The Weight of the Evidence

The Weight of the Evidence

First published in 1943

© Michael Innes Literary Management Ltd.; House of Stratus 1943-2010

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The right of Michael Innes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

This edition published in 2010 by House of Stratus, an imprint of

Stratus Books Ltd., Lisandra House, Fore Street, Looe,

Cornwall, PL13 1AD, UK.

Typeset by House of Stratus.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library and the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 0755121171 EAN: 9780755121175

This is a fictional work and all characters are drawn from the author’s imagination.

Any resemblance or similarities to persons either living or dead are entirely coincidental.

Note for Readers

Reader preferences vary, as do eReaders.

This eBook is designed to be read by any eReading device or software that is capable of reading ePub files. Readers may decide to adjust the text within the capability of their eReader. However, style, paragraph indentation, line spacing etc. is optimised to produce a near equivalent reflowable version of the printed edition of the title when read with Adobe® Digital Editions. Other eReaders may vary from this standard and be subject to the nuances of design and implementation. Further, not all simulators on computers and tablets behave exactly as their equivalent eReader. Wherever possible it is recommended the following eReader settings, or their equivalent (if available), be used:

Clear Local Data – off; Local Styling – off; Text Alignment – Publisher Default.

Michael Innes is the pseudonym of John Innes Mackintosh Stewart, who was born in Edinburgh in 1906. His father was Director of Education and as was fitting the young Stewart attended Edinburgh Academy before going up to Oriel, Oxford where he obtained a first class degree in English.

After a short interlude travelling with AJP Taylor in Austria, he embarked on an edition of

Florio’s

translation of

Montaigne’s Essays

and also took up a post teaching English at Leeds University.

By 1935 he was married, Professor of English at the University of Adelaide in Australia, and had completed his first detective novel,

Death at the President’s Lodging

. This was an immediate success and part of a long running series centred on his character Inspector Appleby. A second novel, Hamlet Revenge, soon followed and overall he managed over fifty under the Innes banner during his career.

After returning to the UK in 1946 he took up a post with Queen’s University, Belfast before finally settling as Tutor in English at Christ Church, Oxford. His writing continued and he published a series of novels under his own name, along with short stories and some major academic contributions, including a major section on modern writers for the

Oxford History of English Literature

.

Whilst not wanting to leave his beloved Oxford permanently, he managed to fit in to his busy schedule a visiting Professorship at the University of Washington and was also honoured by other Universities in the UK.

His wife Margaret, whom he had met and married whilst at Leeds in 1932, had practised medicine in Australia and later in Oxford, died in 1979. They had five children, one of whom (Angus) is also a writer. Stewart himself died in November 1994 in a nursing home in Surrey.

It was soon apparent that Pluckrose had been murdered. A brief inspection of the corpse suggested that the only other possibility was what lawyers call an Act of God – and that of the kind which patently violates Natural Law. Of those concerned perhaps only Professor Prisk considered the fatality so felicitous as to make this explanation plausible. And yet between Prisk and Pluckrose there was, so far as was generally known, no deep-seated occasion of malice. Simply, these two had been required to share a telephone. Such are the antipathies of the cloister.

Not that the place was in fact cloistered in any substantial sense. The provincial universities of England, although often abundantly medieval in point of architectural inconvenience, have little of the organization characteristic of traditional places of learning. The staff – a word which at Oxford or Cambridge might be used of persons employed in a hotel – is not accommodated in spacious common rooms and cosy suites. Sometimes it is provided with a cellar in which the extravagant may drink coffee-essence at eleven o’clock; sometimes there is also an attic with chairs, where meetings may be held; a midday meal is obtainable by those who will grab from a counter with one hand and from a cutlery basket with the other. The scholars live in remote suburbs, often surrounded by two, three, or even four children and a wife; they ‘come in’ three times a week (giving it out to be four) or four times a week (giving it out to be five). To warm the sombre private rooms with which they are provided small gas stoves are supplied; but lurking caretakers pounce with an extinguishing hand upon these should a few minutes’ absence justify the economy; nor has the sternly pencilled notice

Don’t touch the stove!

ever been known to restrain such cold and flint-hearted janitors. In short, the amenities of communal life are scanty, and perhaps the professors and lecturers are expected to go much out and acquaint themselves with the world. Unfortunately neither Pluckrose nor Prisk nor many of their colleagues has list or talent for this; for them the Scholar, as for Chaucer the Monk, is of little estimation without his right professional seclusion. But although they cannot bring with them from Oxford and Cambridge the immemorial organization of a learned community, they can and often do bring the somewhat attenuated charities which such societies produce. The matter of the telephone had rankled, as it might not have done in a larger air.

The death of Pluckrose, a beguilement from the first, was presently a sensation. Everybody was scared and shocked; everybody was literate; the result was a lavish expenditure of that sort of wit by which – psychologists assure us – the bewildered mind endeavours to maintain a perilous equilibrium. ‘

Gather the rose

,’ murmured young Roger Pinnegar as he swept gowned down windy corridors; ‘

gather the rose of love

.’ And ‘

Gather the rose of love while yet is time

,’ he said aloud to Mr Marlow under the great clock; ‘

Gather the rose of love while yet is time while loving thou

mayst

loved be with equal crime

.’ ‘

Vivez,

’ said Mr Marlow readily; ‘

vivez si m’en croyez

,

n’attendez à

demain

,

cueillez dès aujourd’hui les roses de la vie

. ’

‘Mitte

,’ said old Tavender, popping out of the Classics lecture room; ‘

mitte sectari rosa quo locorum sera moretur

.’ All three academic gentlemen giggled – Marlow and Pinnegar the more loudly in that their Latin was uncertain. ‘And I stick by that,’ said Tavender, waving his hand in what was presumably the direction of Quintus Horatius Flaccus. ‘Chuck it. Leave it alone. Forget about it. He’s horribly dead. Well, let it go at that.’

‘Go, lovely rose,’ said Pinnegar automatically.

‘Pluckrose is in his grave,’ said Marlow.

‘Professor Pluckrose Pounded to Pot-pourri,’ said Pinnegar.

‘Deceased Savant Smells Sweet,’ said Marlow. ‘Dead Biochemist Blossoms in Dust.’

‘Pounded?’ asked Tavender, lowering his voice;

‘really

pot-pourried?’

‘Absolutely so.’ Pinnegar nodded almost soberly. ‘And by the Martians. There’s the rub. By an inhabitant of earth – yes. Why not? Pluckrose was like that. But the Martians, so inappropriately named –’

‘Lucus’

, said Tavender, ‘

a non lucendo

.’

‘–the Martians, stolid and phlegmatic by their dull canals: why should they take to pounding Pluckrose with their planetary artillery? Ask Orson Welles.’

‘When you come to think of it,’ said Tavender, ‘Pluckrose was pretty close. What did one know of him. Not much.’

Pinnegar nodded. ‘Most secret and inviolate Pluckrose. Did he keep a mistress? Was he quietly devoted to a mother of incredible age? Had he formed a curious private collection of–’

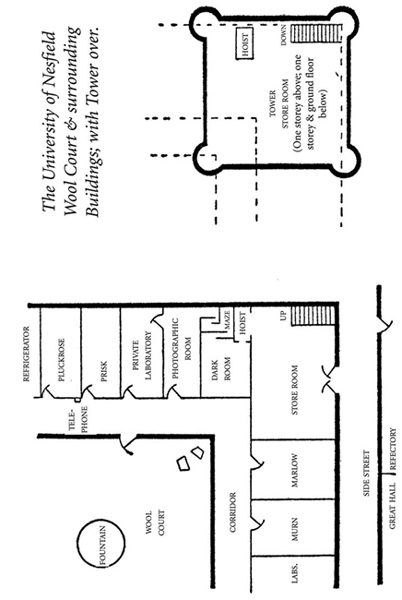

An electric bell of ingeniously piercing quality shrilled overhead. Doors banged. Students filled the corridors. Girls hurried past, bespectacled, note-booked, serious; girls loitered past, nudging, giggling, powdering; men skylarked, shouted, bit into sandwiches. Down the five ill-disposed wings of Nesfield University, vaulted, machine-carved, echoing, and damp, surged conflicting columns of adolescent humanity, a rout of jostling automotive sponges hurried from pool to pool of a knowledge codified, timetabled, and approved. Islanded in the midst, like three jackdaws among a charm of lesser fowls, Tavender, Marlow, and Pinnegar maintained their own characteristic and esoteric jabber. Outside, in a little plot of ground known as the Wool Court, Pluckrose, pounded and pashed, lay with a tarpaulin between him and a smeared and smoky sky.

‘A couple of years ago I had to do with a university murder,’ said Appleby. ‘But that was in the south. Oxford, was it – or Cambridge? I forget. So many of these things happen.’

‘Umph,’ said Inspector Hobhouse. The sound indicated that for him the humour of New Scotland Yard was without appeal.