The Transformation of the World (27 page)

Read The Transformation of the World Online

Authors: Jrgen Osterhammel Patrick Camiller

Efforts to grasp the actual power relations in a region were by no means ruled out. Between 1843 and 1847, a commission made up of Iranian, Ottoman, Russian, and British representatives struggled to come up with a border between Iranian and Ottoman jurisdictions that would be acceptable to all sides. The basis of the negotiations was that only states, not nomadic tribes, would be recognized as having sovereignty over a land, and both parties submitted reams of historical documentation in support of their claims. In practice, of course, the Iranian state could not force all the tribes in its borderlands to submit to its authority.

145

New measuring instruments and geodetic procedures made it possible to fix the borders with unprecedented precision. The border commissionsâa second one followed in the 1850sâwere unable to solve the problem entirely, but they made both parties more attentive than before to the value of their lands, thereby speeding up the process of territorialization independently of any “nationalism.” It became quite common to call in mediators, often representing the British hegemonic power, as in the border demarcation dispute between Iran and Afghanistan.

In Asia and Africa, when the colonial powers introduced their fixed linear boundaries (which they automatically took to be the mark of superior civilization), the prevailing conception was still one of porous and malleable intermediate zones that not only defined spheres of sovereignty but also separated linguistic groups and ethnic communities from one another. These different ideas clashed on the ground more often than around the negotiating table. Usually it was the locally stronger side that prevailed. In 1862, when the Russian-Chinese frontier was redrawn, the Russians imposed a topographical solution even though it often separated tribes belonging to a single ethnic group, such as the Kirghiz. Russian experts

arrogantly dismissed Chinese arguments on the grounds that they could not take seriously the representatives of a nation that had not yet mastered the rudiments of cartography.

146

When a European conception of borders conflicted with another approach, the European one would prevail, and not only because of the power asymmetry. The Siamese state, with which the British more than once negotiated to fix the border with colonial Burma, was a respectable partner that could not be simply duped. But since the Siamese thought of a border as an area within effective reach of a guarded watchtower, they failed to understand for a long time why the British insisted on the drawing of a boundary line. So Siam lost more territory than was necessary.

147

On the other hand, in Siam as in many other places, repeated efforts had to be made to find criteria for the definition of borders. The imperial powers rarely appeared with intricate maps in the areas that required demarcation; “border making” was often an improvised and pragmatic activity, albeit one with consequences that were hard to reverse.

In extreme cases, the razor-sharp borders that the nineteenth century inaugurated had entirely destructive effects. This was especially true in areas with a nomadic population, such as the Sahara, where such a frontier might suddenly block access to pastureland, watering holes, or sacred places. Most often, howeverâthere are good examples from sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asiaâdistinctive societies grew up on both sides of the border membrane, in which the location was used in productive ways appropriate to people's life circumstances. This might mean using the border as a defense against persecution: for example, Tunisian tribes sought refuge with the French-Algerian colonial army; people from Dahomey ran away to neighboring British Nigeria to escape from French tax collectors; and persecuted Sioux followed their chief Sitting Bull into Canada. The actual border dynamic, in which local traders, smugglers, and migrant workers also played an important role, often bore only a loose relationship with what the maps showed. New opportunities for making money offered themselves in local border traffic.

148

Borders had yet another meaning in high-level imperial strategies: a frontier “violation” again and again served as a welcome pretext for military intervention.

The nineteenth century saw the birth and spread of the clearly marked territorial limit as a “peripheral organ” (Friedrich Ratzel) of the sovereign state, equipped with symbols of majesty and guarded by policemen, soldiers, and customs officials. It was at once a by-product and marker of the territorialization of power as control over land became more important than control over people. Sovereign authority was no longer invested in a personal ruler but in “the state.” Its territories had to be contiguous and rounded off: scattered holdings, enclaves, city-states (Geneva became a canton of Switzerland in 1813), or political “patchwork quilts” were now seen as anachronisms. In 1780 no one thought it strange that Neuchâtel in Switzerland should be subject to the king of Prussia, but by the eve of its accession to the Swiss Confederation in 1857 this had become a

historical curiosity. Europe and the Americas were the first continents where the territorial principle and the state border gained general acceptance. Things were less clear within both the old and the new empires, where borders were partly administrative divisions without deeper territorial roots, and partly (especially under conditions of “indirect rule”) reaffirmations of precolonial domains. Borders between empires were seldom marked with an unbroken line in the terrain, and it was scarcely possible to guard them as closely as a European national border. Every empire had its open flanks: France in the Algerian Sahara, Britain on the North-West Frontier of India, the Tsarist Empire in the Caucasus. The historic moment for the state frontier therefore came only in the post-1945 age of decolonization, with the formation of a plethora of new sovereign states. The same era saw the division of Europe and Korea by an “iron curtain,” a frontier militarized as never before, whose integrity was guaranteed by nuclear missiles as well as barbed wire. It was thus in the 1960s that the obsession of the nineteenth century with borders came to full fruition.

PART TWO

Â

PANORAMAS

CHAPTER IV

Â

Mobilities

Â

1 Magnitudes and Tendencies

Between 1890 and 1920, a third of the farming population emigrated from Lebanon, mostly to the United States and Egypt. The reasons for this had to do with an internal situation bordering on civil war, the discrepancy between a stagnant economy and high levels of education, the restrictions on freedom of opinion under Sultan Abdülhamid II, and the attractiveness of the destination countries.

1

Even in these extreme circumstances, however, two-thirds stayed at home. The older style of national history had little feel for cross-border mobility; global historians sometimes see

only

mobility, networking, and cosmopolitanism. Yet both groups should be of interest to us: the migrant minorities and the settled majorities visible in all nineteenth-century societies.

This cannot be discussed without numbers. In the nineteenth century, however, population statistics were often highly unreliable. Late eighteenth-century travelers to Tahiti, an earthly paradise that then aroused special “philosophical” interest, varied in their estimates between 15,000 and 240,000; a recalculation on the basis of available clues yields a figure slightly above 70,000.

2

When a national movement arose in Korea in the 1890s, its early activists were outraged that no one had ever taken the trouble to count the number of subjects in the kingdom. Estimates ranged widely between 5 million and 20 million. Only the Japanese colonial authorities established a figure: 15 million in 1913.

3

Meanwhile, in China the quality of statistics deteriorated as the central state grew weaker. The figures most often used today for 1750 and 1850â215 million and 320 million respectivelyâare cited with greater conviction than the usual later total of 437â450 million for 1900.

4

The Weight of the Continents

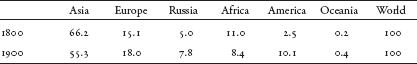

Asia has always been the most populous region of the world, although the size of its lead has varied considerably. Around 1800, some 66 percent of mankind lived in Asia. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the relative demographic weight of Asia had been increasing. This is reflected in the surprise that European travelers expressed about the “teeming human mass” in countries such as China and India. At that time a high population was considered a sign of prosperity; the Asiatic monarchs, we repeatedly hear, could count themselves fortunate that they had so many subjects. Then, in the nineteenth century, Asia's share of the world population fell dramatically, down to 55 percent around 1900.

5

Did Europeans, often unaware of such estimates, suspect this when they had the impression of Asia's “stagnation”? In any event, there was a lack of demographic dynamism. Even today Asia has not regained the share it had in 1800. Who was chipping away at Asia's leading position (see

table 1

)?

Table 1: World Population by Continent (in percentages)

Source:

Calculated from Livi-Bacci,

World Population

, p. 31 (Tab. 1.3).

The estimates show that Asia's loss of quantitative share is correlated with the rise of Europe and, more generally, the Western hemisphere.

6

Africa, which probably had a larger population than Europe between 600 and 1700, was afterward rapidly overtaken as Europe's demographic growth accelerated. The population of Europe (not including Russia) soared between 1700 and 1900 from 95 million to 295 million, while that of Africa crept up from 107 million to 138 million.

7

At least demographically, the “rise of the West”âwhich should include the European immigration to Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazilâwas an incontrovertible fact in the nineteenth century. Population growth rates differed within a world total that was increasing more slowly than it has since the latter part of the twentieth century. Between 1800 and 1850, the number of people living on planet Earth rose by a yearly average of 0.43 percent. In the second half of the century, the rate of increase accelerated to 0.51 percentâwhich is still little in comparison with the 1.94 percent growth rate reached in the 1970s.

8

Major Countries

In the nineteenth century there were still many countries with a very small population. Greece, at the time of its founding in 1832, had fewer than 800,000 inhabitants, half as many as London. In 1900, Switzerland, with its 3.3 million citizens, equaled present-day Berlin. At the beginning of the nineteenth century the Canadian giant had 332,000 inhabitants of European origin; that number passed one million by 1830. Australia had its first big expansion with the mid-century gold fever, reaching the one-million mark in 1858.

9

Which were the populous countries at the other end of the spectrum? The best data we have are for 1913. For a world ruled by empires it is somewhat anachronistic to take today's kind of nation-state as the reference. It is therefore best to be more flexible and to inquire about the major composite polities of the day (see

table 2

).

Table 2: The World's Most Populous Political Units in 1913 (in millions of inhabitants)

British Empire | 441 (of which UK: 10.4 %) |

Chinese Empire | 437â450 (of which Han Chinese: 95 %) |

Russian Empire | 163 (of which ethnic Russians: 67 %) |

United States Empire | 108 (of which the 50 states: 91 %) |

French Empire | 89 (of which France: 46 %) |

German Reich (with colonies) | 79 (of which Germany: 84 %) |

Japanese Empire | 61 (of which Japanese archipelago: 85 %) |

Netherlands Empire | 56 (of which the Netherlands: 11 %) |

Habsburg Monarchy | 52 |

Italy | 39 (of which “the Boot”: 95 %) |

Ottoman Empire | 21 |

Mexico | 15 |

a

Census of 1897, including 44% Great Russians, 18% Little Russians, 5% White Russians.

b

1910.

c

Without Egypt, prior to Balkan wars of 1912â13.

Sources

: Maddison,

Contours

, p. 376 (Tab. A.1); Etemad,

Possessing the World

, p. 167 (Tab. 10.1), 171 (Tab. 10.2), 174 (Tab. 10.3), pp. 223â26 (App. D); Bardet and Dupâquier,

Histoire des populations de l'Europe

, p. 493; Bérenger,

Habsburg Empire

, p. 234; Karpat,

Ottoman Population

, p. 169 (Tab. I.16.B);

Meyers GroÃes Konversations-Lexikon

, vol. 17, 6

th

ed., Leipzig 1907, p. 295.