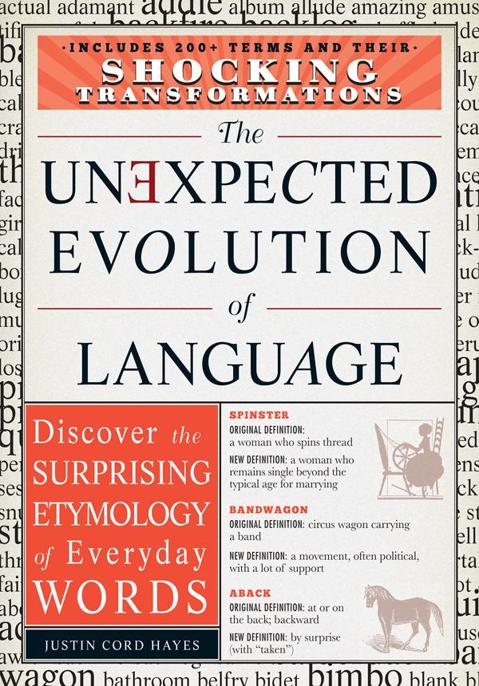

The Unexpected Evolution of Language

Read The Unexpected Evolution of Language Online

Authors: Justin Cord Hayes

Contents

Introduction

English is the mutt, the Heinz 57, the bastard child of every language that came before it. That’s why it’s so inscrutable to those who encounter it after learning their well-behaved, logical languages. Our words trace gnarly roots that sometimes dead end, and we’re certainly not averse to coining words that have no roots or reason at all. (“Hornswoggle,” anyone?)

It’s those gnarly roots that you’ll find in this book. Some of the English words you

think

you’re familiar with actually used to mean something quite different. How on earth does a definition just change, you ask? Well, it depends. The definitions of the words in this book were twisted due to historical events, cultural adjustments, or technological advancements. The fascinating stories behind these transformations are surprising (see entry for “stadium”), thoughtful (see entry for “acquit”), and sometimes pretty funny (see entry for “occupy”). One thing to keep in mind is that “English” is really three Englishes: old, middle, and modern. Ask most people which one was Shakespeare’s purview, and they’ll say, “Oh, he wrote in Middle English.” Nope, sorry. He wrote in Modern English. Don’t let all those “forsooths,” “cozes,” and “fiddlesticks” throw you off.

Before we get started, it’s helpful to know a little bit about the origins of the English language. Old English lasted from roughly

A.D.

700 to about

A.D.

1100. The grammar of Old English was closely related to Latin. Old English, also called Anglo-Saxon, was spoken by the … Anglo-Saxons. These were Germanic tribes who invaded and then settled in portions of what is today Great Britain.

Old English is indecipherable to us today; it’s basically a “foreign” language. Nonetheless, we do have surviving Old English texts such as

Caedmon’s Hymn

. This nine-line poem written in honor of God is the acorn (see entry for “acorn”) from which has grown the mighty oak of literature in English. Written around

A.D.

700, it’s the oldest piece of English literature known to exist. Old English also is the language of the epic

Beowulf

… .

For all intents and purposes, Old English ended with the famous Norman Conquest. The Normans were French and defeated the English, the erstwhile Anglo-Saxons, at the Battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066. Middle English survived until the 1400s. It’s the language of Geoffrey Chaucer, author of the immortal

The

Canterbury Tales.

Though it’s written in Middle English, most people today can read and understand those stories, as long as the text contains plenty of footnotes.

Middle English shifted to Modern English when many in England adopted the Chancery Standard, a form of English spoken in London. The standard was adapted, in part, because of the printing press, introduced to England around 1470. Thus, Modern English took over by the 1500s and holds sway today. It’s the language of everything from Shakespeare to Dickens to Hawthorne to Dickinson to Faulkner to all those annoying bloggers who can’t spell.

Modern English rose at the time of great world exploration and is now the polyglot stew we know and usually love (but sometimes abhor). Perhaps due to its “mutt-like” origins, we English speakers continue to coin words and phrases with a frequency that would have shocked Chaucer … and probably even Shakespeare.

With centuries of history under its belt, maybe it’s not so surprising that English words have changed meanings over the years. Sometimes, we easily can trace why a word once meant “this” but now means “that”; yet, at other times, the only things to rely on are common sense and speculation based on historical trends.

What follows are about 200 words that used to mean one thing and now mean something else. Some of them have changed in logical, sensible ways, while others have undergone the linguistic equivalent of complete reconstructive surgery—shifting, for example, from a verb to a noun or vice versa—bringing them to the point where even these words’ mothers wouldn’t recognize them. But what do you expect from a language that’s the semantic cross between a Dutch elm, an oak, and a Japanese maple?

A

aback

ORIGINAL DEFINITION:

at or on the back; backward

NEW DEFINITION:

by surprise (with “taken”)

You’re most familiar with this word from the expression “taken aback.” Come to think of it … do you

ever

hear the word without “taken” as its partner? When the word first popped up, in the middle of the Middle Ages, you might have.

For example, you might have carried your wares “aback,” meaning “on your back.” Or the wind might have been “aback,” meaning “at your back.” These seem like perfectly reasonable uses of the word “aback,” but they lost favor completely by the middle of the nineteenth century.

The word as we know it today—as part of the expression “taken aback”—came about for nautical reasons. When finicky winds change direction quickly, boats’ sails can “deflate” and hang limply back onto the ship’s mast. Eventually, sailors began to refer to this condition as being “taken aback.”

One hundred years later, the expression became metaphorical. After all, you can imagine that wind suddenly changing direction for no apparent reason was surprising and dismaying. By extension, anytime you are “taken aback,” you are surprised and dismayed.

abode

ORIGINAL DEFINITION:

delay; act of waiting

NEW DEFINITION:

formal word for one’s home

The words “abode” and “abide” spring from the same source. In fact, from the 1200s to the 1500s, they meant the same thing—“wait,” “withstand,” or “tolerate.” The words were connected because of the manner in which Old English verbs were conjugated: “Abode” was a past tense version of “abide.”

Then, during the 1500s and 1600s, “abide” still meant “wait,” “withstand,” or “tolerate,” while “abode” changed to refer to one’s home. One reason for the change is metaphorical. If you think about it, people spend a lot of time waiting at home. In the sixteenth century, people waited for dinner to be slaughtered, for wool to be spun into coats, and for the kids to come home from whatever bad stuff they were doing. Today, people wait for their favorite TV show to come on, and for the kids to come home from whatever bad stuff they’re doing. As people “aboded” in their homes, they just began to refer to their dwellings as abodes.

The modern, mostly European, concept of “right of abode” captures both the old and new meanings of the word. The “right” allows people to be free from immigration authorities and to have a right to work and live in a particular country. Thus, they can “wait” as long as they like in a nation, and have an “abode” there as well.

accentuate

ORIGINAL DEFINITION:

to pronounce with an accent

NEW DEFINITION:

to emphasize

Our world’s increasingly polyglot nature led to the change in the word “accentuate.” Originally, it meant “to pronounce with an accent.” As cultures and their respective languages mingled, people had to work extra hard to be understood. As a result, they spoke carefully so that people could understand their “accentuated” (spoken with an accent) words. Thus, it’s not much of a leap for the word to shift from “speaking with an accent” to carefully “emphasizing” each word so that other people can understand what you’re saying.

After the shift occurred, “accentuate” began to mean “emphasize.” By the middle of the nineteenth century, “accentuate” had all but lost its original meaning. In writing, “accentuate” means to mark with written accents. For example, if you’re writing out the meter of a poem, you use accentuating marks to indicate how to “scan lines” (analyze them rhythmically).

accolade

ORIGINAL DEFINITION:

ceremony conferring knighthood

NEW DEFINITION:

praise; expression of approval

From a Latin word meaning “to embrace around the neck,” an accolade used to include this actual action. An accolade was a formal ceremony that conferred knighthood on a worthy wight (person).

The ceremony went something like this. Royalty would embrace the knight-to-be about the neck, kiss him, and tap his shoulders with a sword. Even today, children still mimic the shoulder-tapping portion of the ceremony.

Thus, from the beginning, an “accolade” suggested praise for accomplishment. But for several hundred years, it referred to the specific ceremony, which contained detailed actions—including the ceremonial embrace that formed the word in the first place.

As knighthood became more of a spectacle (Sir Mick Jagger, anyone?), and knights of old became fodder for the novels of Sir Walter Scott, the word “accolade” lost its connection to a specific ceremony and became instead a generic word for “praise.”

Of course, if you’ve done something really good for your significant other (unexpected flowers, breakfast in bed, etc.), then your accolade may still include an embrace around the neck.

accost

ORIGINAL DEFINITION:

to come up to the side of (focusing on the action of ships)

NEW DEFINITION:

to challenge aggressively

When you hear the word “accost,” you might picture pushy salespeople, debt collectors, pissed-off landlords, or an angry spouse taking you to task for leaving the toilet seat up (again!!). Chances are, you don’t picture boats, but at one time, you would have.

The word “accost” contains the same root as the word “coast” because, initially, the word referred to actions that ships took during battles—or potential skirmishes—at sea. For example, a ship would come up alongside another boat to see if the other ship contained friends or foes. Or, a ship would approach the coastline and threaten a town.

The word also had the milder, non-nautical definition of addressing someone formally, but you will probably encounter this version of “accost” solely in English novels of manners. In addition, Shakespeare occasionally used the word “accost” to mean simply “approach” … minus the aggression.

As piracy and naval battles became less common—though both still occur today, of course—the word “accost” became more generic. It still suggests someone approaching you aggressively, but he or she doesn’t have to be in a boat in order to put you on the defensive.

Trix Are for Women