The Wench is Dead (19 page)

Authors: Colin Dexter

‘Not the Coroner’s Report, sir, but the next best thing. This fellow must have seen her before the

post-mortem

. Interesting, isn’t it?’

‘

Very

interesting.’

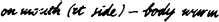

The report was set out on an unruled sheet of paper, dated, and subscribed by what appeared as a ‘Dr Willis’, for the writing was not only fairly typical of the semi-legibility

forever associated with the medical profession, but was also beset by a confusion with ‘m’s, ‘w’s, ‘n’s, and ‘u’s – all these letters appearing

to be incised with a series of what looked like semi-circular fish-hooks. Clearly the notes of an orderly-minded local doctor called upon to certify death and to take the necessary action –

in this case, almost certainly, to pass the whole business over to some higher authority. Yet there were one or two real nuggets of gold here: the good Willis had made an exact measurement of

height, and had written one or two most pertinent (and, apparently, correct) observations. Sad, however, from Morse’s point of view, was the unequivocal assertion made here that

the body

was still warm

. It must have been this document which had been incorporated into the subsequent

post-mortem

findings, thenceforth duly reiterated both in Court and in the Colonel’s

history. And it

was

a pity; for if Morse had been correct in believing that another body had been substituted for that of Joanna Franks, that woman must surely have been killed in the early

hours of the morning, and could

not

therefore have been drowned some three or four hours later.

Far

too risky. It was odd, certainly, that the dead woman’s face had turned black

so very quickly; but there was no escaping the plain fact that the first medical man who had examined the corpse had found it still

warm

.

Is that what the report had said, though – ‘still warm’? No! No, it hadn’t! It just said ‘warm’ … Or

did

it?

Carefully Morse looked again at the report – and sensed the old familiar tingling around his shoulders.

Could

it be? Had everyone else read the report wrongly? In every case the

various notes were separated from each other by some form of punctuation – either dashes (eight of them) or full stops (four) or question-marks (only one). All the notes

except

one,

that is: the exception being that ‘body warm/full clothes …’ etc. There was neither a dash nor a stop between these two, clearly disparate, items – unless the photocopier had

borne unfaithful witness. No! The solution was far simpler. There had been no break requiring any punctuation! Morse looked again at line 10 of the report,

and considered three further facts. Throughout, the ‘s’s were written almost as straight vertical lines; of the fifteen or so ‘i’ dots, no fewer than six

had remained un-dotted; and on this showing Willis seemed particularly fond of the word ‘was’. So the line should perhaps – should certainly! – read as follows: ‘on

mouth (rt side) – body was in’. The body ‘was in full clothes’! The body was

not

‘warm’; not in Morse’s book. There, suddenly, the body was very,

very cold.

Lewis, whilst fully accepting the probability of the alternative reading, did not appear to share the excitement which was now visibly affecting Morse; and it was time for the bad news.

‘No chance of checking this out in the old Summertown graveyard, sir.’

‘Why not? The gravestones are still there, some of them – it says so, doesn’t it? – and I’ve seen them myself—’

‘They were all removed, when they built the flats there.’

‘Even those the Colonel mentioned?’

Lewis nodded.

Morse knew full well, of course, that any chance of getting an exhumation order to dig up a corner of the greenery in a retirement-home garden was extremely remote. Yet the thought that he might

have clinched his theory … It was not a matter of supreme moment, though, he knew that; it wasn’t even important in putting to rights a past and grievous injustice. It was of no great

matter to anyone – except to himself. Ever since he had first come into contact with problems, from his early schooldays onwards – with the meanings of words, with algebra, with

detective stories, with cryptic clues – he had always been desperately anxious to know the

answers

, whether those answers were wholly satisfactory or whether they were not. And now,

whatever had been the motive leading to that far-off murder, he found himself irked in the extreme to realize that the woman – or

a

woman – he sought had until so very recently

been lying in a marked grave in North Oxford. Had she been Joanna Franks, after all? No chance of knowing now – not for certain. But if the meticulous Dr Willis had been correct in his

measurements, she

couldn’t

have been Joanna, surely?

After Lewis had gone, Morse made a phone call.

‘What was the average height of women in the nineteenth century?’

‘Which end of the nineteenth century, Morse?’

‘Let’s say the middle.’

‘Interesting question!’

‘Well?’

‘It varied, I suppose.’

‘Come

on!’

‘Poor food, lack of protein – all that sort of stuff. Not very big, most of ’em. Certainly no bigger than the Ripper’s victims in the 1880s: four foot nine, four foot ten, four

foot eleven – that sort of height: well, that’s about what

those

dear ladies were. Except one. Stride, wasn’t her name? Yes, Liz Stride. They called her “Long Liz” –

so much taller than all the other women in the work-houses. You follow that, Morse?’

‘How tall was

she –

“Long Liz”?’

‘Dunno.’

‘Can you find out?’

‘What, now?’

‘And ring me back?’

‘Bloody hell!’

‘Thanks.’

Morse was three minutes into the love duet from Act One of

Die Walküre

when the phone rang.

‘Morse? Five foot three.’

Morse whistled.

‘Pardon?’

‘Thanks, Max! By the way, are you at the lab all day tomorrow? Something I want to bring to show you.’

So the ‘petite’ little figure had measured three quarters of an inch

more

than ‘Long Liz’ Stride! And her shoes as Lewis had ascertained, were about size 5! Well,

well, well! Virtually every fact now being unearthed (though that was probably not

le mot juste

) was bolstering Morse’s bold hypothesis. But, infuriatingly, there was, as it seemed, no

chance whatever of establishing the truth. Not, at any rate, the truth regarding Joanna Franks.

HAPTER

T

HIRTY-FOUR

Marauding louts have shot the moping owl:

The tower is silent ’neath the wat’ry moon;

But Lady Porter, lately on the prowl

Will sell the place for pennies very soon

(

E. O. Parrot

, The Spectator)

T

HE COMMUNICATION FROM

the Insurance Company had been a third and final demand for his previous month’s premium; and the first thing Morse did the

following morning was to write out a cheque, with a brief letter of apology. He understood very little about money, but a dozen or so years previously he had deemed it provident (as it transpired,

Prudential) to pay a monthly premium of £55 against a lump sum of £12,000, with profits, at sixty – an age looming ever closer. He had never given a thought about what would

happen if he pre-deceased his policy. No worry for him: for the present he had no financial worries, no dependants, a good salary, and a mortgage that would finish in two years’ time. He knew

it, yes! – compared with the vast majority of mankind he was extremely fortunate. Still, he ought perhaps to think of making a will …

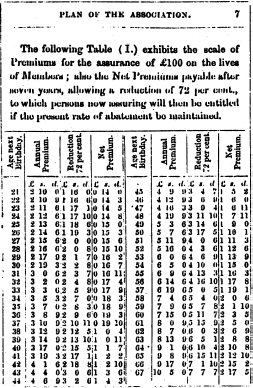

Coincidentally, he had been talking to Lewis about insurances the day before and (he admitted it to himself) largely making it all up as he went along. But it was

far

from improbable,

wasn’t it – what he’d guessed? Those insurance fiddles? He looked out the first material that Christine had brought in to him at the JR2, and once again studied the facts and

figures of the Nottinghamshire and Midlands Friendly Society for 1859:

Joanna had been born in 1821, so she was thirty-eight in 1859. If she’d taken out a policy a year, two years earlier, that would be – age next birthday thirty-six – an annual

premium of £3. 8

s

9

d

. Under £7, say, for a return of £100. Not bad at all. And if Donavan had already pocketed a similar packet …

Morse left his flat in mid-morning (the first excursion since his return) and posted his single letter. He met no one he knew as he turned right along the Banbury Road, and

then right again into Squitchey Lane; where, taking the second turning on his left, just past the evangelical chapel (now converted into a little group of residences) he walked down Middle Way. It

was a dark, dankish morning, and a scattering of rooks (mistaking, perhaps, the hour) squawked away in the trees to his right. Past Bishop Kirk Middle School he went on, and straight along past the

attractive terraced houses on either side with their mullioned bay-windows – and, on his left,

there it was

: Dudley Court, a block of flats built in cinnamon-coloured brick on the site

of the old Summertown Parish Cemetery. A rectangle of lawn, some fifty by twenty-five yards, was set out behind a low containing wall, only about eighteen inches high, over which Morse stepped into

the grassy plot planted with yew-trees and red-berried bushes. Immediately to his left, the area was bounded by the rear premises of a Social Club; and along this wall, beneath the straggly

branches of winter jasmine, and covered with damp beech-leaves, he could make out the stumps of four or five old headstones, broken off at their roots like so many jagged teeth just protruding from

their gums. Clearly, any deeper excavation to remove these stones in their entirety had been thwarted by the proximity of the wall; but all the rest had been removed, perhaps several years ago now

– and duly recorded no doubt in some dusty box of papers on the shelves of the local Diocesan Offices. Well, at least Morse could face one simple fact: no burial evidence would be forthcoming

from these fair lawns. None! Yet it would have been good to know where the stone had marked (as the Colonel had called it) the ‘supra-corporal’ site of Joanna Franks.

Or whoever.

He walked past Dudley Court itself where a Christmas tree, bedecked with red, green, and yellow bulbs, was already switched on; past the North Oxford Conservative Association premises, in which

he had never (and would never) set foot; past the Spiritualist Church, in which he had never (as yet) set foot; past the low-roofed Women’s Institute HQ, in which he had once spoken about the

virtues of the Neighbourhood Watch Scheme; and finally, turning left, he came into South Parade, just opposite the Post Office – into which he ventured once a year and that to pay the

Lancia’s road-tax. But as he walked by the old familiar landmarks, his mind was far away, and the decision firmly taken. If he was to be cheated of finding one of his suspects, he would go

and look for the other! He needed a break. He would

have

a break.

There was a travel agency immediately across the street, and the girl who sat at the first desk to the right smiled brightly.

‘Can I help you, sir?’

‘Yes! I’d like’ (Morse sat himself down) ‘I’d like to book a holiday, with a car, in Ireland – the Republic, that is.’

Later that day, Morse called at the William Dunn School of Pathology in South Parks Road.

‘Have a look at these for me, will you?’

Refraining from all cynical comment, Max looked dubiously across at Morse over his half-lenses.

‘Max! All I want to know is—’

‘—whether they come from M&S or Littlewoods?’

‘The tear, Max –

the tear

.’

‘Tear?

What

tear?’ Max picked up the knickers with some distaste and examined them (as it seemed to Morse) in cursory fashion. ‘No tear here, Morse. Not the faintest

sign of any irregular distension of the fibre tissue – calico, by the way, isn’t it?’

‘I think so.’