Read The Triumph of Seeds Online

Authors: Thor Hanson

Tags: #Nature, #Plants, #General, #Gardening, #Reference, #Natural Resources

The Triumph of Seeds (32 page)

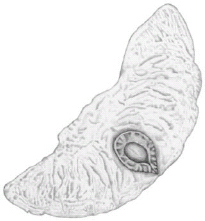

F

IGURE

13.3. Javan cucumber (

Alsomitra macrocarpa

). With its edges stretched into a broad, thin wing, the seed of the Javan cucumber is one of nature’s most efficient airfoils, staying aloft on the slightest breeze and gliding for trips measured not in feet, but in miles. I

LLUSTRATION

© 2014

BY

S

UZANNE

O

LIVE

.

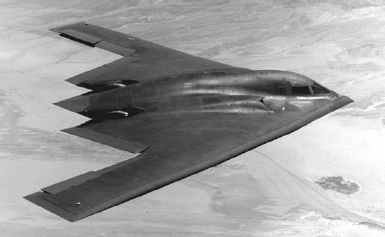

F

IGURE

13.4. The Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit, better known as the Stealth Bomber, took inspiration from the flying-wing design of Javan cucumber seeds. W

IKIMEDIA

C

OMMONS

.

The Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit is better known by its popular name, the Stealth Bomber. Like the seed that inspired it, the B-2’s high-lift, low-drag shape is extremely efficient, making it possible for the plane to fly nearly 7,000 miles (11,265 kilometers) without refueling. As an added bonus, its lack of a tail or other protruding fins helps the B-2 avoid detection by all but the most advanced air defense systems. Though only twenty-one of them have ever been built (at a total program cost exceeding $2 billion per plane), the B-2 is considered a cornerstone of the US arsenal. Designed for both

nuclear and conventional payloads, a single plane has the capacity to extinguish more lives than the entire Civil War. It’s an impressive feat of engineering, but seems ill-matched for the Javan cucumber’s flying wing, a design that evolved not to end life, but to spread it.

Military aviation is a notoriously competitive industry, and any number of defense contractors would love to replace Northrop Grumman’s plane with their own. The Stealth Bomber’s seed-inspired wing gives it an edge, just enough aerodynamic advantage to out-perform its rivals and keep the B-2 program funded. That kind of constant competition helps aircraft design continue to evolve, but it also begs an obvious question about seed dispersal—Which is better, wing or plume? With an eight-foot stepladder, a measuring tape, and an enthusiastic, seed-loving preschooler, it seemed like a question I was well equipped to answer.

O

n a warm summer morning, Noah and I headed down to our back field to play a game we called “seed drop.” The rules were simple. I climbed the ladder and let fly with a series of seeds, while Noah chased them down across the field, planting orange survey flags wherever one drifted to earth. Then we took the measuring tape and saw how far they’d traveled. We started with cotton, but it proved to be something of a disappointment. Even in a moderate breeze, the fluff wafted no more than 16 feet (5 meters) before falling into the grass. That’s better than going straight down, but it would obviously take quite a gale to get cotton seeds across an ocean. Their fibers may be light and prolific, but the seeds themselves remain rather bulky, leading some experts to think flotation may be their most important evolutionary advantage. (It’s telling that, like Darwin’s cotton, the fluffiest varieties all occur near coastlines.) We moved on to dandelions (30 feet [9 meters]), and then tried the plumes from a nearby poplar tree, which drifted all the way to the edge of the forest, 115 feet (35 meters) away.

When it came time to test something winged, I carefully pulled a single Javan cucumber seed from an envelope. (Although my letters

to a botanical garden near Jakarta had gone unanswered, I’d managed to purchase a few from a sympathetic seed collector.) It was easy to see why Igo Etrich had been inspired. As large as my outstretched hand, and thin as a leaf, the seed consisted of a thumb-sized golden disc surrounded by a translucent membrane that crinkled in the breeze like parchment. It looked unbeatable and eager to soar, but the first flight was a total failure.

“That’s no good at all, Papa,” Noah said with obvious disgust, as the seed wobbled and crashed after a few feet, like a paper airplane with a nose-heavy fold. Five more times I climbed to the top rung and let it go, but only once did the seed really start to fly, dipping and swerving like a nervous bird for nearly 50 feet (15 meters). That was farther than cotton, but hardly seemed like a good model for a billion-dollar airplane. I could see Noah’s interest beginning to wane as I climbed the ladder one last time. Again, the seed dipped and fluttered a bit as it descended toward the grass. Then, as if tugged by invisible intent, it caught just the right breeze and wafted suddenly upward. Noah whooped, I raced down the ladder, and the chase was on.

We ran to the edge of the field, following the seed as it soared, turned, and cleared the orchard fence in a series of long swoops and lurches. One of the barn swallows nesting nearby in the eaves of the Raccoon Shack flew over to investigate, circling the seed twice as it continued its ascent. Laughing in sheer wonderment, we watched that seed clear the top of the forest, where it joined a current of faster air and started picking up speed.

“There it goes, Noah!” I heard myself shouting. “We’ll never see it again!”

He still had his orange flag and I was holding the measuring tape, but our contest between wings and plumes was forgotten. We watched that seed fly for the simple joy of seeing something beautiful doing what it is meant to do. Standing there together, heads tilted skyward, we laughed and

laughed until it disappeared from view—a papery wisp at the edge of vision, still rising.

By cosmic rule

,

as day yields night

,

so winter summer

,

war peace, plenty famine

.

All things change

.

—Heraclitus (sixth century

BC

)

E

very family has its lore. My father’s ancestors all hailed from Norway—stoic fisher-folk who plied the fjords in small wooden boats. Nowadays, none of us makes a living with hook and line, but fishing remains an expected activity. It’s hard to find a family photo where someone isn’t holding a dead salmon. My mother called her side “Heinz 57,” a typical American mish-mash that included everything from country doctors and a horse thief to a congressman killed in a duel. When I married Eliza, I joined a clan with a strong farming tradition. I’m still learning her family’s stories, but many of them seem to involve watermelons.

“I grew the first tetraploid watermelon in North America,” Eliza’s grandfather, Robert Weaver, told me with a merry gleam in his eye. At ninety-four, Bob hasn’t lost one whit of his verve for life, and still recalls every detail of the melon years—hand-pollinating countless

blossoms, and trying in vain to sell the results. “I went to see the Burpee boys,” he said, referring to the brothers who ran the famous seed company, “but they didn’t know a chromosome from dirt!”

The word

tetraploid

refers to the number of chromosomes in the nucleus of a cell. As Gregor Mendel learned, plants typically have two sets of chromosomes, one from each parent, a condition geneticists call

diploid

. But sometimes cell division goes wrong, producing seeds with double the normal number. In nature, this is an important source of variation and can lead to new traits, varieties, and species.

Almendro

is a tetraploid, and so is Darwin’s cotton. But in the mid-twentieth century, plant breeders discovered that chromosomes could be

doubled chemically, and that back-crossing a tetraploid with the diploid parent produced infertile hybrids.

*

The upshot for watermelons was a normal-looking, sweet-tasting fruit incapable of filling itself with seeds. For consumers, it offered convenience, and for seed companies it offered control, since farmers and gardeners would have to buy new seeds every year rather than saving their own.

Today, seedless varieties account for over 85 percent of the watermelon market, but Bob sold his shares of the family enterprise decades before it showed a profit. “Millions,” he told me, when I asked how much his brother-in-law had eventually made from the idea. But he said it without a hint of regret. Bob walked away from the melon business to move his family west, settling on an island where, as he put it, “the kids could walk barefoot to school.” They built a house from driftwood logs overlooking a garden with soil so rich he once harvested twenty-four pounds of potatoes from a single plant.

In many ways, Bob’s experience foreshadowed the controversy now raging about the future of seeds. He grew up farming, and later returned to a simple rural lifestyle. But in between he glimpsed the beginnings of genetic modification, a field that now goes far beyond the simple doubling of chromosomes. Modern plant geneticists have the tools to add, delete, alter, transfer, and potentially create specific genes for specific traits. The possibilities are endless, but also troubling. Farmers now face patent disputes over seed saving, open pollination, and other age-old traditions, and critics have raised legitimate worries about the environmental, health, and even moral implications of mixing up genes from different species. Genetically modified seeds have joined a growing list of technologies and innovations that we struggle to make peace with, from drones to cloning to nuclear power. Some people embrace the idea of manipulating seeds, particularly those who stand to profit, but many others are wary or have turned away altogether. There can be no single solution that satisfies everyone, but if you’ve read this far, then you, too, have thought a great deal about seeds, and I hope we can all agree on one point: they are worthy of the debate.

Bob Weaver never farmed commercially again, but gardening remained a central part of his family’s life. He and his wife passed the love of it on to their kids, who passed it on to Eliza’s generation. And it now has a firm grip on Noah. Whenever the Weaver family gathers, conversation eventually turns to who is growing what, and how it’s doing. It’s not unusual for seed packets to emerge, prompting scribbled notes, the folding of ad hoc envelopes, and an immediate exchange of promising varieties. Like the Mende people of Sierra Leone “trying out new rice,” gardeners everywhere share an eagerness to trade seeds, constantly experimenting in whatever plot of earth they till. And through that tradition of gift and receipt, the seeds take on stories.

When I interviewed Diane Ott Whealy at the Seed Savers Exchange, she told me that planting her grandfather’s morning glory was like having him with her. All summer long she saw him there,

in the purple blossoms winking up from a hedgerow, or peering out of the greenhouse. So it is in our garden, where in any given year Eliza might plant the Storage #4 cabbage her grandfather swears by, or her Aunt Chris’s kale (which came to Chris from a one-legged Scots-Irishman named McNaught). Or perhaps she will sow the family’s favorite pole bean, Oregon Giant—hard to come by now unless you save the seed yourself. In exchange, I like to think that one of her relations is growing “Eliza’s lettuce,” a local strain of the Salad Bowl variety that she discovered years ago, gone to seed near her plot in a community garden.