The White Goddess (13 page)

Authors: Robert Graves

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Mythology, #Literature, #20th Century, #Britain, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Mysticism, #Retail

H

ANES

B

LODEUWEDD

line 142

Not

of

father

nor

of

mother144

Was

my

blood,

was

my

body.156

I

was

spellbound

by

Gwydion,157

Prime

enchanter

of

the

Britons,143

When

he

formed

me

from

nine

blossoms

,149

Nine

buds

of

various

kind:148

From

primrose

of

the

mountain

,121

Broom,

meadow-sweet

and

cockle

,

Together

intertwined

,75

From

the

bean

in

its

shade

bearing76

A

white

spectral

army150

Of

earth,

of

earthly

kind

,152

From

blossoms

of

the

nettle

,129

Oak,

thorn,

and

bashful

chestnut

–[146

Nine

powers

of

nine

flowers,

145]

Nine

powers

in

me

combined,149

Nine

buds

of

plant

and

tree.220

Long

and

white

are

my

fingers153

As

the

ninth

wave

of

the

sea.

In Wales and Ireland primroses are reckoned fairy flowers and in English folk tradition represent wantonness (cf. ‘the primrose path of dalliance’ –

Hamlet

;

the ‘primrose of her wantonness’ – Brathwait’s

Golden

Fleece

)

.

So Milton’s ‘yellow-skirted fayes’ wore primrose. ‘Cockles’ are the ‘tares’ of the Parable that the Devil sowed in the wheat; and the bean is traditionally associated with ghosts – the Greek and Roman homoeopathic remedy against ghosts was to spit beans at them – and Pliny in his

Natural

History

records the belief that the souls of the dead reside in beans. According to the Scottish poet Montgomerie (1605), witches rode on bean-stalks to their sabbaths.

To return to the Battle of the Trees. Though the fern was reckoned a ‘tree’ by the Irish poets, the ‘plundered fern’ is probably a reference to fern-seed which makes invisible and confers other magical powers. The twice-repeated ‘privet’ is suspicious. The privet figures unimportantly in Irish poetic tree-lore; it is never regarded as ‘blessed’. Probably its second occurrence in line 100 is a disguise of the wild-apple, which is the tree most likely to smile from beside the rock, emblem of security: for Olwen, the laughing Aphrodite of Welsh legend, is always connected with the

wild-apple. In line 99 ‘his berries are thy dowry’ is absurdly juxtaposed to the hazel. Only two fruit-trees could be said to dower a bride in Gwion’s day: the churchyard yew whose berries fell at the church porch where marriages were always celebrated, and the churchyard rowan, often substituted for the yew in Wales. I think the yew is here intended; yew-berries were prized for their sticky sweetness. In the tenth-century Irish poem,

King

and

Hermit

,

Marvan the brother of King Guare of Connaught commends them highly as food.

The remaining stanzas of the poem may now be tentatively restored:

(lines 110, 160, and 161)

I

have

plundered

the

fern

,

Through

all

secrets

I

spy

,Old

Math

ap

Mathonwy

Knew

no

more

than

I.

(lines 101, 71–73, 77

and 78)Strong

chieftains

were

the

blackthorn

With

his

ill

fruit,

The

unbeloved

whitethorn

Who

wears

the

same

suit.

(lines 116, 111–113)

The

swift-pursuing

reed

,

The

broom

with

his

brood

,And

the

furze

but

ill-behaved

Until

he

is

subdued.

(lines 97, 99, 128, 141, 60)

The

dower-scattering

yew

Stood

glum

at

the

fight’s fringe,

With

the

elder

slow

to

burn

Amid

fires

that

singe

,(lines 100, 139 and 140)

And

the

blessed

wild

apple

Laughing

for

prideFrom

the

Gorchan

of Maelderw

,

By

the

rock

side.

(lines 83, 54, 25, 26)

But

I,

although

slighted

Because

I

was

not

big,Fought,

trees,

in

your

array

On

the

field

of Goddeu

Brig.

The broom may not seem a warlike tree, but in Gratius’s

Genistae

Altinates

the tall white broom is said to have been much used in ancient times for the staves of spears and darts: these are probably the ‘brood’.

Goddeu

Brig

means Tree-tops, which has puzzled critics who hold that

Câd

Goddeu

was a battle fought in Goddeu, ‘Trees’, the Welsh name for Shropshire. The

Gorchan

of Maelderw (‘the incantation of Maelderw’) was a long poem attributed to the sixth-century poet Taliesin, who is said to have particularly prescribed it as a classic to his bardic colleagues. The

apple-tree was a symbol of poetic immortality, which is why it is here presented as growing out of this incantation of Taliesin’s.

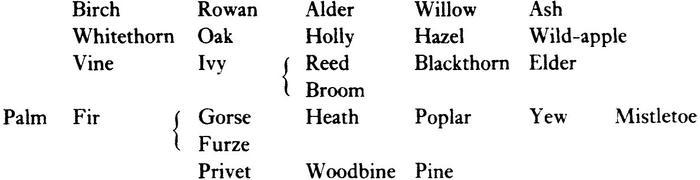

Here, to anticipate my argument by several chapters, is the Order of Battle in the

Câd

Goddeu

:

It should be added that in the original, between the lines numbered 60 and 61, occur eight lines unintelligible to D. W. Nash: beginning with ‘the chieftains are falling’ and ending with ‘blood of men up to the buttocks’. They may or may not belong to the

Battle

of

the

Trees.

I leave the other pieces included in this medley to be sorted out by someone else. Besides the monologues of Blodeuwedd, Hu Gadarn and Apollo, there is a satire on monkish theologians, who sit in a circle gloomily enjoying themselves with prophecies of the imminent Day of Judgement (lines 62–66), the black darkness, the shaking of the mountain, the purifying furnace (lines 131–134), damning men’s souls by the hundred (lines 39–40) and pondering the absurd problems of the Schoolmen:

(lines 204, 205)

Room

for

a

million

angels

On

my

knife-point,

it

appears.(lines 167 and 176)

Then

room

for

how

many

worlds

A-top

of

two

blunt

spears?

This introduces a boast of Gwion’s own learning:

(lines 201,200)

But

I

prophesy

no

evil

,

My

cassock

is

wholly

red.(line 184)

‘He

knows

the

Nine

Hundred

Tales

’ –

Of

whom

but

me

is

it

said?