The Wench is Dead (18 page)

Authors: Colin Dexter

‘Well, that’s it! I’ll put it in the post tonight, so you should—’

‘Can’t you call round, and bring it?’

‘Life’s, well, it’s just a bit hectic at the minute,’ she replied, after a little, awkward silence.

‘All right!’ Morse needed no further excuses. Having dipped the thermometer into the water, he’d found the reading a little too cold for any prospect of mixed bathing.

‘You see,’ said Christine, ‘I – I’m living with someone—’

‘And he doesn’t think you should go spending all your time helping me.’

‘I kept talking about you, too,’ she said quietly.

Morse said nothing.

‘Is your address the same as in the telephone directory? E. Morse?’

‘That’s me! That is I, if you prefer it.’

‘What does the “E” stand for? I never knew what to call you.’

‘They just call me “Morse”.’

‘You won’t forget me?’ she asked, after a little pause.

‘I’ll try to, I suppose.’

Morse thought of her for many minutes after he had cradled the phone. Then he recalled the testimony of Samuel Carter, and marvelled that a researcher of Carter’s undoubted experience and

integrity could make so many factual errors in the course of three or four pages: the date of the murder; Towns’ accent; Towns’ age; Wootton’s Christian name; the dropping of the

rape charge … Very interesting, though. Why, Morse had even guessed right about that dust-up with the knife! Well, almost right: he’d got the wrong man, but …

HAPTER

T

HIRTY-ONE

The second coastline is turned towards Spain and the west, and off it lies the island of Hibernia, which according to estimates is only half the size of Britain

(

Julius Caesar

, de Bello Gallico –

on the geography of Ireland

)

T

EN MINUTES LATER

the phone rang again, and Morse knew in his bones that it was Christine Greenaway.

It was Strange.

‘You’re out then, Morse – yes? That’s good. You’ve had a bit of a rough ride, they tell me.’

‘On the mend now, sir. Kind of you to ring.’

‘No

great

rush, you know – about getting back, I mean. We’re a bit understaffed at the minute, but give yourself a few days – to get over things. Delicate thing,

the stomach, you know. Why don’t you try to get away somewhere for a couple of days – new surroundings – four-star hotel? You can afford it, Morse.’

‘Thank you, sir. By the way, they’ve signed me off for a fortnight – at the hospital.’

‘Fortnight? A

fort

-night?’

‘It’s, er, a delicate thing, the stomach, sir.’

‘Yes, well …’

‘I’ll be back as soon as I can, sir. And perhaps it wouldn’t do me any harm to take your advice – about getting away for a little while.’

‘Do you a world of good! The wife’s brother’ (Morse groaned inwardly) ‘he’s just back from a wonderful holiday. Ireland – Southern Ireland – took the

car – Fishguard–Dun Laoghaire – then the west coast – you know, Cork, Kerry, Killarney, Connemara – marvellous, he said. Said you couldn’t have spotted a

terrorist with a telescope!’

It

had

been kind of Strange to ring; and as he sat in his armchair Morse reached idly for the World Atlas from his ‘large-book’ shelf, in which Ireland was a

lozenge shape of green and yellow on page 10 – a country which Morse had never really contemplated before. Although spelling errors would invariably provoke his wrath, he confessed to himself

that he could never have managed ‘Dun Laoghaire’, even with a score of attempts. And where was Kerry? Ah yes! Over there, west of Tralee – he was on the right bit of the map

– and he moved his finger up the coast to Galway Bay. Then he saw it: Bertnaghboy Bay! And suddenly the thought of going over to Connemara seemed overwhelmingly attractive. By himself? Yes,

it probably had to be by himself; and he didn’t mind that, really. He was somewhat of a loner by temperament – because though never wholly happy when alone he was usually slightly more

miserable when with other people. It would have been good to have taken Christine, but … and for a few minutes Morse’s thoughts travelled back to Ward 7C. He would send a card to Eileen

and Fiona; and one to ‘Waggie’ Greenaway, perhaps? Yes, that would be a nice gesture: Waggie had been out in the wash-room when Morse had left, and he’d been a pleasant

old—

Suddenly Morse was conscious of the tingling excitement in the nape of his neck, and then in his shoulders. His eyes dilated and sparkled as if some inner current had been activated; and he sat

back in the armchair and smiled slowly to himself.

What, he wondered, was the routine in the Irish Republic for

exhumation

?

HAPTER

T

HIRTY-TWO

Oh what a tangled web we weave

When first we practise to deceive!

(

Sir Walter Scott

, Marmion)

‘Y

OU

WHAT

?’ asked a flabbergasted Lewis, who had called round at 7.30 p.m. (‘Not till

The Archers

has finished’

had been his strict instruction.) He himself had made an interesting little discovery – well, the WPC in St Aldates’ had made it, really – and he was hoping that it might amuse

Morse in his wholly inconsequential game of ‘Find Joanna Franks’. But to witness Morse galloping ahead of the Hunt, chasing (as Lewis was fairly certain) after some imaginary fox of his

own, was, if not particularly unusual, just a little disconcerting.

‘You see, Lewis’ (Morse was straightway in full swing) ‘this is one of the most beautiful little deceptions we’ve ever come across. The

problems

inherent in the

case – almost all of them – are resolved immediately once we take one further step into imaginative improbability.’

‘You’ve lost me already, sir,’ protested Lewis.

‘No, I haven’t! Just take one more step

yourself

. You think you’re in the

dark

? Right? But the dark is where we

all

are. The dark is where

I

was,

until I took one more step into the dark. And then, when I’d taken it, I found myself in the

sunshine

.’

‘I’m very glad to hear it,’ mumbled Lewis.

‘It’s like this. Once I read that story, I was uneasy about it – doubtful, uncomfortable. It was the

identification

bit that worried me – and it would have worried

any officer in the Force today,

you

know that! But, more significantly, if we consider the psychology of the whole—’

‘Sir!’ (It was almost unprecedented for Lewis to interrupt the Chief in such peremptory fashion.) ‘Could we – could you – please forget all this psychological

referencing? I just about get my fill of it all from some of these Social Services people. Could you just tell me, simply and—’

‘I’m boring you – is that what you’re saying?’

‘

Exactly

what I’m saying, sir.’

Morse nodded to himself happily. ‘Let’s put it

simply

, then, all right? I read a story in hospital. I get interested. I think –

think

– the wrong people got

arrested, and some of ’em hanged, for the murder of that little tart from Liverpool. As I say, I thought the identification of that lady was a bit questionable; and when I read the words the

boatmen were alleged to have used about her – well, I knew there must be something fundamentally

wrong

. You see—’

‘You said you’d get to the point, sir.’

‘I thought that Joanna’s father – No! Let’s start again! Joanna’s father gets a job as an insurance rep. Like most people in that position he gets a few of his own

family, if they’re daft enough, to take out a policy with him. He gets a bit of commission, and he’s not selling a phoney product, anyway, is he? I think that both Joanna and her

first

husband, our conjurer friend, were soon enlisted in the ranks of the policy-holders. Then times get tough; and to crown all the misfortunes, Mr Donavan, the greatest man in all the

world, goes and dies. And when Joanna’s natural grief has abated – or evaporated, rather – she finds she’s done very-nicely-thank-you out of the insurance taken on his life.

She receives £100, with profits, on what had been a policy taken out only two or three years previously. Now, £100 plus in 1850-whenever was a very considerable sum of money; and Joanna

perhaps began, at that point, to appreciate the potential for

malpractice

in the system. She began to see the insurance business not only as a potential

future

benefit, but as an

actual,

present

source of profit. So, after Donavan’s death, when she met and married Franks, one of the first things she insisted on was his taking out a policy – not on

his

life – but on

hers

. Her father could, and did, effect such a transaction without any trouble, although it was probably soon after this that the Notts and Midlands Friendly

Society got a little suspicious about Joanna’s father, Carrick – Daniel Carrick – and told him his services were no longer—’

‘Sir!’

Morse held up his right hand. ‘Joanna Franks was

never

murdered, Lewis! She was the mastermind – mistressmind – behind a deception that was going to rake in some

considerable, and desperately needed, profit. It was

another

woman, roughly the same age and the same height, who was found in the Oxford Canal; a woman provided by Joanna’s

second

husband, the ostler from the Edgware Road, who had already made his journey – not difficult for

him

! – with horse and carriage from London, to join his wife at

Oxford. Or, to be more accurate, Lewis, at some few points

north

of Oxford. You remember in the Colonel’s book?’ (Morse turned to the passage he had in mind.) ‘He –

here it is! – “he explained how in consequence of some information he had come into Oxfordshire” – Bloody liar!’

Lewis, now interested despite himself, nodded a vague concurrence of thought. ‘So what you’re saying, sir, is that Joanna worked this insurance fiddle and probably made quite a nice

little packet for herself and for her father as well?’

‘Yes! But not only that. Listen! I may just be wrong, Lewis, but I think that not only was Joanna wrongly identified as the lawful wife of Charles Franks – by Charles Franks –

but that Charles Franks was the

only

husband of the woman supposedly murdered on the

Barbara Bray

. In short, the “Charles Franks” who broke down in tears at the second

trial was

none other than Donavan

.’

‘Phew!’

‘A man of many parts: he was an actor, he was a conjurer, he was an impersonator, he was a swindler, he was a cunning schemer, he was a callous murderer, he was a loving husband, he was a

tearful witness, he was the first and

only

husband of Joanna Franks: F. T. Donavan! We all thought – you thought – even

I

thought – that there were three principal

characters playing their roles in our little drama; and now I’m telling you, Lewis, that in all probability we’ve only got

two

. Joanna; and her husband – the greatest man

in all the world; the man buried out on the west coast of Ireland, where the breakers come rolling in from the Atlantic … so they tell me …’

HAPTER

T

HIRTY-THREE

Stet Difficilior Lectio

(Let the more difficult of the readings stand)

(

The principle applied commonly by editors faced with

variant readings in ancient manuscripts

)

L

EWIS WAS SILENT

. How else? He had a precious little piece of evidence in his pocket, but while Morse’s mind was still coursing through the upper

atmosphere, there was little point in interrupting again for the minute. He put the envelope containing the single photocopied sheet on the coffee-table – and listened further.

‘In the account of Joanna’s last few days, we’ve got some evidence that she could have been a bit deranged; and part of the evidence for such a possibility is the fact that at

some point she kept calling out her husband’s name – “Franks! Franks! Franks!” Agreed? But she

wasn’t

calling out that at all – she was calling her

first

husband, Lewis! I was sitting here thinking of “Waggie” Greenaway—’

‘And his daughter,’ mumbled Lewis, inaudibly.

‘—and I thought of “Hefty” Donavan. F. T. Donavan. And I’ll put my next month’s salary on that “F” standing for “Frank”! Huh!

Who’s ever heard of a wife calling her husband by his surname?’

‘I have, sir.’

‘Nonsense! Not these days.’

‘But it’s

not

these days. It was—’

‘She was calling

Frank Donavan

– believe me!’

‘But she

could

have been queer in the head, and if so—’

‘Nonsense!’

‘Well, we shan’t ever know for sure, shall we, sir?’

‘Nonsense!’

Morse sat back with the self-satisfied, authoritative air of a man who believes that what he has called ‘nonsense’ three times must, by the laws of the universe, be necessarily

untrue. ‘If

only

we knew how tall they were – Joanna and … and whoever the other woman was. But there

is

just a chance, isn’t there? That cemetery,

Lewis—’

‘Which do you want first, sir? The good news or the bad news?’

Morse frowned at him. ‘That’s …?’ pointing to the envelope.

‘That’s the good news.’

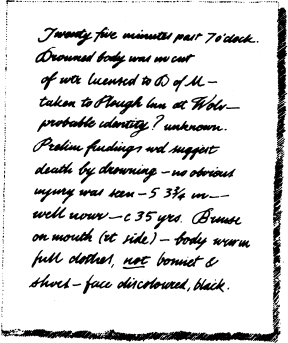

Morse slowly withdrew and studied the photocopied sheet.