Theory of Fun for Game Design (14 page)

Read Theory of Fun for Game Design Online

Authors: Raph Koster

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Programming / Games

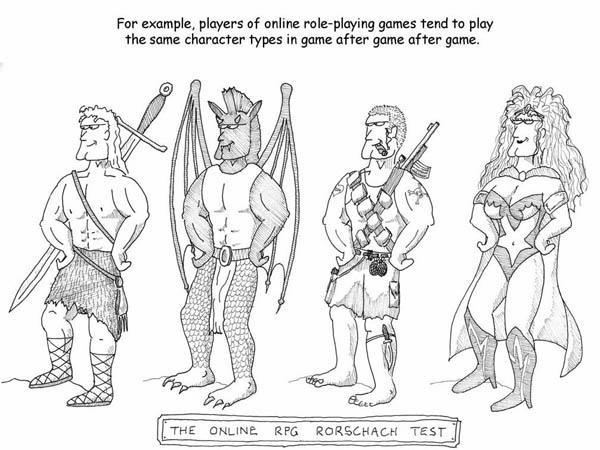

Another case where the wiring of the human brain tends to betray us lies in the seductive feeling of make-believe mastery.

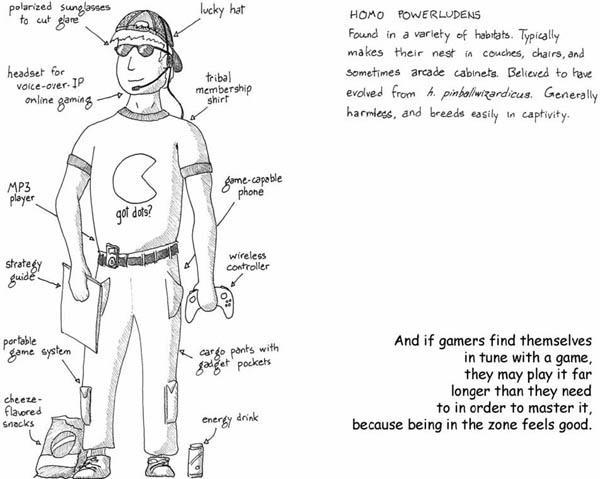

Engaging in an activity that you have fully mastered, being in the zone, feeling the flow, can be a heady experience. And no one can deny the positive effects of meditation. That said, the point at which a player chooses to repeatedly play a game they have already mastered completely, just because they like to feel powerful, is the point at which the game is betraying its own purpose. Games need to encourage you to

move on

. They are not there to fulfill power fantasies.

Ah, but is it seductive! Because games exist within the confines of “let’s pretend,” they also offer a lack of consequences. They are libertine in their freedoms. They let you be a godlet. To the person that perhaps does not get enough sense of control in their real lives, the game may offer something rather…persuasive.

Making you feel good about yourself in a pretend arena isn’t what games are for. Games are for offering challenges, so that you can then turn around and apply those techniques to real problems. Going back through defeated challenges in order to pass time isn’t a productive exercise of your brain’s abilities. Nonetheless, lots of people do it.

Some choose to play for “style points,” which is at least a sign that they are creating new challenges for themselves. But once you get past the point of doing something perfectly, do yourself a favor and

quit the game

.

There are other sorts of audience problems with games. One of them has proven fatal to many genres of games: the problem of increasing complexity. Most art forms have swung in pendulum fashion from an Apollonian to a Dionysian style—meaning, they have alternated between periods where they were reserved and formal and where they were exuberant and communicative. From Romanesque to Gothic churches, from art rock to punk, from the French Academy to Impressionism, pretty much every medium has had these swings.

Games, however, are always formal. The historical trend in games has shown that when a new genre of game is invented, it follows a trajectory where increasing complexity is added to it, until eventually the games on the market are so complex and advanced that newcomers can’t get into them—the barrier of entry is too high. You could call this the jargon factor because it is common to

all

formal systems. Priesthoods develop, terms enter common usage, and soon only the educated few can hack it.

In most media, the way out of this has been the development of a new formal principle (as well as a cultural shift). Sometimes it was a development in knowledge of the form. Sometimes it was the development of a competing medium that usurped the place of the old medium, as when photography forced painters to undergo a radical reevaluation of their art form. Games, though, aren’t tending to do this all that much. By and large, we have seen an inexorable march toward greater complexity. This has led to a priesthood of those who can speak the language, master the intricacies, and keep up-to-date.

Every once in a while games come along that appeal to the masses, and thank goodness. Because frankly, priesthoods are a perversion of what games are about as well. The worst possible fate for games (and by extension, for our species) would be for games to become niche, something played by only a few elite who have the training to do so. It was bad for sports, it was bad for music, it was bad for writing, and it would be bad for games as well.

Conversely, it’s possible that instead games are like the Twonky from the famous science fiction story. Maybe the kids will keep up, and the older people won’t be able to. And then we’ll get left behind…

All of these are cases where human nature works against the success of games as a medium and as a teaching tool. Ironically, these all converge most sharply in the most unlikely of candidates, the person who loves games more than anyone: the game designer.

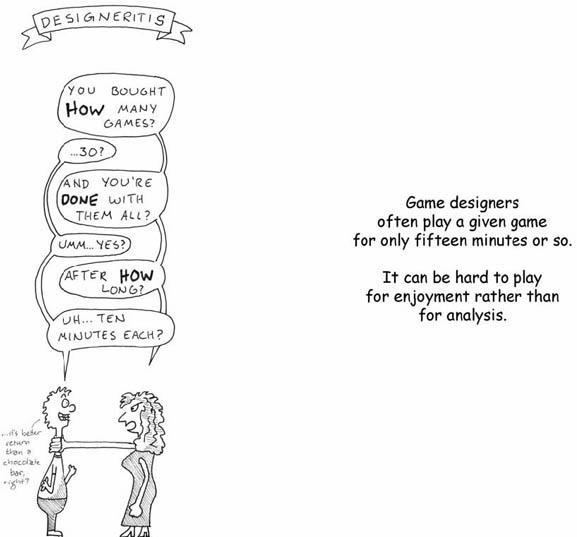

Game designers spend less time playing individual games than the typical player does. Game designers finish games less often than typical players do. They have less time to play a given game because they typically sample so many of them. And perniciously, they are just as likely, if not more so because of business pressures, to turn to known solutions.

Basically, game designers suffer from what I call “designeritis.” They are hypersensitive to patterns in games. They grok them very readily and move on. They see past fiction very easily. They build up encyclopedic recollections of games past and present, and they then theoretically use these to make new games.

But they usually

don’t

make new games because their very experience, their very library of assumptions, holds them back. Remember what the brain is doing with these chunks it builds—it is trying to create a generically applicable library of solutions. The more solutions you have stored up, the less likely you are to go chasing after a new one.

The result has been, as you would expect, a lot of derivative work. Yes, you need to know the rules in order to break them, but given the lack of codification and critique of what games are, game designers have instead operated under the more guildlike model of apprenticeship. They do what they have seen work.

The most creative and fertile game designers working today tend to be the ones who make a point of

not

focusing too much on other games for inspiration. Creativity comes from cross-pollination, not the reiteration of the same ideas. By making gaming their hobby, game designers are making an echo chamber of their own work. Because of this, it is critical that games be placed in context with the rest of human endeavor so that game designers can feel comfortable venturing outside their field in search of innovative ideas.

Game designers are doing something that really isn’t their job—they are evolving game design into a discipline. And it’s a good thing that they are doing it. This has been happening slowly over the past few decades and particularly in the past 10 years.

I don’t necessarily mean they are becoming all scientific about it. But we have seen the following: a large increase in the number of books about game design, the beginnings of a critical vocabulary, and the creation of academic programs that attempt to engage in critique. In short, the field has started to move away from the hit-and-miss shots-in-the-dark approach and toward an understanding of what games are and how they work. This is an important final step in the maturation process of a medium.

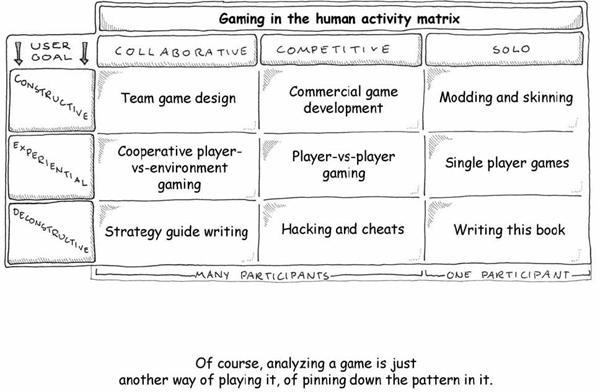

On the facing pages where you usually see what are hopefully amusing cartoons, I’ve filled out a few grids with different human endeavors. Bear with me—there are two sorts of people in this world, those who divide everyone into two sorts of people and those who don’t.

Any given activity can be performed either by yourself or with others. If you are doing it with others, you can be working either with or against each other. I call these three approaches

collaborative, competitive

, and

solo

.

Down the side of our grid, I’ve made a subtler distinction. Are you a passive consumer of this activity? An audience member? Or do you actively work on the activity? If you are someone who doesn’t work on the activity but instead lets the work of others wash over you, we’ll call you interested in the

experiential

side of the activity—you want the experience.

Are you actually

creating

the experience? Then you are engaging in a

constructive

activity. Maybe instead, you are taking the experience apart, to see how it works. I used to label this destructive, but it’s not really; often the original is left behind, intact though somewhat bruised and battered. So perhaps

deconstructive

is a better term.

My second grid shows how we can analyze music. When I look at the chart for music, what I see is a constellation of music-based entertainment. If I made a similar chart for books, it would cover prose-based entertainment. Basically, this chart can be applied to any

medium

.

“Game” is not a medium, even though I have misused it that way on almost every page of this book. It is, depending on the definition, one

use

of a medium. The medium is really an unwieldy phrase like “formal abstract models for teaching patterns.” And once you see that, you see that even though fire drills or CIA model war games of the future of the Middle East may not necessarily be fun, they still belong on the chart. The fact that they are not fun has more to do with their implementation than with their intrinsic nature.

Interaction is possible in all media. Interacting with stage-based media is termed “acting” and interacting with prose-based media is termed “writing.” There’s been a lot of discussion in professional video game design circles lately about “the surrender of authorship” inherent in adding greater flexibility to games and in the burgeoning “mod” community. I think the key insight here is that players are simply “interacting with the medium.”