ‘airspace management’ were more than realized. Radars and communications were jammed and close control of fighters from the ground had to be abandoned. The problems of identifying friend and foe and integrating surface-to-air missiles with manned aircraft in the same airspace were so complex and difficult that they could only be met by the simplest of measures. In the absence of a foolproof weapons-locking IFF (identification friend or foe) system both sides inevitably shot down their own as well as the enemy’s aircraft. Broad rules were established within hours by Allied Air Forces Central Europe (AAFCE) giving sanctuary height bands for returning aircraft and ensuring that missile fire from the ground was withheld for a few minutes every hour. Although this sometimes gave SAF aircraft an uncontested run to their targets it was the best that could be done in the intensity of the air battle.

At altitude, the US, Belgian, Dutch and Danish F-16

Fighting Falcons,

together with the US F-15

Eagles,

French

Mirages

and British and German

Phantoms,

hacked away at Soviet

Fishbed, Flogger

and

Foxbat

fighters in a relentless struggle for control of the air. It was reckoned that Allied air forces exacted a toll of 5 to 2 in their favour. This only just matched the advantage in number of aircraft that the Warsaw Pact had over them. Allied losses soon caused great anxiety to COMAAFCE and his air commanders. To add to their difficulties, fresh airfields and ground facilities had to be set up to the west as forward bases in north Germany were overrun or came under direct ground fire as well as air attack. Although it had never been part of NATO’s declared policy to plan for a withdrawal, discreet re-location plans had prudently been made. So when the need arose, NATO air squadrons quickly found themselves operating from unfamiliar airfields in northern France, Belgium and the UK, where there was still some protection from relatively intact air defence systems. USAF and RAF C-130

Hercules,

and French and German

Transall

heavy air transports, as well as helicopters, did magnificent work moving the airmen and their weapons, technical equipment and specialist vehicles back from exposed airfields. Despite chaos on many of the air bases the Allied air forces somehow kept flying and their challenge to the enemy never slackened.

Pilots and navigators in the fast jets had developed split-second reactions and when battle damage sent their aircraft out of control they fired their ejection seats by reflex. Many were lucky enough to parachute into the arms of friendly Germans who helped them back to Allied territory through gaps in the enemy lines. Some air crew returned on foot as many as four times to claim a cockpit seat and rejoin the battle. This proved a significant factor in offsetting the serious attrition of NATO’s air power as each day went by.

Meanwhile, in the important counter-air operations, RAF and GAF

Tornados

and USAF FB-111s were hammering away at Warsaw Pact airfields in East Germany and Czechoslovakia, the

Tornados

flying in the ultra-low mode for which they were designed. These repeated assaults were far from being free of losses, but their specially delivered bombs and mines steadily reduced the enemy’s superior numbers and disrupted the operation of his airfields, thereby redressing the balance in the high- and low-level battles over the front line. These NATO wings and squadrons were also engaged in attacking ‘choke points’ to disrupt and impede Warsaw Pact armoured reinforcements and supplies rolling forward into Western Europe.

After nine days of ferocious air fighting more than half of COMAAFCE’s aircraft and rather less of his air crew had been lost. But the Allied air forces regained the initiative when SACEUR made his historic decision on 13 August to release his dual-capable aircraft to the battle with conventional weapons and to make use of the B-52s standing by at Lajes in the Azores. This was reinforced by COMAAFCE’s parallel decision to commit his remaining reserves, made up of some Italian Air Force squadrons, disembarked French and US naval air squadrons and French and German

AlphaJet

trainers (which, like the British

Hawk,

had a useful secondary war role). These forces had been harboured safely, but with rising frustration among their crews, in southern France and Germany.

All the factors that contributed to the Western allies holding the air against superior numbers will only be known when a full study and analysis of the war is completed, but many of the reasons are clear even now. The importance attached to quality of men and machines was more than justified in battle, but it must be said that had the war continued much longer the decisive factor would have been numbers alone. The commitment of the French Air Force to the air war from the outset was undoubtedly of major strategic importance. The French Tactical Air Force (No. 1 Commandement Aerienne Tactique) with its headquarters at Metz in eastern France provided a flexible framework for the tasking and co-ordination of Allied aircraft drawn back from Germany on to French airfields. Without that prompt commitment and ready adaptability, together with the uncovenanted involvement of several hundred French Air Force

Mirages

and

Jaguars

and their skilled crews, the margin of success in the air might well have rested with the other side.

“When active hostilities began on 4 August 1985, the space orbiter

Enterprise

101, with a four-man crew under Colonel “Slim” Wentworth of the USAF, had already been in orbit on a multiple mission for over forty hours. Photographic and electronic reconnaissance was its initial purpose and, as the orbiter made its regular passes over the Soviet Union ten times a day, an impressive quantity of valuable material had been returned. The spaceship was also, however, furnished with programmes of tapes for broadcasts to the USSR and satellite countries in the event of war, inviting disaffection and revolt. This was perfectly well known, through their own intelligence sources, in the USSR and plans had been made to eliminate

Enterprise

101 if the current state of alert were to be followed by hostilities.

Early on 4 August a

Soyuz

49 mission set out to intercept. Its fourth orbit brought it to within 150 metres of Wentworth’s craft, just as he had himself gone on visual look-out. A laser beam sweep from the Soviet craft blinded him at once. Further sweeps and attack with minelets did such damage to the craft as to put controlled re-entry into the atmosphere and return to earth out of the question. Only a recovery mission by a space shuttle orbiter could effect the rescue of Colonel Wentworth and his companions, and the damage that had been done to

Enterprise

101, particularly to its controls and electric power generators, would result in the failure of life support systems before long. This was, therefore, a matter of urgency.