The Tunnel of Hugsy Goode (4 page)

Read The Tunnel of Hugsy Goode Online

Authors: Eleanor Estes

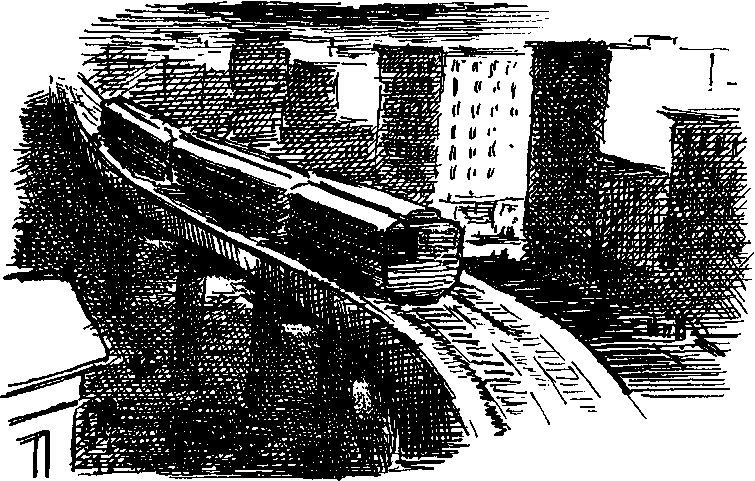

Along came another Myrtle Avenue El. "Come on, Copin. Come on, Copin..." it said to me. The sound of the El is cheerful ... you like to hear it. In the sleet, in fog, in rain or sunshine, you like to hear it and see it.

Well, someday, a day like this one, a Saturday with forced suspending of tunnel work, I'd like to take Tornid over there to Myrtle Avenue ... see the sights. By chance, I had a dollar in my pocket right now. I took it out. I showed it to Tornid. "This dollar," I said to Tornid, "is a marked dollar. The mark on it says, 'Spend me on Myrtle Avenue, Tornid and Copin.' Thank you, I said. 'You're welcome,' it said."

"A talking dollar?" said Tornid.

"Yep," I said. "Money talks ... you've heard of that, even in Grade Three, you've heard of that. Right?"

"Oh, sure," he said.

"So ... come on," I said in an offhand way as though we did this every day. "Time to get going over to Myrtle and spend this talking dollar, partly yours anyway, because you helped me collect and tie up the papers. We'll spend it, eat what we buy, sit on a step and watch the trains go rumbling by."

Tornid was silent. He is not used to doing things that are not allowed. None of the Fabians ever do anything wrong. Without benefit of blasts on the cow horn, my mom's rallying cry, whacks, awful looks, or sarcasm, the Fabians, each and every one of the five, always just naturally do what they are supposed to do. And have perfect manners, say thank you every minute. Bugs me why, sometimes.

Another little train came busily along. We had left the rose of Sharon tree and were standing now at the Alley gate where we could see it, a block away.

"What's that train saying, Tornid?" I asked.

"I dunno," he said.

"It says, 'Come on, Copin. Come on, Tornid.' That's what it is saying."

"Knows my name?" said Tornid. "My fake name?"

"Yes. But ... the trains say something different to everybody," I said.

"Knows many languages?" said Tornid.

"Yep," I said. "And Spanish. Says, right now, says,

'Venite, Tornithos.'

Translated means, 'Come on, Tornid.' And it means ... Now. Hurry!"

What won Tornid in the end was a song I made up on the spur of the moment, the tune and words based on some song I'd heard some time about something else. This was it:

"Oh ... the ... good Myrtle Avenue Line

It gets you there on time.

Shake a leg, shake a leg,

Shake a leg, shake a leg

On the good Myrtle Avenue Line."

As I said, the song won Tornid. We climbed over the Alley gate ... we are used to doing this and didn't tear our clothes on the barbed wire. Then we crawled under the iron gate at the end of Story Street. We were out and on our way to Myrtle Avenue!

Out of sight and out of earshot, we sang at the top of our lungs :

Chapter 5"Oh ... the ... good Myrtle Avenue Line

It makes you feel just fine.

Shake a leg, shake a leg,

Shake a leg, shake a leg

On ... the ... good Myrtle Avenue Line."

The Good Myrtle Avenue Line

"Oh ... it ... gets you there on time ... tum-te-tum, tum-te-tum, tum-te-tum, tum-te-tum ... oh, the good Myrtle Avenue Line..."

Tornid and me felt fine. I bought some chewing gum ... not allowed to have thisâ"Rot your teeth," says my mom ... and a candy bar each in the little store where Star and me, or Steve, buy the Sunday

Times.

I got seventy cents back, two dimes and a Kennedy fifty-cent piece, which was good luckâthere aren't many of them aroundâand bad, because I would not want to spend it. One side of it would say "save me," the other "spend me."

We went down on Myrtle to the corner of George Street where there is a closed-up shoe-shop store, and we sat on its stoop. In the window there were some dusty, high-heeled, pointed-toed ladies' shoes and one enormous pair of a man's black shoes size about eighty. We ate our candy bars. We don't have the knack that Contamination Blue-Eyes does of making a piece of candy last nearly all day, making everybody's mouth water. Yechh!

Across the street was that ancient man sitting in his small square open window on the second floor looking down on Myrtle. Nearby was a spooky-looking store front, covered with dusty brown curtains and a sign that said, "Come in. Mother Fatima will help you." There was a dusty stuffed pigeon in front of the brown curtains and dusty pale blue wax flowers. Looking up the other way, far, far up the tracks, we could see a little train, and soon it would come.

"Next tunnel picture I draw will contain an offshoot from our Alley tunnel to this point here. Then, when me and you have completed our excavations, we can come over here often, even take a ride on the El, return by tunnel, and no one know we been gone," I said.

"Neat," said Tornid.

I counted my money behind Tornid's back, so no wise guy could see me. I had seventy cents left. I put the Kennedy fifty-cent piece back in my pocket and kept the two dimes in the palm of my hand, the price of a token. That's what it costs now anyway ... hope they haven't jumped the price yet. They're talking about doing that, up it to thirty cents. Another good reason for taking our ride now, while it doesn't cost as much. The train was coming nearer, a few people were running up the stairs, not to miss it, the street was vibrating, the train was saying, "Come on, Copin..." I grabbed Tornid's hand ... we joined the other people rushing up the stairs. I bought a token at the booth, shoved Tornid under the turnstile. I dropped my token in the slot, and we were on the platform in time to see the Myrtle Avenue El sway into the station. The whole place shook and vibrated and maybe would fall down before the guys had a chance to tear it down.

The train stopped. "Hurry," I said to Tornid. "We don't want to miss our train," I said, as though we took it every day. The doors opened, we stepped in, the conductor looked up the platform and down the platform, signaled, the doors closed. We raced to the front car and stood at the front door with a view down the tracks. The ancient man, below us now, was still at his window, and he didn't look up at the train as we went by, just waited for his enemies.

My first ride on the Myrtle Avenue El! At last! Wait till I tell Jane Ives! The train started up smoothly. There was only one other person in our car. She sat at the back reading a newspaper instead of looking at the sights. I thought she couldn't hear me, so I sang my song, "Oh, the good Myrtle Avenue Line..."

"Sing," I said to Tornid.

He said, "I don't sing on els."

Then I sang, "It's a long day's night..." Can't see why my mom doesn't like the Beatles ... only likes Bach. De-dum-de-dum-m-m ... dum-m-m dum.... Was I happy!

Tornid looked up at me and smiled. His eyes were shining.

"This is something like, eh, Torny, old boy, old boy?" I moved over a little not to hog the entire best spot in the middle of the front door.

"I can see all right," he said.

But I pulled him over a little anyway so he could see better.

And that's the way we went, the entire way down to the end of the line ... the Jay Street station to be exact. The engineer came out of his cab here, walked through the cars to the back of the train with all his equipment, and got into that cab there. The back was going to be the front now. So we followed right after him. The conductor gave us a thoughtful stare, but he did not look unfriendly. We hoped he would not make us get off and have to pay another fare. All he said was, "Where you two fellas going?" I said, "Back to the George Street station where we got on." And (this shows how many nice guys there are left in the world) he said, "OK."

He picked up some newspapers people who litter had littered, folded them neatly, picked the best one, sat down, and read it. At last we switched over to the other track and started back. We were the only ones making the round trip. It was real neat when another train, coming the other way, came swinging and swaying along. When we passed, each engineer gave the other a toot and a slow wave of the hand.

When we got to the George Street station, Tornid said, "Come on, Copin. We have to get off."

"Cluck!" I said. "Now we have to go to the end of the line the other way, see what it's like up there..."

"I wisht I'd asked my mom or my dad," said Tornid, and looked longingly back at the station left behind.

"Too late now," I said.

The conductor came in, and he sat down in a corner of our car, getting up only at stations. He seemed to have forgotten about us and George Street. He opened up his paper and started to do a crossword puzzle someone else had begun on. I could see this because he was reflected in the window in front of us. If he asked me for a word, it might be "adze" because that is in most crossword puzzles.

It was much farther to the end of the line in this direction than the other. But it was a good ride. Pigeons were being exercised on the rooftops. On one windowsill a white cock crowed when we went by. Now, that was unusual. To the left, far away, we could see the Empire State Building and once in a while glimpsed the East River, so we knew we were still in New York City, though we weren't sure we were in the part of it named Brooklyn.

I wondered if we had been missed and whether someone else had cleaned up the Fabians' yard or if it were being saved for us. Well ... guess where we finally ended up, where the end of the line was? In the middle of a cemetery that stretched as far as eye could see on both sides of the station. It was not a pretty cemetery. If you ever have a chance to ride the Myrtle Avenue El, go the other way, not this.

Finally, back down the tracks, homeward bound we went. I began to sing again and also danced a few steps of the frug. Tornid pulled at my arm. He was embarrassed. "There's a person on the train now," he said. Sure enough. There was ... another lady. I could tellâthe way she was looking at meâshe didn't like the look of me or my hair. So, I looked back at her over my nonshatterable eyeglasses with gold rims. I didn't like the look of her hair either, on the order of an upside-down Baltimore oriole nest. We turned our backs on the lady with the nest hair. I said, "Contamination," and we forgot about her and did not care about her. Anyway, Jane Ives likes my hair, says it is not too long, and in school the kids say I look like Oliver.

Now, on our left, once in a while between buildings, we could see the Williamsburgh Bank building. This has the largest four-faced clock on the top of it that there is in the whole world, according to John, Jane Ives's husband, and he's been almost everywhere. The clock said two-thirty. I couldn't believe my eyes.

"Tornid," I said. "What time is it by that clock up there?"

"Half-past two," said Tornid. "Wow!"

"Must have stopped," I said. "Must not be going."

"Yeah," said Tornid. "Because if it was half-past two, lunch would be over and we haven't had lunch."

Next view of the clock said two thirty-five. It had not stopped, and by now plans were probably being made for our punishments. I tried not to think about these ... they'd be more than cleaning up the Fabians' yard, you can be sure ... as we clickety-clacked our way down â¢the tracks on the home stretch. Pigeons back in now, smells of bread being baked in the famous Italian bakery below where my mom buys pizzas, of Rockwell's chocolates, of coffee. This is the best ride I've ever been on in my entire life. I've never been to Disneyland and can't compare it with those rides. I bet they can't beat this ride there, though, and nobody should ever tear down this famous El ... ever.

The next station was ours. We went to the door. I turned around and looked sternly at Nest-Hair and piercingly through my gold rim eyeglasses, pursed my lips together thoughtfully, and me and Tornid got off. Ready for come what, come may. "The wheels of fate grind slow, but they grind sure," I said. A saying of Mr. John Ives, a man of many sayings.

"That the name of this train ... Fate?" asked Tornid.

"May be," I said.

Down on the street now. Nearly three o'clock. They would not expect us for lunch any more. They would have eaten up all the lunch.

"My legs wobble," said Tornid.

"Mine, too," I said. I bought each of us a hot dog from the man on the street, fifteen cents each without sauerkraut on them, and two orange drinks, ten cents each, and so the "spend me" side of the Kennedy half-dollar had won. Good-by to it, good-by to the El, hello punishments.

We sat down on the same stoop as before, and the antique shoes were still there. It seemed a year since we'd sat here before. I ate my hot dog in about three bites, before Tornid had even taken one. He did not seem hungry. I was putting off the come what, come may ordeal.

Suddenly Tornid yelled. "Hey! There they are, there's my daddy! There's the Pugeot!"

He was right. There they all were, car overflowing with brothers and sisters, his and mine. They were going slowly down the street, opposite us, arms stretching out on both sides of the car, calling, "Timmy, Timmy ... Nick, Nick," to right and to left. They didn't see us because a bunch of men had come out of the bar next door and were standing right in front of us, arguing.

Tornid got up, ready to shout, race across the street, traffic light say go or not. I pulled him back down and clapped my hand over his mouth. "They'll hit you, you crazy?"