The Third World War - The Untold Story (46 page)

Read The Third World War - The Untold Story Online

Authors: Sir John Hackett

Tags: #Alternative History

The Colonel’s wife Janet, a tall good-looking brunette, was with Nicholas aged ten and Pamela aged six in the light and generous living room of the Wentworth home in Monterey, California, listening to the dramatic news coming from the commentator on breakfast-time TV. The family usually had breakfast in the kitchen but they were in the living room now because the bigger TV screen was there. They had heard that the country was at war now but what was uppermost in the minds of all three was that a beloved husband and an adored father was already out there in space.

“He’ll get back all right,” said Janet, clearing the breakfast things, “just like the other times.”

She spoke with more confidence than she felt.

The telephone rang.

“Slim’s in trouble,” said a voice that Janet knew well. A close friend of them all was ringing her from Space Control.

“You’ll get it on the news any time now but I thought I’d warn you. He’s hurt, in the eyes, otherwise he’s OK. The ship is in poor shape but we’ll get him back.”

Almost at once there was some news on the TV screen. Even as Janet put down the phone, the commentator was saying: “One of our spacecraft has been damaged in an attack from a Soviet space interceptor. A rescue mission for its crew is being mounted and should soon be under way.”

“Marvellous!” said Janet to the children. “They’ll bring him back all right. You’ll see!”

There was someone at the door. An officer, who identified himself as coming on orders from Space Control, was with two Air Force men bringing in a TV set of a type Janet had not seen before. It was clearly not a model for domestic use. It looked like service equipment. The officer set it up, plugged in the power and made some adjustments.

“You can talk to Colonel Wentworth now,” he said, “when he comes up. He has been told to call you.”

What did all this mean? Janet found herself in the grip of a terrible fear.

She walked around the strange TV set, not touching it, and called the family friend in Space Control.

“There’s a shuttle going up to bring him out, isn’t there?” she asked. “They said there was.”

“I hope that’s true,” was the hesitant reply. “There aren’t many shots left right now. Everything depends on how the Joint Chiefs propose to use them.”

An hour later he called again. She had not yet been able to bring herself to touch the set.

“Janet, bad news. There’s only one rocket left that can get up there before the life support systems run out. The Joint Chiefs have ordered that shot to be used to replace a critical reconnaissance satellite taken out by Soviet interception.”

“You mean - they’re going to let Slim die, out there, when they could save him?”

“They have only one space shot left,” was the reply, “until

Enterprise

103 can be pushed out again. That will take at least three days. With the damage done in the Soviet attack the systems in Slim’s ship won’t last that long. The only shot they have ready to go at Vandenberg is already set to take up the reconnaissance satellite they have to have there and I am afraid there is no way of changing that. The TV set they have brought you will bring in Slim. You can see him and talk to him. Turn it on - but you are going to have to be brave.”

“But. . . but. . . the newsman said a rescue mission was being urgently prepared and would soon be on its way. He said that.”

“I am sorry, Janet, truly sorry. That’s only PR to allay public anxiety. You have to be told the truth.”

Janet was silent for a moment.

“What about the others in the crew out there?” she almost whispered. “What about them and their families too?”

“That’s being taken care of,” was the reply. “But time is running on. You can switch on the set now and pick up Slim.”

She did so. There on the screen was Slim, her beloved Slim, one of the only three people in her whole world who really mattered. He was in the cabin of the spacecraft surrounded by all the gadgetry but blundering about in his spacesuit even more than usual and uncertain in his movements. His eyes looked strange.

“Slim!” she said.

“Hello, love,” he said. “My eyes aren’t so good and I can’t see you but my God it’s good to hear you. How are things?”

“Good,” she lied. “Nicholas and Pamela are here. Say hello to daddy, children.”

“Hello, daddy,” came up in chorus.

“That’s great,” was the reply.

Janet watched a weightless, sightless spaceman fumbling about in the cabin. The voice was the same. That was Slim’s voice.

“Janet,” it said, “I love you.”

“Oh, Slim ...”

“It can’t last long now, perhaps an hour or so, perhaps only minutes. I love you, Janet, I love you dearly and I am switching off.” The image vanished.

Janet, in her much loved and lived in home, sat down upon a sofa, dry-eyed and too stricken even for grief.

Suddenly a wail came from deep within her as from a dying animal.

“I hate you all!” she shouted and then in a flood of tears snatched the children to her and held them close.

When the war ended, a space mission recovered the orbiting bodies of the Captain and crew of

Enterprise

101 and brought them back to earth for burial with military honours in Arlington National Cemetery. The occasion was made an important one. The President sent an aide. Janet Wentworth stayed away.”*

* Mary McGihon, Women in War (Dutton, New York 1986), p. 348.

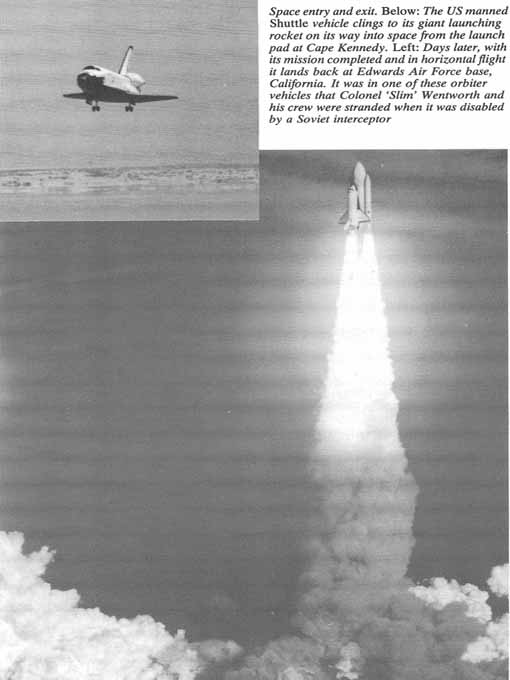

In the three decades before the war, with vast investment and marvellous inventiveness from the superpowers, space technology and its applications raced ahead. Apart from well-publicized programmes for peaceful purposes, there was a strong military thrust behind this effort. All space activity had some military significance but at least 65 per cent of the launches before the war were for military reasons only. By January 1985 the Soviet Union had made 2,119 launches compared with 1,387 by the United States. The latter generally used bigger launching rockets with heavier payloads and their satellites had longer lives and wider capabilities.

Among the military tasks performed by unmanned satellites were reconnaissance, by photographic, electronic, radar and infra-red means; the provision of communications, early-warning, navigational and meteorological stations; and finally there were the interceptor/destroyer (I/D) counter-satellites. Manned vehicles like the orbiter

Enterprise

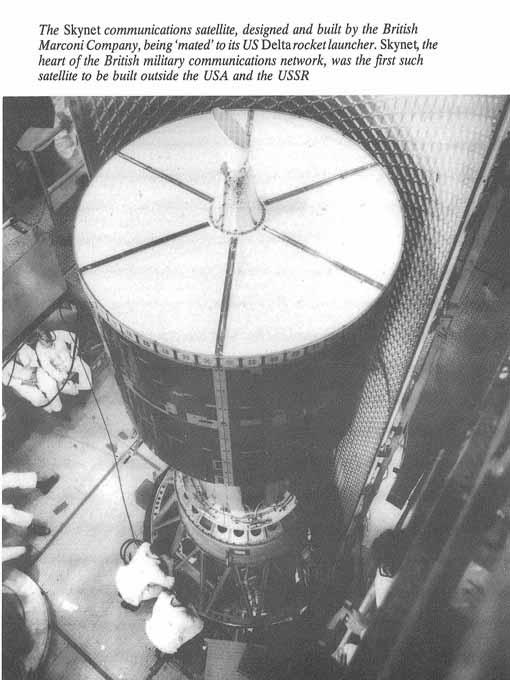

101 were reserved for combinations of tasks which were interdependent or where the opportunity might be fleeting or variable. China, France and Britain also had modest space programmes and put up satellites for research and communications. France and China used their own launchers while the British, who were considerable designers and manufacturers of satellites, depended on US launchers, as of course did NATO, which had a three-satellite communications system.

Before the war ordinary people around the world had little idea of what was going on far above them. This was principally because much of it was shrouded in secrecy, but it was also because their attention was only drawn to space sporadically when people were shot up into it and the TV cameras followed their progress. As things turned out, heroic exploits in space did not figure much in the war. Human beings were needed in space for certain tasks and especially so in the early days of the research programme. When it came to military applications they were usually more of an encumbrance than an advantage. There were notable exceptions when multiple tasks needed direct human judgment and control. Colonel Wentworth’s tragic flight in

Enterprise

101 was a dramatic example. But in the main space was best left to the robots.

To appreciate what happened in space during the war a little understanding of the governing science is helpful. Man-made earth satellites have to conform, as do natural planets, to laws discovered in the seventeenth century by the German philosopher/scientist Johann Kepler. What is probably most significant in the context of this book is that the plane of an earth satellite (or planet) will always pass through the centre of the earth. Under the inexorable discipline of this and the other laws, the movement of satellites is inherently stable and predictable. They can only be manoeuvred by the thrust of ‘on-board’ propulsive forces, usually in the form of liquid or solid fuel rocket motors. These manoeuvring engines and their fuel have of course to be carried up from the earth in competition with all other payloads. As the fuel is quickly exhausted, manoeuvrability is limited. It has in any case to be paid for at the price of other payloads.

The amount of electric power available to activate the satellite’s systems is another limiting factor. Solar cells can convert the sun’s rays into electricity quite readily but there are early limits to the power that can be generated and stored in this way. That is why satellite radars, which played such an important role in the war, were at some disadvantage. Radar hungers greedily for electric power. It was for this reason that the Soviet Union made use of small nuclear reactors as power generators in its radar reconnaissance satellites. It may be recalled that it was a Soviet satellite, undoubtedly engaged in ocean surveillance, that caused worldwide concern in 1978 when it went wrong and scattered radioactivity over northern Canada as it burnt up on falling back into the atmosphere.

Even without such mishaps a satellite’s useful life does not last for ever. It is largely determined by the height of its orbit and the endurance of its power supply. The exhaustion of its power supply sets an obvious limit to its functional life as distinct from the life of the vehicle. The lives of satellites range from days and weeks to (theoretically) thousands of years, depending on their orbits. Generally speaking, the lower the orbit the shorter the life and vice versa. The height of the orbit is determined by the characteristics of the satellite’s launch and is set to suit the tasks it has to perform. Photographic satellites are usually the lowest and are set as low as 120 kilometres from the earth. At the other end of the scale, the United States nuclear explosion detection VELA (velocity and angle of attack) satellites were pushed out as far as 110,000 kilometres into space in the war.

Although space enables man-made objects to move at fast speeds over great distances in near perpetual motion, everything that moves in space is a captive of Kepler’s laws. Once a satellite is in undisturbed orbit it will turn up precisely on time in its next predicted position above the earth. Manoeuvring can change the height or the plane of the orbit but at the end of the manoeuvre the satellite - unless it is brought back into the atmosphere - settles once again into a predictable orbit. So although the exact purposes of some of the earth satellites were not always known in the years before the war, space was very ‘open’ and all the satellites, old booster rockets and other debris orbiting the world, were monitored, numbered and registered in computers at scientific agencies like the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough, England. Indeed, under a widely accepted United Nations convention (with the USSR among its signatories), countries were obliged to notify the launch and leading parameters of every satellite. Within broad limits this was done.

Satellites can be seen by the naked eye at night when they reflect the sun’s light, but more scientifically they are tracked by telescopes, radar, and electronic means. Space activity is so open to observation and deduction that the news that Plesetsk, in the north of the USSR, was the Soviet Union’s major launch complex first came to the knowledge of the world from Kettering Boys’ School in England. A group at the school under the leadership of an enthusiastic science master kept a continuous watch on space and periodically released details of earth satellites that had newly arrived in orbit.

Among many advantages that flowed from pre-war space programmes was the acceptance by the superpowers (because of its scientific inevitability) of the concept of ‘open space’. This removed one of the difficulties in the strategic arms limitation and reduction negotiations (SALT and START), in that numbers of launchers and missile sites could be so easily verified from space reconnaissance. Verification by ‘national technical means’ was the euphemism adopted in protracted negotiations over satellite surveillance. Both sides knew exactly what it meant. Such reconnaissance had its limits: it could not count reserve missiles kept concealed, nor could it penetrate the secrets of the multiple re-entry vehicles within the nosecones of the missiles themselves.