The Transformation of the World (28 page)

Read The Transformation of the World Online

Authors: Jrgen Osterhammel Patrick Camiller

What stands out in these statistics?

All

major states were constituted as “empires.” Most called themselves such. The only one that did not refer to itself officially in this wayâthe United Statesâshould nevertheless be counted among the empires; the Philippines, over which the United States took sovereign control in 1898, was one of the most populous colonies anywhere in the world. Although it could not compete with the two giant possessions of British India and the Dutch East Indies (today's Indonesia), its population of 8.5 million was only slightly smaller than that of Egypt and larger than those of Australia, Algeria, or German East Africa. The most populous sovereign country that neither possessed overseas colonies nor constituted a spatially contiguous multinational empire was Mexico; its fifteen million inhabitants put it on a par with a sizable colony such as Nigeria or Vietnam. But Mexico too, torn by revolution and civil war in 1913, was no model of a compact and stable nation-state. In Europe, Sweden with six million inhabitants was the most populous nonimperial country.

Demographic size did not translate directly into world power status. In the age of industrial rearmament, absolute population figures were for the first time

in history no guarantee of political weight. China, the strongest military power in Asia around 1750, was by 1913 scarcely capable of foreign policy activity and militarily inferior to the much smaller Japan (with 12 percent of China's population). The British Empire too, which India boosted to number one in the world in terms of population size, was not in reality the all-dominating superpower of the fin de siècle. But it did hold immense human and economic resources, and the First World War would show that it knew how to mobilize them in case of necessity.

Table 2

reflects the overall relationship of forces on the international stage, though not exactly in their ranking order. Britain, Russia, the United States, France, Germany, Japan, and to some extent also the Habsburg Monarchy were the only Great Powers in 1913âthat is, the only countries with the capacity and the will to intervene beyond their own immediate region.

Certain cases are particularly striking. The Netherlands was a very small European country with a very large colony. Indonesia had a population of fifty million, considerably larger than that of the British Isles and only slightly below that of the entire Habsburg Empire. It was demographically eight times the size of the mother country. The Ottoman Empire's humble ranking in the table may seem surprising, but it is the result of continual territorial shrinkage and a low natural rate of demographic reproduction; the loss of the Balkans should not be given undue importance in view of its sparse population. So, if we leave aside Egyptâwhich nominally belonged to the Ottoman Empire throughout the nineteenth century (until the British declared a protectorate in 1914) but was never actually ruled from Istanbulâthen the population total even before its great loss of territory at the Congress of Berlin in 1878 was no more than twenty-nine million.

10

For demographic reasons alone, the early modern Mediterranean and West Asian superpower could barely stay in the race in the age of imperialism.

Paths of Growth

Asia's high absolute population concealed, as we have seen, a

relative

demographic weakness. Nowhere in the nineteenth century did it attain the extraordinarily high growth-rates that have molded our image of the twentieth-century “third world.”

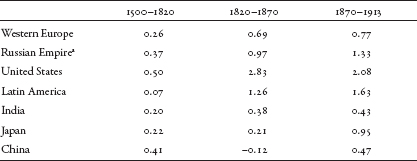

The most astonishing figure in

table 3

has to be China's negative population growth in the “Victorian” age, coming as this did after an early modern period when its rate of increase had been higher than the average in Europe or other parts of Asia. The explanation lies not in anomalous Chinese reproductive behavior but in violence on a huge scale. Between 1850 and 1873, unrest of a destructiveness not seen elsewhere in the nineteenth century raged over large parts of the country: the revolution of the Taiping movement, the guerrilla war of the Nian rebels against the Qing government, and the Muslim revolts in the Northwest and in the southwestern province of Yunnan. In the five eastern and central provinces most affected by the Taiping revolution (Anhui, Zhejiang, Hubei, Jiangxi, Jiangsu), the population declined from 154 million to 102 million between 1819 and 1893; a figure of 145 million was not reached again until the census of 1953. In the three northwestern provinces where the Muslim unrest was concentrated (Gansu, Shanxi, Shaanxi), the population fell from 41 million in 1819 to 27 million in 1893.

11

Grand totals of the numbers killed in the Taiping Revolution and its bloody suppression should be treated with great cautionâpartly because it is hard to distinguish between direct victims of violence and those who died as a result of the mass starvation bound up with revolution and civil war. However, figures as high as 30 million have received the endorsement of leading experts in the field.

12

The most recent estimate, based on research by Chinese historians, even arrives at a total death toll of 66 million.

13

The difference is not really relevant; what counts is the unrivaled scope of this man-made disaster.

Table 3: Population Growth Rate in the Major World Regions (annual average percentages in period)

a

Within frontiers of USSR (without Poland, etc.).

Source

: Simplified from Maddison,

Contours

, p. 377 (Tab. A.2).

The comparatively low Asian growth rates are surprising not only from the vantage point of the early twenty-first century but also against the background of deeply rooted European stereotypes of Asia. The great theorist of population Thomas Robert Malthus, whose analysis of trends in Western Europe and especially England before the nineteenth century has essentially stood the test of time, claimed that Asian peoples, and particularly the Chinese, differed from Europeans in being incapable of “preventive checks” on their fertility that would spare them the extreme poverty resulting from food shortages. At regular intervals, unrestricted population growth had run ahead of a constant level of agricultural production, until “positive checks” in the form of deadly famines had restored equilibrium. The Chinese had not managed to escape this vicious circle by planning their reproductive behavior (e.g., by marrying later). Malthus's account, however, was based on the anthropological premise that “Asiatic man,” being less rational and closer to nature than Europeans, had been unable to achieve the leap in civilization from the realm of necessity to the realm of freedom. For two hundred years after its publication in 1798, his thesis was repeatedly left unexamined.

Even Chinese scholars perpetuated the image of China as a country in the grip of mechanisms of poverty and hunger.

14

Things look different today. The fact that China had unusually low demographic growth in the nineteenth century is not disputed, but the reasons for it are. It is not at all the case that the Chinese reproduced in a blind instinctual manner and were then regularly decimated by ruthless natural forces. New research has shown that China's population was perfectly capable of making reproductive decisions; the chief method was the killing of new-born babies and neglect at later stages of infancy. Evidently Chinese farmers did not regard such practices as “murder”; they assumed that human life began around the sixth month after birth.

15

Infanticide, a low rate of male marriage, low fertility in marriage, and the popularity of adoption added up to a characteristic demographic pattern in the nineteenth century, which was the Chinese response to their straitened circumstances. The low “normal” rate of population growth, which various calamities turned into negative growth in the third quarter of the century, involved conscious adjustment to a falloff in resources. The contrast between a rational, provident Europe and an irrational, instinctual China gone to ruin does not stand up to scrutiny.

Similar points have been made about Japan. A century and a half of population growth under conditions of internal peace came to an end in the first half of the eighteenth century. This slowing was not due mainly to food shortage or natural disasters but rather to a widespread desire on the part of individual families to maintain or improve their living standardsâand thus to preserve their status within the village.

16

As in China, infanticide was a common means of population control, but here it served more optimistic goals than a mere adaptation to scarcity. Shortly before the onset of industrialization in the 1870s, Japan left the demographic plateau of its “long” early modern period and entered a period of constant growth that (with the exception of the years from 1943 to 1945) lasted until the 1990s. In its early stages this was driven by higher birthrates, lower infant mortality, and increased life expectancy. The background factors were an increase in domestic rice production and grain imports, together with advances in hygiene and medical care. The demographic stability of Japan in the late Tokugawa era had not been an expression of Malthusian hardship, but had resulted from the achievement of a frugal yet, in global terms, respectable degree of prosperity. The new upward trend after 1870 was a concomitant of modernization.

17

The most remarkable development in Europe was the biological spurt in British society. In 1750, England (without Scotland!) was demographically the weakest of the leading nations of Europe, with a total population of 5.9 million. The France of Louis XV was more than four times larger (25 million), and even Spain was considerably more populous (8.4 million). Over the next hundred years England rapidly caught up and overtook Spain, and narrowed the gap with France to less than 1:2 (20.8 million for England, Wales, and Scotland in 1850, against 35.8 million for France). By 1900 Britain (37 million) was all but level with France (39 million).

18

Throughout the nineteenth century it had averaged by far the highest rate of population growth (1.23 percent per annum) of all major European countries. Even the lead over the second-placed Netherlands (0.84 percent) was immense.

19

The population of the United States grew constantly, in the most exciting demographic story of the nineteenth century. Whereas the German growth-rate in 1870 was still a touch ahead, the United States by 1890 had left

all

European countries (except Russia) far behind. Between 1861 and 1914, the population of Russia more than doubled, keeping pace with England during the same period. The same trend was apparent in the Tsarist Empire as a whole; colonial expansion into Inner and East Asia did not play a major role in this, since the newly acquired territories were sparsely populated. So, at almost the same time as Japan, Russia entered a phase of rapid population growth, especially in the countryside. The Russian peasantry in the last half-century of the ancien régime was among the fastest-growing social groups in the world. Russia offers a rare example for the period of a country whose rural population grew faster than its city-dwellers.

20

If an attempt is made to organize the quantitative country statistics into a qualitative picture for the century between circa 1820 and 1913, then three categories appear across the continents:

21

(1) Temperate zones where frontiers could to a large extent be opened up underwent

explosive population growth

, even given the fact that the low starting point makes it appear particularly striking in the statistics. The population of the United States increased tenfold, and similarly extreme trends were apparent in the “neo-Europes” (the “Western offshoots” previously often known as “white settler colonies”) of Australia, Canada, and Argentina.

(2) The other extreme of

slow growth bordering on

stagnation

was present not only in northern and central India and China (and Japan before roughly 1870) but also in the middle of Europe. Nowhere was this as marked as in France, which in 1750 had the largest number of inhabitants in Europe yet by 1900 had been almost overtaken even by Italy. This slowdown was not due only to dramatic external influences. At the time of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870â71, France experienced an acute demographic crisis graver than any other European country had to face in the nineteenth century. War, civil war, and epidemics meant that there were half a million more deaths than live birthsâa deficit scarcely exceeded in the years from 1939 to 1945.

22

However, rather than the expression of a permanent crisis tendency, this was an atypical interlude mainly brought on by an earlier decline in fertility that is difficult to explain. Such a decline, nearly always accompanied with higher living standards, appeared in France before 1800 and in Britain and Germany only after 1870. “Depopulation” became an increasingly important issue in public debate in France, especially after the military defeat of 1871.

23

In Spain, Portugal, and Italy too, the pace of population growth was unusually slow, but unlike France, those three countries were not in the vanguard of social modernization. Demographic inertia is therefore not a particularly good indicator of modernity.