The Wasted Vigil (25 page)

Authors: Nadeem Aslam

Now he and Casa get to work—silently on the whole, except for a grunt now and then, and with the million-year-old gaze of the demoiselles watching them from far away.

David had collected large stones from along the lake’s shore, some of them covered in brilliant patches of moss, and these are weighing down the plywood leaf.

The main piece of bark is only slightly wider than the widest point of the plywood leaf, so they’ll have to use extra pieces at the sides, sewing them on with the lengths of spruce roots soaked in hot water for flexibility, using the antler-handled awls to make holes for the rows of double stitches.

The excess bark has been bent upwards around the plywood template and stakes have been driven along the outline to keep it folded up.

They are doing this in the shade because the sun would dry out the bark, and they are pouring hot water from a bucket—set on a fire near by—to ensure the bark remains workable.

David tells Casa that this type of boat had been in use for at least fourteen thousand years, that torches would be fastened to the canoes when they were taken out by the Native Americans for night fishing on the lakes of North America.

· · ·

It is an awakening when the generator is installed.

Casa and David work on the bark boat until the sun sets, the gradual disappearance of light in a vast show of overlapping reds above them, sweeping in evenly spaced bands. Then they lift the generator out of the back of the car. And, working together by candlelight for half an hour, they set it going.

Casa tries not to get swept up in everyone’s obvious delight. Like transparent eggs, David has brought boxes of bulbs which Casa fits into the socket in each room, putting chairs or stools on tables to gain the heights, someone always holding the column of furniture for his safety. He takes out the dead bulbs and examines them closely. If the filament is broken—as opposed to burnt away completely—he can manoeuvre the two ends into meeting again, snagging the coils together so that the current can flow through once more.

Suddenly the house is lit up with radiant electricity. It’s as though they had trapped daylight a few hours earlier and have now brought it into the house, hanging a cage from a hook in every room.

It is his first time in the deeper interiors of the house. When the switch is thrown, light shoots out of the bulb and slams into the walls but then it is as though the walls are glowing from within. They also seem to take a step towards him. Colour. He stands inhaling it. Marcus points out various details to him, his talk confusing him, making him feel at times that he doesn’t know much about Islam let alone other religions, that he knows little about Afghanistan let alone the world.

Arriving at the room at the top, however, as he stands in the middle looking around, all he can think of is annihilation.

Fragments of plaster are arranged in the centre of the floor, depicting two lovers with their arms around each other, Marcus carefully removing four pieces for the four legs of the table, so Casa can rise towards the fixture in the ceiling, towering above the image. He stands in a daze: the indecent images on the walls seeming to swell and recede with each thump of his heart.

He had told Nabi Khan that for tomorrow night’s necessity they must be given an adult female.

The lilies stretching their jaws, the smaller blossoms hanging in triangular grape-like clusters from high vines—he does like these painted details, he must admit. But the rest. If all this is what is meant by the word “culture,” then culture is not permitted in Islam. So it is that the Devil has the temerity to say to Allah, “I have added colour to Adam’s story,” and—the senses undermining faith at every turn—no wonder the Saudi fighters want all the mosques here in Asia painted white inside and out, like the ones in their desert homeland.

Music issues from a tape recorder in a stone alcove while he sits in the kitchen with Lara and Marcus, helping them peel boiled potatoes. He gets up and half-fills a glass of water and brings it to the table—for them to dip their fingertips into from time to time because the potatoes are scalding hot. His own Kalashnikov was the authentic article, but there were Pakistani-made copies that heated up when they were fired, obliging a warrior to dip his hand into a puddle during battles.

He wonders what kind of instrument produces the sounds they are listening to.

He doesn’t flinch when David comes in with a bottle of wine and uncorks it and puts it on the windowsill, next to the bowl of water in which there is a fountain pen that Marcus had been cleaning earlier in the day, taking it apart like a rifle.

Before opening the dark-green bottle David asks Casa if he’d mind their drinking it and he shakes his head and smiles. The smell of alcohol reaches him within a minute. That such things are for sale in the cities of a Muslim country.

They weren’t until the West routed the Taliban.

Marcus says that in the year 988 when Prince Vladimir was casting around for a religion for the people of Rus he rejected Islam because he knew about its prohibition on alcohol. As though Casa wants to hear it. Perhaps if Russia had been a Muslim country it would not have given birth to the misfortune of Communism. As a child he had wanted to fight in Chechnya because he knew Communism and equality were a direct rebellion against Islam. The Koran clearly states in sura 16 that:

To some Muslims Allah has given more than He has to other Muslims. Those who are so favoured will not allow their slaves an equal share in what they have. Would they deny Allah’s goodness?

Marcus, who had claimed he was a Muslim, sits drinking wine at dinner. There is indeed no limit to the cunning of the infidels. He deceived the trusting and amenable Muslims of this land just to marry a woman, but at heart he is still a non-believer. No wonder Allah punished him by deranging her, by taking away his hand.

The food bitter in the mouth, he finishes the meal in silence and quickly, and then, clearing away his plate, leaves for the perfume factory, declining their invitation to stay. Walking through the orchard he passes the large aloe vera plant whose thick serrated fingers Marcus slices up with a blade every day, extracting the pulp for Lara’s neck. His head is spining from the scent of alcohol. He drops to his knees close to the saw-edged plant, putting the lantern on the ground and waiting for the wave of nausea to pass. His left hand is in a mane of wild grass and some irregularity in the blades makes him look at them. He lifts the lamp with the other hand and is suddenly clear-headed. The half-green grass conceals a massive landmine. It is only two or so yards from the aloe plant. He withdraws the left hand slowly and stands up. He must calculate, see how this object can be used to his best advantage. He pinches the corner of his mouth between incisors as he stands thinking. A vision in his mind of the Englishman bleeding to death here. One whole sura of the Koran is dedicated to the hypocrites.

They use their faith as a disguise . . . Evil is what they do . . .

He imagines laying out the Englishman before the stone idol’s head and filling up the entire perfume factory with earth, interring them both.

After Marcus is eliminated he could take possession of the house? But what about the other two?

He continues towards the factory, the sky the darkest of blues above him, almost black, the colour he imagines each of their three souls would be if it were stretched thin and nailed to the corners of the sky. Containing just a few scattered points of light.

He goes down into the factory but, unable to jettison the thought of alcohol from his mind, the smell of it still inhabiting his nose, rushes back up and vomits as neatly as a cat in the darkness, shivering, squatting beside the tall tough stems of a weed. The various components of his soul rebel at the memory of having been so close to the forbidden repulsive liquid.

The cold air hits him now. It’s as though he has taken off a metal hat.

He knows he must prevent Marcus and the others from ever venturing near the mine. He cannot bring himself to care about what happens to them, but it’s important that the mine remain intact, to be at his disposal if ever those Americans threaten him again. He’ll lure them to it. It’s his only weapon.

“I read somewhere,” says Lara, “that when Muslims conquered Persia they burnt the libraries as instructed by Omar, the second caliph.”

“That story is probably invented,” Marcus says. “But it was invented by

Muslims

to justify later book burnings.”

“When the thousands of manuscripts were set alight, the gold used in the illuminations had melted and flowed out. It’s odd that they invented this detail too.”

“To make the myth appear convincing, yes.”

Holding a bamboo shaft at either end, they are on their way to the second storey, have been moving through the house to bring down books.

“When in the seventh century,” says Marcus, “the Arabs conquered Persia, Khorasmia, Syria and Egypt, these were rich and sophisticated societies. The ignorant desert Arabs exchanged gold for silver when they entered Persia and made themselves ill by seasoning their food with camphor. One can only wonder, Qatrina would say, at what these lands could have been had they not been set back by the arrival of Islam. In Khorasmia the Arabs killed everyone who could read their own language. Only Arabic was allowed.”

He has stopped on the landing and is touching the tip of the bamboo to a thick volume on the ceiling, brown leather stamped with gold filigree.

“But time moved on and the two peoples changed each other. Eventually it would be the Muslims who’d keep the philosophy of Aristotle alive for the Europeans through the Dark Ages.”

She thinks he is slightly drunk. Lets him talk, following him wherever he goes. Perhaps it’s ebullience brought on by all this light. Or it could just be the company. They are stirring in each other memories of other times.

David has gone outside, saying he remembers burying wine under the silk-cotton tree one year. She enters an unlit room to look for him through the window. Over half the world’s mine dogs are here in Afghanistan.

In this room there is a wall of moonlight at this hour. Something like a flock of hummingbirds sweeps across it. Mites hide in the nostrils of hummingbirds, the Englishman has told her, and when perfume begins to drift over their bodies they know the bird has arrived at a blossom—they climb down and begin to consume the pollen and nectar.

“He’ll be back soon,” Marcus says from the door.

She nods and joins him.

“Were you always interested in perfume?”

“The factory? I started it to give the women of Usha a chance to earn money. Qatrina wanted them to know they could have an independent wage. And this valley has always been known for its flowers. Later when I went to a perfume factory during a visit to Paris, with its large laboratories full of test tubes and pipettes, I told them that my own creations were just a matter of experimenting, of putting things together to see what happened. They laughed. ‘But that’s how we

all

do it, it’s all random—don’t be fooled by the fancy equipment.’ ”

They are sitting next to each other on the stairs.

“I think I hear David. I should go to bed.”

“Stay with us, Marcus.”

“No, you go and find him.”

She watches him leave, clutching the new books. The clerics had the brilliant al-Kindi whipped in public for his words in the ninth century, he said earlier. The Father of the Perfume Industry—as well as philosopher, physician, astronomer, chemist, mathematician, musician and physicist—al-Kindi was sixty years old and the crowd roared approval at every lash. Al-Razi was sentenced to be hit on the head with his own book until either the book or his head split. He lost his eyesight.

It is always the case that where there is power, there is resistance, and so a parent came to the house during the time of the Taliban and asked if Marcus would help his eleven-year-old son with his studies, afraid the boy would forget what he learned in the days before the Taliban. Then more and more parents arrived with the same request, wanting to equip their sons and daughters for the possibilities of the world, rebelling against the Taliban’s insistence that the wings be torn off the children. That was how it began, Marcus, his hand amputated, deciding to secretly tutor Usha’s boys and girls in the perfume factory. Soon it was no longer a case of tutoring. It was a school.

The children were asked to walk to the house in twos and threes to avoid drawing attention to themselves from the Taliban’s Religious Police. One group came in the morning, the other in the afternoon. This way the forty children were divided into two groups of twenty, each group sitting around the Buddha for four hours every day. Marcus tried not to talk of danger with the children: they were there to learn, not discuss problems that could not be solved. The youngest ones had little idea of certain forms of play. If a kite flies too high, one of them asked, does it catch fire from the sun? High on a wall in the kitchen, Marcus painted a diamond, with three coloured bows threaded along its tail, and attached an actual string to it: if a child excelled at his lessons he or she could go and hold the string and pretend to fly the kite as a reward.

An entertainment they had devised on their own had to be stopped when he discovered it to his horror. They banged their feet on the ground where the piano and the two rababs were buried, leaping from place to place, managing to strike some of the keys this way, to vibrate some of the rababs’ strings, and listening as the notes seeped out of the soil.

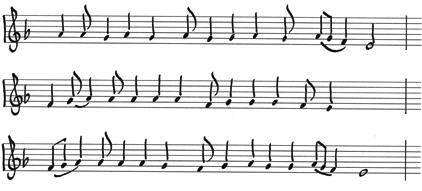

For himself, denied music, he carried strips of paper in various pockets on which he had scrawled musical phrases, his fingertip touching the inked score like a stylus making contact with the groove of a record—